INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The work of the World Economic Forum and its Partners on sustainable consumption rests on a set of simple, but vital, premises about the systemic nature of the sustainability challenge, and the actions needed to address it:

- Driving sustainable consumption is about more than corporate social responsibility; it is about necessary fundamental changes in the way business is done and the way the world consumes, requiring rethinking of business models, supply chains and how society values goods and services.

- It is about fundamental changes in the way businesses survive and thrive in ten years time - about deep and broad engagement between business and other stakeholders, within and across value chains and industries.

- It is about enabling an expanding global population to consume sustainably, changing consumption patterns in the developed world while creating a model for long-term prosperity in the developing world.

- It requires a step-change in ambitions for the impact that business and consumption have on the human and natural environment, from "less bad" to "actively good".

- Finally, while realizing ambitions for sustainable consumption will be challenging and take time, the process involves myriad opportunities for business innovation, profit and leadership. That process has already begun; the foundations for a wider economic transformation have already been laid.

Building on the rationale for business engagement, as laid out in The Business Case for Sustainability in January 2009, this report explores the core elements of a long-term vision for sustainable consumption. The objective of this report is to offer immediate, practical ideas on how companies can partner across industry boundaries to begin to realize that vision now, as developed in section 5 of this report.1 As this document is written to facilitate discussions at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2010 in Davos-Klosters, we hope that the challenges and opportunities presented here will catalyse specific and practical partnerships, to be carried forward by Partner companies through 2010 and beyond.

The Project Board of 15 companies identified three specific areas as offering the best opportunities to generate new insights and catalyse new partnerships. Three working groups were convened, on building closed loop systems, eliminating value-chain waste and advancing consumer engagement, with workshops led by Nike, Nestlé and Unilever respectively.

The process of aggregating and then distilling current global experience and expertise builds on a series of meetings and workshops held in Brazil, People's Republic of China, Denmark, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States, complemented by interviews and additional research. Throughout the process, over 100 businesses and 250 individuals from business, the public sector and academia have been involved. Along the way, the process has been enriched by valuable contributions from the World Economic Forum's Global Agenda Council on Sustainable Consumption. Special thanks are due to Deloitte, which is supporting this work as project adviser for a second year.

The work of the Forum and its Partners on sustainable consumption offers a powerful example of Corporate Global Citizenship in action and makes clear that finding solutions to today's key global societal challenges requires the collaboration of business, government, and civil society.

|

Robert Greenhill |

Sarita Nayyar |

CEO FOREWORD

The World Is At A Tipping Point.

Populations are rising. The availability of natural resources is diminishing. Global economic health is based on consumption. Without fundamental changes, our global economy is at risk.

A prosperous future depends on innovative new products and business models that achieve transformative efficiency – and create new market opportunities.

This transformation will be significantly driven by companies, in part through public-private cooperation and partnerships. Tomorrow's businesses will meet the future by channelling their creativity to form markets that capture the emerging opportunities these shifts offer.

Every period of disruptive change brings winners and losers. The formula for business success during our era of great change will place a premium on innovation, collaboration and smart investments to shape a globally prosperous and sustainable future.

To build a future of sustainable consumption, we need:

- Innovation: Sustainability is an enabler of innovation and should be at the core of the design of products and services and the development of new business models and platforms.

- Collaboration: New forms of collaboration between business partners, along entire value chains, and with key stakeholder groups will be needed.

- Investment: To catalyse a prosperous future, business needs to look beyond short-term pressures and focus on investment for the long term, working to build understanding among investors of the value at stake in long-term planning.

- Values: To become relevant in shaping a better future for society, new values-based frameworks are needed to align behaviour in more productive and innovative ways.

- Leadership: As business leaders, we choose to lead from the front, because we see that the cost of inaction to our businesses far outweighs the cost of action.

We believe we have the potential to create new business models that build lasting prosperity for the many and not for the few; that make wise use of natural resources; that internalize social and environmental capital; and that focus on innovation to thrive in a low-carbon, dematerialized economy driving smarter consumption.

In addition to our individual commitments to sustainability, we seek collectively to leverage the platform offered by the World Economic Forum to explore and develop practical collaborations around key actionable partnerships.

Within this report are many specific and sensible ideas to ground these aspirations in opportunity for action. Commitment to these principles and actions will set the foundation for transformational change. We see a tremendous challenge ahead, and success should not be celebrated before progress can be measured and results are shown.

But we also see a great opportunity. If you are reading this foreword, then read on and join the action.

|

Leo Apotheker |

Carl Bass |

Paul Bulcke |

|

Brian Dunn |

Richard W. Edelman |

Jim Goodnight |

|

William V. Hickey |

H. Fisk Johnson |

Maurice Lévy |

|

Mark G. Parker |

Paul Polman |

Steen Riisgaard |

|

Irene B. Rosenfeld |

Tarek Sultan Al Essa |

CONSUMPTION: WHY CHANGE?

|

Key insights |

Why Sustainable Consumption Matters

Without a fundamental shift in the way goods and resources are consumed, the world faces the prospect of multiple, interlocking global crises for the environment, prosperity and security. Sustainable consumption is a prerequisite for a more prosperous, safe and equitable global future. The costs of inaction are high.2

Pressures on current models of consumption are rising. The world's population is forecast to rise to 9 billion by 2050. Seventy million people are expected to join the global middle class every year between now and 2030.3 Demand for goods and services should follow. Without sustainable consumption, meeting those demands – and the collective expectations and aspirations which go with them – will become increasingly difficult, with more and more severe consequences.

The world's water systems will become progressively more stressed, while some countries may face "water bankruptcy" as a result of rising populations and changing weather patterns driven by climate change.4 Global food production will become increasingly inadequate, as an expansion of global population is coupled with a shift in diet of the emerging middle class towards more energy and water-intensive products.5 Globally, competition for scarce resources will increase. It will become difficult, if not impossible, for developed countries to insulate themselves fully from the social and other consequences this may have in poorer countries. Eventually, competition over access to resources, volatility over the price of resources, and widening global imbalances between the "haves" and the "have-nots" could lead to a popular rejection of economic and political globalization.6

Such a dire scenario of the future, extrapolating current trends 20 or 30 years from now, is not inevitable. Technological innovation may help avoid runaway climate change and mitigate the worst consequences of global warming already built in to the world's climate system. The capacity for societies to reinvent themselves in the face of adversity is extraordinary.

But avoiding such a scenario cannot be left to chance. Concerted action is needed to improve the likelihood that prosperity can indeed be achieved for a far greater number of people – with the life and business opportunities that that implies – without environmental degradation affecting the opportunities of future generations. Achieving wider global prosperity within a resource-constrained world is the greatest economic and political challenge of the 21st century.

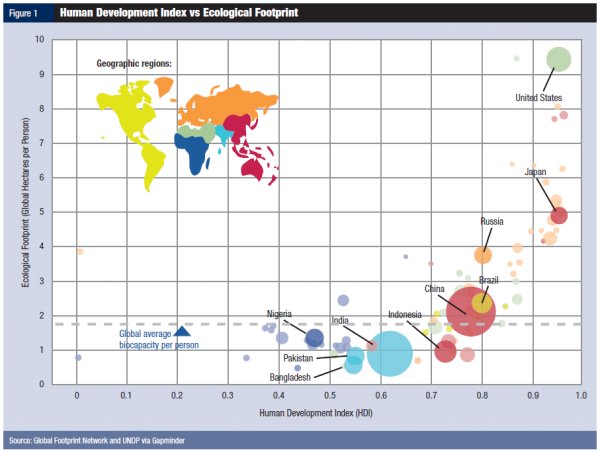

At present, virtually no country combines a high level of development as measured by the United Nations' Human Development Index with a sustainable ecological footprint (see Figure 1 below).7

A

A

Why Sustainable Consumption Matters To Business

In 2009, The Business Case for Sustainability provided a cogent argument for sustainability as an issue that should be incorporated into the strategy and operations of business, not just as a matter of stakeholder responsibility but as a matter of business survival and value creation:

- Managing Resource Risks: Sustainability matters to business because it reduces exposure to volatile and rising resource prices, to the risk of increased scarcity of resources and to the risk that these (carbon, water, waste) are radically re-priced in the near future. Embracing models of sustainable consumption across the value chain will provide stronger resilience against external shocks.

- Shaping The Regulatory Environment: Principles of sustainability are increasingly being incorporated into the regulatory environment. If businesses wish to flourish in this environment, they must make themselves active participants in its construction.

- Engaging Consumers As Citizens: The biggest drivers of corporate sustainability investments are consumer concerns, employee interest and government legislation.8 For business, driving sustainable consumption can be an effective long-term strategy for deepening authentic engagement with consumers and employees.

- Engaging Consumers As Customers: Consumers increasingly want to be treated as customers, demanding not only more sustainable products and services, but also greater transparency over sourcing and content of existing ones. At the same time, the speed, spread and changing patterns of use of the media are forcing businesses to adopt pre-emptive strategies to manage their reputational risk on sustainability issues. Engaging proactively with the sustainable consumption is one way of managing these challenges in depth.

- Driving Innovation: Businesses are the chief engines of value creation and innovation in society. The challenge of sustainable consumption presents an opportunity to enhance both, particularly when new partnerships and collaborations are opened along the value chain.

- Capturing Opportunity: In the end, sustainable consumption matters to business because there will be winners and losers in the new economy, and those that move most swiftly are likely to reap the greatest benefits. Embracing sustainable consumption now offers a pathway to future markets and profitability.

Why Sustainable Consumption Matters Now

The world economy is emerging from the deepest global recession in decades. To some extent, the depth of the recession has obscured the extent of the sustainability challenge – in some cases, where investments in improved resource development and management have been cancelled or deferred as a result of recession, it may have made things worse.

The global consumption trajectory remains largely unchanged. According to the World Wildlife Fund, resource consumption could increase to 200% of global carrying capacity by the 2030s.9 As argued below, incremental improvements in sustainability are not enough. A more fundamental, transformational shift in the way the world produces, consumes and manages value chains is needed.

The appetite for new business models has never been greater. In 2010, therefore, not only are the positive arguments for sustainability enhanced, but so is the opportunity for businesses to rethink the role of sustainability and to reconfigure their organizations to adapt.

CURRENT TRENDS TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY AND WHY A MORE FUNDAMENTAL SHIFT IS NEEDED

|

Key Insights Despite the recession, moves towards sustainability are accelerating, supported by a shifting consumer agenda, the rise of sustainable investment, increasingly supportive policy frameworks nationally and internationally, and attempts to redefine concepts of value and prosperity, incorporating environmental and other factors. These are positive trends – but even collectively, they are not enough to forestall environmental threats under most scenarios; yet, they also fail to catalyse opportunities for business and other stakeholders. |

Shifting Consumer Agenda

Consumers are becoming more active participants in the creation of the sustainable economy, demanding greater transparency over the origin and contents of the goods they consume, and increasingly aware of the broad sustainability challenge facing the world. This is a necessary but not sufficient first step towards a transformational change in consumption habits.

Part of the challenge is that there is not, as yet, any globally recognized definition of the sustainable consumer. Preferences and levels of consumption vary hugely between different societies, driven by level of income and culture:

- Consumers in the developed world are becoming increasingly sensitive to concepts of environmental harm and sustainability, but consumption levels there are already high. Achieving sustainability implies very substantial improvements in resource use and waste management as well as changes in product types and different models of consumption. A Deloitte study found that consumer behaviour is still principally dictated by price, quality and convenience, rather than by origin of products and sustainability content .10 Sustainable consumption remains niche. The disconnect between awareness and action is stark. For business models and consumption models to shift fundamentally, all consumption has to become sustainable.

- The developing world presents both the greatest opportunity for a growing consumer market and one of the greatest challenges in terms of achieving wider prosperity for current generations without undermining the sustainability of long-term prosperity. The prize is there for the sustainable economy to be built in emerging markets, without entering a phase of high-input/high-output consumption that characterizes the developed world. Concerns about the environment are often just as strong amongst people in the developing world as in the developed world, and in some areas stronger as they are often more directly affected, for example water pollution.11

Sustainability In Hard Times

In emphasizing the systemic vulnerabilities of the current global economic system, the recession has refocused the attention of consumers, businesses and policy-makers on the challenges of achieving greater systemic resilience and enhanced long-term prosperity. Since 2008, public and business attitudes towards their vulnerability to resource prices and potential scarcity have shifted. Sustainability is becoming part of corporate and consumer culture.

The need for this shift can be seen in upward trends in resource prices. While the global recession temporarily eased the immediate pressure on the prices of energy, food and natural resources that was manifested in 2008, commodity prices have resumed their inevitable upward path since the beginning of 2009. Long-dated oil prices have increased to nearly US$ 100 a barrel, some US$ 20 higher than two years previously. Despite the deepest recession in more than a century, global consumption fell by only 0.3%.12

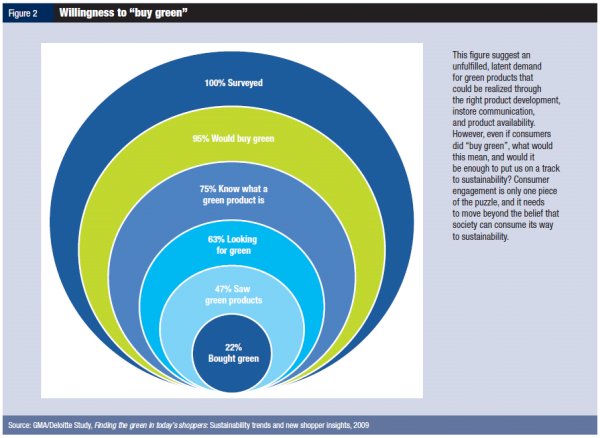

Fears that the economic downturn would distract attention from the importance of sustainable consumption have not been realized as public attitudes and demand for sustainable products have remained remarkably constant through the recession. For example, some 95% of American consumers say they are willing to "buy green"13 (see Figure 2 above) and 44% say their "green" buying habits have not changed, and more than one-third report that they are more likely to buy sustainable products.14 The market for products is, in fact, predicted to grow significantly: a recent report for the German government suggests that Germany will earn more money from green products than from car production by 2020.15

Though business action and investments have necessarily been constrained by financial conditions, sustainability has also remained high on the agenda of business. The MIT Sloan report found that less than one quarter of survey respondents said that their company had decreased its commitment to sustainability during the recession.16 Many of the actions undertaken by businesses have positive, clear bottom line implications in the near to mid term – reducing energy use and its cost, reducing water use and its cost and reducing the use of carbon. But while these actions have clear benefits to individual businesses, the real prize – sustainability along and across value chains – is far from being achieved.

Governments, meanwhile, are increasingly directing public investments towards projects that measure or enhance sustainability. For example, the US government has required federal agencies to make improvements in their environmental and energy performance. Across the world, fiscal stimulus packages launched in response to the financial crisis have given a significant role to "green growth" – not just in the US and Europe, but also in Brazil, India and China.17 This may herald the beginning of a broader shift to sustainability criteria being increasingly important in the award of government contracts.

Rise Of Sustainable Investing

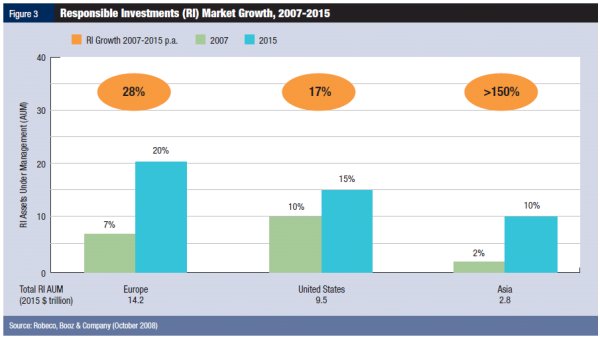

In line with changes in consumer, business and government attitudes, investment patterns are increasingly supportive of the shift towards sustainable business models.18 The penetration of responsible investments19 is expected to rise rapidly over the next few years – from under one-tenth of assets under management to approximately one-fifth, or US$ 26.5 trillion (see Figure 3 below). This represents an extraordinary depth of funding availability for sustainable businesses, at a time when funding for other businesses has become far more difficult to obtain.

In September 2009, the non-profit Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) was launched at the meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative in New York, with the aim of sharing information on what works and what does not, defining and agreeing common language and measures of performance – the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS) – and helping influence governments to produce regulation which acts as an enabler of impact investing.

This is part of a series of collaborative initiatives involving the financial industry, including:

- The UN Principles for Responsible Investment, which have attracted more than 640 signatories so far, with combined assets under management of over US$ 14 trillion

- Ceres, which directs the Investor Network on Climate Risk (INCR), a group of more than 80 leading institutional investors with collective assets of more than US$ 8 trillion

- The P8 Group, which brings together senior leaders from some of the world's largest public pension funds to develop actions relating to global issues and particularly climate change The investment community, and the financial means which it represents, is driving sustainability forward. Just as government is beginning to create the appropriate regulatory framework for businesses to invest, sustainable investment could be the financial enabler which allows aspiration to become reality, and which rewards companies for investments made in sustainable infrastructure, products and innovation.

The Evolving Public Policy Framework On Sustainable Consumption

A key enabler for a fundamental shift towards sustainable consumption is a workable public policy framework at the national, regional and global level. Here, progress is mixed. Slowly, the sustainability agenda has moved from the outer limits of global public policy discussion – with the controversial 1970s The Limits to Growth report – towards its core. The 1980s Brundtland Commission was followed up in 1992 by the Rio summit.20 In 2002, the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (JPOI) called for a 10-year framework of programmes to accelerate "delinking economic growth and environmental degradation", leading to the current Marrakech Process on Sustainable Consumption and Production, under the auspices of the United Nations.21 The gradual institutionalization of sustainability issues in global policy frameworks is welcome, but progress here has been patchy, and awareness among business is insufficient.

Though sustainability is increasingly being linked to existing public policy frameworks on climate change and biodiversity, there is not yet specific global regulation of sustainability. Nor is there global policy consensus on the framework and approach needed. The Marrakech Process is designed to provide a framework for global, regional and national sustainable consumption and production programmes. So far, while all regions have identified priories and programmes, there is great variance in their progress. Only 35 countries worldwide have developed or are in the process of developing their national sustainable consumption and production programmes. In some countries, these programmes represent major progress; but collectively, they are not enough.

- In Europe, the European Union has taken important steps to promote sustainable consumption, most significantly the July 2008 Action Plan on Sustainable Consumption and Production, expected to significantly boost demand for sustainable products. The EU Ecolabel scheme, set up in 1992, is currently being revised. Green Public Procurement, allowing public bodies to take account of sustainability considerations when purchasing products and services, is a major part of that action plan.

- In Africa, the permanent African Ministerial Conference on the Environment approved a 10-year framework for sustainable consumption and production in 2005, identifying priorities in energy, water and sanitation, habitat and sustainable urban development, and industrial development. Several African countries are pursuing their own programmes, and a pilot project on eco-labelling in Africa is underway.

- In the Asia-Pacific region, several countries have engaged in reform of the tax system, green procurement, enhanced disclosure requirements or product stewardship tools to level the playing field for sustainable products and services. China and India have become actively involved in the Marrakech Process, pointing to the increasing interest of the world's largest growth markets in configuring their economies for sustainable growth.

- In the Americas, while neither the United States nor Canada has adopted specific policy frameworks for sustainable consumption and production, legislation and regulation on environmental issues is increasingly shifting growth models towards sustainability. In Latin America, regional environment ministers have launched a regional sustainable consumption and production strategy.

In spite of pressures from local concerns in more and more geographies and the increasing involvement in global governance processes, the sustainability agenda has not yet become a sufficiently mainstream part of public policy. That process needs to deepen and accelerate.

Redefining Prosperity, Redefining Value

Governments, consumers and businesses are redefining what constitutes prosperity and value. Focus has increasingly shifted from measurable throughputs of resources and purchases of goods to less easily defined concepts such as well-being, welfare and quality of life. Amartya Sen, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics-winning economist, has redefined "development" in terms of enhancing life opportunities, choices and freedom, taking higher incomes in developing countries as a necessary but insufficient condition for that to be achieved.22

The intellectual argument for broadening measures of prosperity – and for more accurately valuing environmental and other externalities in national and business accounting – has been ongoing for decades. What has changed in recent years is the seriousness with which redefining prosperity has been adopted by governments. The idea of introducing measures of sustainability into measures of national income was boosted in September 2009 with the publication of a report commissioned by French President Nicolas Sarkozy, The Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.23 As national accounting standards move towards measures that incorporate sustainability, it is highly likely that the incentive structures that states create – for businesses and for individuals – will shift accordingly.

Is It Enough?

Unfortunately, these current trends towards sustainability are welcome but insufficient. The shifts above are focused on incremental, rather than transformative, change. While they may improve sustainability at the margins, they are rooted in a model of consumption that is itself unsustainable. Working within the existing paradigm means that, despite best efforts, incentives for business investment are not sufficient. Collaboration across value chains is deficient. Public policy frameworks are neither ambitious enough nor adequately coordinated at the global level. The shifting consumer agenda is too limited.

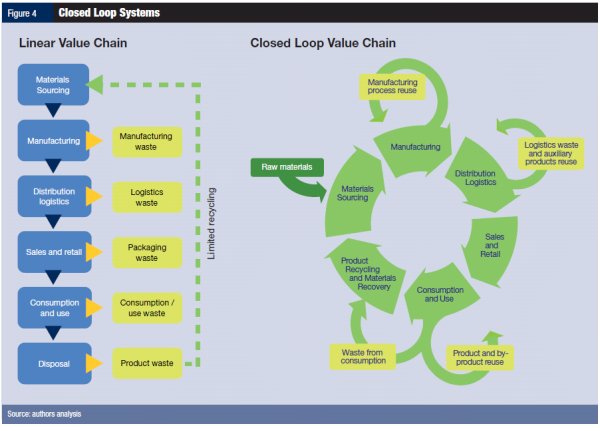

Ambitions must be raised, and visions broadened to the system as a whole. Changes in lifestyles and consumption habits will be needed from consumers, not just an expansion of the number of "green" consumers; businesses will need to define new business models, focused on value creation rather than material throughput; work towards closed loop systems (see Figure 4 above); and governments will need to institute enabling policies and regulations that price resources at their true cost and measure sustainable prosperity at its true worth for future generations.

In many businesses, the first steps on the path towards a sustainable future have already been taken, and in some cases substantial investment programmes are already in place. Most of those have involved reducing the resource intensity of production, with clear and rapid gains – in terms of environmental benefits, reduced costs, increased profitability and a leadership position within the business community. But the sustainable future is not just about greater resource efficiency within businesses, or even about greater resource efficiencies within and across value chains. It is not just about making standard business practices "less bad" – it is about mainstreaming those practices which are "actively good". The old paradigm for the global economy – focused on throughput of resources, consumption of products, limited measures of prosperity and underpricing of externalities – is being discarded. A new normal must be defined, and a path set out to achieve it.

WHERE DO WE WANT TO GO? DEFINING THE "NEW NORMAL"

|

Key Insights The challenges of sustainable consumption require rethinking the fundamental tenets of the economy. The world economy must move towards a "new normal", bringing about systemic change in consumption, production and the way in which value is created. |

The new normal for the global economy is one in which consumption is decoupled from negative environmental and social impacts, driven by a combination of innovation, evolving consumer values and more accurate product costs. In the end, it is not a world defined so much by scarcity and sacrifice, as a world defined by innovation and a new abundance.

The "new normal" is an economy in which:

- Consumers Are The Driving Force: Through more meaningful engagement and co-creation, consumers are positively engaged with the benefits of sustainable consumption to themselves, their families and their communities. They are empowered through meaningful information about products in the marketplace, which has been improved with better metrics and more standardized communication platforms. Consumers view a product as a means to a solution or enhanced experience rather than a product as an end in itself.

- Consumption Is About Loops, Not Lines: Through better design and life-cycle thinking, consumption and production ecosystems become closed loops, producing no outputs as waste through their life cycle. As such, the concept of waste disappears, as all by-products retain an intrinsic value to feed into other systems. Even food spoilage and waste are minimized and turned into biofuels, compost or animal feed.

- Collaboration Is A Key: Companies view the areas in which they collaborate as important as the areas in which they compete. This collaboration happens both along and across the value chain through management, reduction and elimination of impacts that transcend the boundaries of direct control of any single company. Product waste and duplication is improved through interoperability of products.

- Core Business Practices Are Sustainable: Company competitiveness and profitability are inextricably linked with their achievement of sustainability objectives. The depth of this relationship goes to the core values ascribed to products and services, materialized through life cycle design and innovation. Relationships with suppliers and buyers are based on greater trust through which long-term contracts and relationships are emphasized, providing greater traceability of both products and their impacts.

- Public Policy Frameworks Support Sustainable Consumption: Governments pursue policies to enhance wellbeing of citizens and the environment, as much as traditional economic growth. Natural resources such as water or carbon are priced according to their value within the structure of the economy and environment as a whole, while externalities which are currently unpriced or underpriced, such as landfill waste or toxins, are appropriately accounted for through market mechanisms.

This "new normal" is in many ways so different from today that it is difficult to visualize. The following two pages provide another perspective on the concepts above from the viewpoint of a CEO looking back from 2030.

Looking Back From 2030

Speech made by Adreanna Lopez, Chief Executive Officer of ConsumerGoodsInc from 2012-2021, to celebrate her acceptance of the Nobel Prize for Economics in October 2030.

"Thank you. I want to start by acknowledging two groups of individuals without which ConsumerGoodsInc's combination of commercial success, consumer engagement and sustainable innovation would have been impossible to achieve. First, our employees, now more than a million strong, whose involvement in every stage of redefining our strategy has been crucial. Second, our customers, who have been so important in helping us shift to our model of "shared value". Unlocking our customers' ideas as innovators and mobilizing their engagement as citizens has been vital to our success.

ConsumerGoodsInc has, indeed, achieved astounding success since its foundation in 2010, when I joined a small executive team to explore how the type of model developed by eBay could be applied to our sector. It was not the easiest of times to launch a new corporate entity. At that time, the consumer goods industry was just coming out of the worst financial crisis in 75 years, and emerging into what some called the "long crisis of globalization". At the time, our industry's business model saw the ever-increasing consumption of goods as the end goal. That model was needlessly wasteful of natural resources, mispricing scarce resources and failing to capture the huge efficiency gains available both along and across the entire value chain. It was a model that, in the end, could provide neither the long-term growth that we needed as businesses, nor the long-term prosperity we needed as global citizens. It was, in short, unsustainable.

But the confluence of environmental and economic crisis which the industry experienced in 2010 spurred us to rethink our businesses and, in the process, to develop and capture new markets. And, in committing to long-term economic, environmental and social sustainability across all our business lines, we were part of the shift from a world of resource consumption to a world of value optimization.

ConsumerGoodsInc was instrumental in leading the way for two major changes in how our industry and, by association, the global economy operates today. First, with our Waste Partners programme, we revolutionized the way we worked with players through our entire value chain to eliminate the concept of waste. As a result, today's consumers take a world without waste for granted: operating a low-carbon, closed loop value chain with efficient resource use and collective stewardship across life cycles is part of businesses' licence to operate.

Our efforts to find ways to reduce our material footprint were small to start, but became larger and larger as other companies started to imitate us, and we realized that, by facing what were essentially systemic challenges, we were also creating massive opportunities. As an industry, we began to innovate ways to deliver the "smart" prosperity we are familiar with today. In 2012, we transformed the Waste Partners programme from a closed, supply chain system to an open-source platform that our consumers could join – not only could they feel more secure about their purchasing decisions by knowing exactly what waste we were producing in which countries, they could advise us on material choice and help us make connections to other businesses that turned our excess material into a valuable input elsewhere. As more and more stakeholders, including our competitors, joined the programme, the bottomup wave essentially forced policy-makers to provide the right incentives to allow true valuation of all materials and externalities.

If sustainability started off as the creed of efficient resource management, it has ended up helping us build a new economy which values resources and products differently. This is at the heart of ConsumerGoodsInc's second key contribution to today's economy – our True Value for Money movement, which started almost accidentally as a campaign launched in 2016. Through this movement, we worked with our customer base to rethink the value proposition of the goods and services we provide. As a result, today we produce nothing more than is required to enhance and improve consumer lifestyles and well-being. While we have not yet managed to convert all our product ranges into dematerialized services and experiences, we have certainly managed to get across the message that we are no longer selling "stuff"; we are enhancing people's well-being overall.

Sustainability to us has therefore been a catalyst for innovation, not just in terms of the facilities and technologies – the smart grids and local generation technologies which now allow 80% of houses to run on local power sources, and the breakthroughs in waste reprocessing and capture that have taken us so close to zero waste – but also innovation in defining what value means to the economy and how it can be delivered. In doing so, ConsumerGoodsInc has helped unlock significant financial rewards.

And while those rewards have spurred fierce competition within the industry, new forms of collaboration have been a key in ensuring that we race to the top. Open source architectures make it easy to share non-competitive information across entire value chains, and we have developed targeted industrial ecosystems that combine competitive advantage with benefits to our wider community and society. We have also put the consumer at the core of the collaborative process to help us design more high-impact, high-value consumer experiences that can profitably fulfil needs and aspirations without costs to the global commons.

But the roots of our success, as I see it, are wider still. ConsumerGoodsInc, like many of our competitors, has invested boldly in thousands of small, experimental initiatives, models and promising technologies that we felt could transform our businesses. We constructed new languages and metrics to communicate more clearly with our boards and external investors, and we have found patient capital to suit our long-term commitments. We have been open about what has worked and what has not, since we knew the journey was about learning as well as succeeding. We have accepted that every CEO should be judged on his or her contribution to the firm's entire stakeholder group, with the environment as a critical component. And we have been surprised along the way by some of the advantages of embracing an agenda for sustainable consumption – we benefit from greater levels of employee and customer loyalty than any other large consumer goods company.

Together, we have helped build "a new normal" for the world economy. And while smarter regulations from governments and incentives for sustainable investing have been essential to us achieving our goals, we are proud that it has been business, in partnership with consumers, investors and other stakeholders, which has both led the change and embodied the change to a more sustainable and successful path for the economy as a whole. Finally, I want to point out that, despite the fears that many had in 2010, all this has been achieved without sacrificing established lifestyles, while bringing nearly all of the world's 8 billion consumers online in all global markets, the very markets where many of ConsumerGoodsInc's most innovative ideas were produced.

It is an amazing honour to accept this prize, and almost ironic that, while shifting global perceptions of waste and value, we were merely doing our best to innovate our way to success in a fragmented and competitive market in a tumultuous landscape. It is even better to celebrate this success knowing that the model we pioneered has been accepted, adopted and often improved, reaching the lives of almost every citizen on the planet right now, without compromising the lives of future generations to come. Thank you."

HOW WE CAN GET THERE

|

Key Insights Businesses need to "own" the sustainability agenda within their organizations, starting with the board and then engaging with employees and other stakeholders. The obstacles to building sustainable consumption are definable, and the means to overcome them are achievable. The opportunities this will create are now visible – they are within grasp. |

Making The Journey

In 2010, the challenges of balanced business ecosystems seem far off. Getting there involves a difficult journey, but it is not an impossible one. Four practical, achievable steps will help vanguard companies start this process, highlighting the obstacles that must be overcome and the opportunities that can be seized by businesses, leaders and citizens in the process.

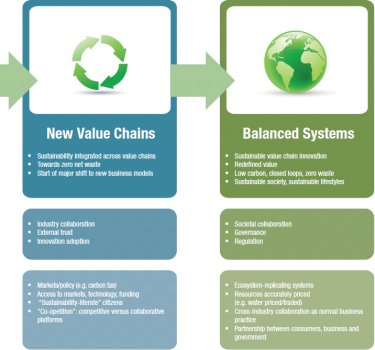

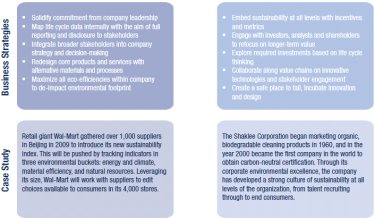

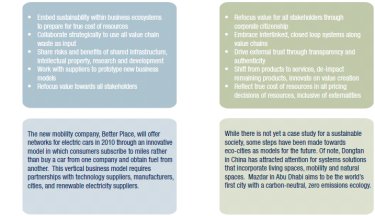

The first step is to firm up the foundation, as the current leading business practices of today become standard business practice and sustainability strategy is integrated into business. This is "relative sustainability", where steps being made are important but still incremental from where we are today. The second step is rebuilding business, in which sustainability is integrated throughout the business, new business models are piloted and demonstrated as being viable. The third step, new value chains, is the beginning of a major shift to new business models, in which sustainability is integrated across value chains and entire chains are moving towards zero net waste. The final step leads to balanced systems, in which innovation drives sustainable value chains and value is redefined for all stakeholders. This results in a low-carbon system with closed loops and zero waste both along and across value chains, in which sustainable society and sustainable lifestyles are realized.

A picture of this four-step journey emerged from discussions during the Driving Sustainable Consumption roundtable workshops and different Forum events. The above visualization is explained in more detail in the following pages, with more information on the barriers, enablers and specific strategies to help companies change the way they do business. Also included are four mini case studies to help bring each of the steps to life.

When taken in the context of the rest of the roadmap, these four steps can simplify the journey and help catalyse action through individual companies and along entire value chains.

Roadmap For Sustainable Consumption

|

|

|

|

|

|

What It Takes

Getting to the summit of sustainable consumption is not a single process, it is many. Nor is getting to the summit outlined above the work of a single company. It will be achieved through the effort, collaboration and innovation of many companies, working with their suppliers, collaborating across value chains and engaging with their customers. Governments must be involved to set the appropriate frameworks and incentives. Society as a whole must be engaged. Some will move quickly, others more slowly. Once the summit is defined, and the intention to reach it is acknowledged, the journey will become easier.

The journey consists of changes on four levels:

- First, a change in business leader mindsets, to support the goal, and to begin to change consumer behaviours and corporate attitudes towards the provision of value

- Second, organizational change, to embed sustainability into the core of businesses and institutions, so that it becomes a part of the business ways of thinking and working

- Third, industry-wide change, by promoting collaboration across suppliers, customers, investors and talent pools to build sustainability into extended value chains

- Fourth, systemic change, involving major public policy changes to shape not just businesses, industries and societies but the global economy and trading system

While businesses can and do have a major influence on systemic change – demanding a clear and consistent policy framework from governments to allow for long-term investment decisions – the three first levels of change are the starting point for corporate leaders, and they are the starting point here.

What Can Individual Businesses Do To Build Sustainability?

To overcome these obstacles and to unlock these opportunities, organizations need to fundamentally change the way they think and act.

- Make The Journey Towards Sustainability As Tangible As Possible. Leaders need to sign up to clearly defined targets and performance metrics for measuring their success in achieving sustainability. They need to take collective accountability for these goals. Initial focus should be on gathering momentum and creating positive energy around sustainability by mobilizing action groups to achieve quick wins and celebrating success.

- Engage All Levels Of The Company. Embracing sustainability needs to start at the level of the board, introducing it as a core component of strategy, seen as a critical determinant of future growth and profitability. This requires a compelling and shared vision of what sustainability means for their business, and how it can drive shareholder value and deliver tangible financial benefits. But once the leadership team of the company is fully committed, sustainability must be embedded throughout the business, through education and alignment of visions of the company's role and future.

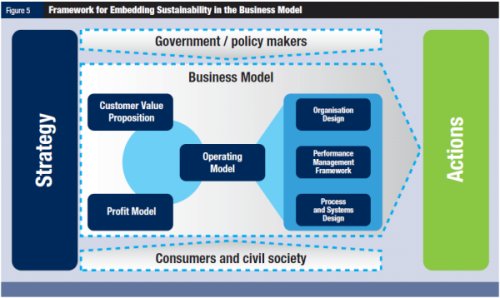

- Change The Business Model. Mainstreaming sustainability into the company will have implications for the customer value proposition and profit model. This requires a cross-functional programme with the right people, a robust governance structure and a clear mandate to drive sustainability throughout the organization. Performance should then be evaluated against a set of agreed critical success factors.

- Shift Values And Culture. Corporate culture and values may need to evolve in order to reflect the objectives of achieving genuine sustainability. Rewards packages and other performance drivers will in most cases need to be updated to incentivize sustainable behaviours. As sustainability will be vital for future growth, activity should focus on driving sustainability innovation by establishing design incubators to test initiatives in a safe environment.

- Engage All Internal Stakeholders. Managing and implementing change will require internal stakeholder engagement and communications initiatives to build sustainability into the company's DNA and create support and demand for sustainable ways of working. For progress towards absolute sustainability to be self-sustaining rather than managed, all internal stakeholders need to be involved. A sense of ownership of sustainability issues within an organization is directly linked to the understanding of sustainability issues.24

- Implement Sustainable Practices Across And Along Value Chains. Once sustainability is embedded in the company itself, the next challenge will be to establish optimal levels of sustainability and remove waste across their value chain, involving suppliers, customers, talent pools and investors in the task. The key will be building collaborative partnerships based on trust and mutually beneficial aims, and establishing standard metrics for measuring sustainability and success. Companies will need to "role model" sustainable behaviours and be seen to lead the way by implementing sustainability initiatives and measures across their value chain. This should include implementing parameters and measures for suppliers, proactively engaging with customers and investors to build their awareness and encourage more sustainable consumption, and attracting and recruiting people from the talent pool who are dedicated to achieving absolute sustainability.

The framework shown below25 helps businesses align their operating model with changes in their Customer Value Proposition and Profit Model. The framework shows the key components of the operating model, which can be updated to identify specific actions.

Footnotes

1. See Sustainability for Tomorrow's Consumer: The Business Case for Sustainability, World Economic Forum, 2009, available at www.weforum.org

.2 On the costs of climate change, and the economic rationale for mitigation, see Nicholas Stern, The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review, 2007

3. Middle class here refers to those with an annual income between US$ 6,000 and US$ 30,000. World Business Council on Sustainable Development, Sustainable Consumption Facts and Trends, 2008

4. See Managing Our Future Water Needs for Agriculture, Industry, Human Health and the Environment, World Economic Forum Water Initiative, 2009

5. See The Feeding of the Nine Billion: Global Food Security for the 21st Century, Alex Evans, Royal Institute for International Affairs, 2009

6. Several of these issues have been highlighted in the work of the World Economic Forum's Global Risk Network. See, in particular, Global Growth@Risk, 2007

7. A sustainable ecological footprint is measured in terms of the world's total biocapacity divided by population. For more explanation of methodology and the figures, see www.footprintnetwork.org

8. See The Business of Sustainability, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009

9.WWF, Living Planet Report, 2008

10. Study conducted by Deloitte LLP for The Coca Cola Retailing Research Council, Europe

11. Unilever research conducted by The Futures Company, 2009

12. Relates to the concept of World Ecological Day (the day in the year when the world consumes more resources and generates more waste than global ecosystems can produce or absorb) shifting back only one day, to 25 September 2009. For an explanation of the concept and its applicability, see the New Economics Foundation, www.neweconomics.org

13. See Finding the Green in Today's Shoppers: Sustainability Trends and New Shopper Insights, conducted by Deloitte for the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), 2009

14 See 2009 Cone Consumer Environmental Survey . 15. Report by Roland Berger, cited in the Financial Times, 23 November 2009

16. See The Business of Sustainability, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009

1.7 See, for example, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, 2009. For a top-level view on the green new deal, see The best and worst policies for a green new deal, Briefing by E3G and WWF, November 2009

18. See Responsible Investing: A Paradigm Shift, From Niche to Mainstream, Robeco/Booz & Co., 2008

19. Sustainable investing means including environmental and social factors in investment decisions whereas responsible investing (RI) is overarching and also includes socially responsible investing which takes ethics as the starting point rather than profit maximisation.

20. The Limits to Growth report has been widely criticized as having failed to take into account technological innovation as a major factor in boosting long-term growth. But the fundamental thesis of the report – of a disconnect between growth and resource availability – was correct. The Brundtland Commission, officially the World Commission on Environment and Development, led to the publication of Our Common Future, published in 1987

21. More information on the Marrakech Process can be found at http://esa.un.org/marrakechprocess/

22. See Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press, 1999

23. An English version of The Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress report is available at www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm

24. See The Business of Sustainability, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009

25. Deloitte Framework for Embedding Sustainability in the Business Model

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.