Report was prepared in collaboration between Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and the World Economic Forum, January 2009

PREFACE

The World Economic Forum's Consumer Industries community is pleased to present this report as part of the Sustainability for Tomorrow's Consumer initiative. The Consumer Industries community comprises leading companies from the agriculture, food and beverage, retail and consumer goods industries. This initiative was kicked off in response to the mandate of consumer industry chief executives at Davos in January 2008. These chief executives had the vision to view sustainability as an opportunity for innovation and growth, and with support from the consumer industries community, this initiative has spent the past year exploring these opportunities in more depth.

The three pillars of this initiative are:

- The Business Case for Sustainability: Understanding the implications of increased consumption and resource volatility on cost structures and business models and establishing the need for disruptive innovation

- Design Innovations for Consumer Industries: Exploring breakthrough lifecycle innovations towards a sustainable consumer basket

- Shaping the Framework Conditions: Having an impact on the future playing field for sustainability by engaging stakeholders such as investors and regulators

This report aims to present the business case for sustainability for consumer industries. The analysis conducted as a part of this project suggests that supporting sustainability is not only responsible, but also makes good business sense. In addition to presenting the change imperative for businesses, the report shares learning explored through this initiative to guide companies along the path to sustainable consumption and growth.

A broad network of partners has contributed to the ongoing success of this project. We express appreciation for the Project Board and Advisory Board for their input to the initiative and specifically their attendance at the workshops held throughout the year. Along with numerous meetings and calls, three workshops were conducted, in Beaverton, Oregon, in May (hosted by Nike); New York City in September as part of the Forum's Industry Strategy meetings; and New Delhi in November in conjunction with the Forum's India Economic Summit. This report represents the collective input of more than 100 individuals who attended these and other meetings to discuss this issue. Partner companies also provided input to the in-depth life cycle analyses conducted for a basket of consumer products as part of background research and analysis.

The initiative's Project Board includes: Best Buy Co., Estée Lauder Companies, Nestlé, Nike Inc. as chair, PepsiCo, S. C. Johnson & Son, Sealed Air Corp., The Coca-Cola Company and Unilever. Special thanks to Kraft Foods, Nestlé, Nike Inc. and Unilever for providing specific data to support business case analyses.

The Advisory Board includes Aron Cramer of Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) as chair, Susan Burns of the Global Footprint Network, Brian Collins of Collins Design, David Cook of The Natural Step, Helio Mattar of The Akatu Institute for Conscious Consumption, Malini Mehra of Center for Social Markets (CSM World), Ted Howes of IDEO, Mindy Lubber of Ceres, Simon Zadek of AccountAbility, Jimmy Wales of Wikipedia.org and Bill McDonough of McDonough & Partners.

This report was produced in partnership with Deloitte – our project adviser for this initiative – and special thanks are due for their support of both content and the year-long process that has produced this new insight on business and sustainability.

|

Robert Greenhill |

Sarita Nayyar |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Issue

There will be a tripling of the global middle class1 by 2030. Each year, at least 70 million people will be entering this income bracket in purchasing power parity terms. If this projection plays out, almost two billion people will have joined the global middle class by 2030, bringing almost 80% of the world's population into a middle income bracket.2

On the other hand, three planets Earth would be required were everyone to adopt the historic consumption patterns and lifestyles of the average citizen in the United Kingdom; and five planets if they were to live like the average North American.3.

This conundrum creates a systemic challenge to our world economic system and the business community: how is it possible to create wealth for tomorrow's consumer and value for tomorrow's businesses in an environmentally sustainable manner?

The Dialogue

This question inspired chief executives of the Consumer Industry community at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2008, to launch a 12-month discussion: What does sustainability for tomorrow's consumer mean? What is the business case to start meeting tomorrow's consumer demands today?

The community developed four hypotheses for consumer industry executives and experts to challenge:

- Global consumption patterns are out of balance, with demand for resources and commodities growing more rapidly than supply despite the current recession

- Resource use intensity of the consumer industries and associated supply chains is commensurate with underpricing of natural resources, and not reflective of true resource costs

- The financial sensitivity of consumer industry companies to resource volatility and constraints is severe

- New business opportunities will emerge through a fundamental rethinking of what successful business models may look like in the future

Over the course of 2008, a series of workshops was held in the US and India to explore these themes. Over 100 consumer industry executives and experts in sustainability, business strategy and product design took part in the discussions. Additionally, quantitative analysis of resource intensity and business impact of resource scarcity on business profitability was conducted to evaluate the scale of the challenge faced by companies.

During the 12 months of discussion, the financial crisis took hold and the threat of economic slowdown became a reality. Executives remain convinced of the underlying growth potential of consumption from the new middle class, but felt that the financial crisis held critical lessons for the sustainability agenda: 1) there is a need to address systemic risks (financial, social, environmental) before they fracture the imperfect institutions and governance that currently restrain them; 2) the crisis creates an opportunity to build back new and different business management approaches; 3) in today's global system, wider collaboration, although difficult, is the only effective way to address a systemic crisis.

Findings

Four business imperatives for a more sustainable tomorrow emerged from the dialogue:

- Meaningfully engage consumers – Consumers are confused about sustainability, and new ways to reshape the role of consumers will be required to proactively engage them in an experiential relationship, beyond the purchase of a product. As consumers remain price sensitive, the onus will be on business innovation to meet tomorrow's demands.

- Innovation is the only way forward – There is a long-term need to dematerialize the economy and shift to new value-driven relationships which focus on meeting consumer needs, and selling value rather than just selling more "stuff". Incremental improvements will not be adequate to meet the challenge of sustainability.

- Rethink core business models – With more value placed on externalities, a change from a build, buy, bury mentality is inevitable. There will be no "going back to normal" as the relationship between product, service and consumer irreversibly evolves.

- Collaborate along the value chain and close the loop – New forms of collaboration such as open sourcing will be required with supply chain partners and consumers, based around resource efficiency, product take-back, and reverse logistics. Information sharing will become more common, for example, through standardization of packaging materials to boost recyclability.

In addition, shaping the policy to support and align incentives acts as a fifth imperative and a catalyst for these four.

Next Steps

The implications of these findings are clear: there are systemic risks to sustainability which are embedded in the current economic structure, which will need to be addressed in a breakthrough manner rather than through incremental improvements. It is up to the consumer facing industries to be proactive, and they will need to engage with their entire markets and supply networks. New forms of collaboration will be required to create a competitive commercial environment that enables room for innovation and value creation for all.

During the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2009, the Project Board which has led this work is discussing its implications with a wider group of chief executives in the Consumer Industries. The aim is to gain feedback and support to design and launch a major new initiative for the Forum, centred on the business innovations that will be required to meet the demands of tomorrow's consumer and tomorrow's stakeholders in a sustainable manner.

|

A working proposition for the new sustainability initiative: Tomorrow's Consumer

|

A further session at the Annual Meeting 2009 is inviting executives from other industries to discuss this issue, exploring whether these imperatives resonate with leaders from consumer facing industries such as automotives, aviation, ITC, media; and from industries within the supply chain such as chemicals, mining and metals, logistics and transport. Is there appetite from other companies in the value chain to help build such an initiative?

Companies that take the lead on sustainability will be market makers rather than market takers. By showing the consumer that there is no need to sacrifice price and quality for sustainability, tomorrow's successful businesses will meaningfully engage the next two billion consumers, the largest new market the world has ever known. In doing so, they will secure stronger markets and a better business tomorrow. Politicians and governments are looking for ways to regulate a better world and price externalities without compromising development or living standards. If business can build sustainability without compromise to the consumer and voter, they will pave the way for better and more welcome regulation.

Getting involved

As this initiative expands through 2009, interested partners should please contact:

Sarita Nayyar, Senior Director, Consumer Industries, Sarita.Nayyar@weforum.org

Randall Krantz, Associate Director, Environment Initiatives, Randall.Krantz@weforum.org

Marcello Mastioni, Associate Director, Retail & Consumer Industries, Marcello.Mastioni@weforum.org

|

"This is not the same old sustainability challenge. This is not a fringe discussion any more about using soft power. We're beyond that. Sustainability is no longer a 'nice to have'. It has become a human security and survival issue. We need a progressive risk management agenda to help improve the lives of everyone who participates in tomorrow's global economy." Environmental and sustainability cluster summary report (incorporating the viewpoints of 120 international sustainability experts from public, private and academic sector), Inaugural Meeting on the Global Agenda, Dubai, November 2008 |

BUSINESS CASE RATIONALE

Sustainability As An Issue Of Relevance

Sustainability has received an unprecedented amount of attention over the last several years. Chief executives have aggressively set priorities and goals; companies have issued sustainability reports and undertaken numerous initiatives focused on enhancing environmental performance; and new reports and articles are released on the topic every week. Given this focus and attention, why the need for yet another initiative and report highlighting the risks and opportunities associated with sustainability?

Consumer industry chief executives, in partnership with the World Economic Forum, undertook this initiative, "Sustainability for Tomorrow's Consumer", because they recognize the need to view sustainability as an opportunity for innovation and growth rather than a new campaign or a response for the purpose of regulatory compliance. This initiative represents the recognition by industry leaders that there is a need to go beyond the historical response to sustainability – largely focused on incremental improvements – to achieve a desired future state where human consumption is in balance with natural systems.

Sustainability in the context of this initiative is focused primarily on environmental impact, but not at the expense of the social or economic fundamentals. As such, it is important to take a broader view than just environmental sustainability. The 1987 UN Brundtland Commission developed one of the first definitions of sustainability: "Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."4

Several factors are contributing to heightened interest in sustainability by business: increasing volatility in commodity and energy prices, more public and investor scrutiny of the traditional supply chain, the flattening world of information and complexity of value webs, and the inevitable long-term need for the economy as a whole to innovate to improve resource use efficiency in order to both deliver wealth for tomorrow's consumer and sustain value creating companies. These factors mean that some forward-thinking business leaders are becoming more interested in sustainability as an issue right across the economic system, and how they can collaborate to make this shift, rather than just how they each might be able to reduce cost or meet regulatory requirement within their own company.

The Immediate Economic Environment

"This is not the same old sustainability challenge; this is not a fringe discussion about soft power: we're beyond that. This now requires hard power. It is a security and survival issue." This was the conclusion of more than 120 environmental and sustainability experts who met across 12 Global Agenda Councils at the World Economic Forum's global brainstorming event held in Dubai in November 20085. The current refrain, "a crisis is a terrible thing to waste", seems particularly apt.

Given the current state of the global economy, many consumer industry company leaders will have no choice but to focus in the short term on cost cutting and even business survival. However, the sustainability challenge is a shakeout in the making. The current economic environment offers a wonderful opportunity for companies to reflect on how they are run today, and what needs to be different to be prepared for the future. As the framework conditions that govern business are not within the direct scope of just one company, a collaborative setting provides not only the leverage of scale, but also the opportunity to redefine how performance is measured.

Economies moving out of the downturn and into a recovery cycle will present very compelling situations for sustainable technologies and products, though some challenges may remain, particularly in developing economies. As companies plan ahead, there is the question, "When will things return to normal?" It is increasingly likely that there will never be a return to the "normal" of the past two decades. Prices will stabilize over time and parts of the economy will be picking up again bit by bit, but it may take years before economies return to previous levels and when they do, the landscape will look very different than it does today.

Guiding Hypotheses

The realization by industry leaders that there is an increasingly strong business case for sustainability set the tone and agenda for this work. This premise resulted in the development of a guiding set of hypotheses which are addressed in this paper:

- Consumption imbalances: Despite the current economic downturn, global consumption patterns are out of balance – with demand growing more rapidly than supply – and this imbalance is likely to grow exponentially in the future

- Resource efficiency: The resource intensity of consumer industry products and business models is significant, not well understood, and not reflective of "true" resource costs

- Bottom line: The financial sensitivity of consumer industry companies to resource constraints is severe and will likely be exacerbated in the future when resources begin to be priced more accurately

- New opportunities: There is a remarkable opportunity associated with fundamentally re-valuating and innovating how we do business and who we do business with as significant new markets open up globally

New business models are needed to respond to these challenges. Companies that embrace these emerging realities will be best positioned to succeed over the medium and long term.

Need For Systemic Change

We are a consumption-oriented society. The success of individuals, businesses and societies as a whole has historically been linked with growth in consumption since the industrial revolution. Supply and demand patterns, fuelled by current economic paradigms and continued population growth, put into serious question the long-term viability of continued growth in consumption-oriented behaviour. Even though currently there is a significant drop in global demand in response to the economic slowdown, consumption levels are expected to pick up again once economic activity resumes.

Two influences or triggers have the potential to shift behaviours: scarcity and value creation. Whether it is shortage of oil, water, financial liquidity or imagination, we are entering a new era where scarcity will influence the architecture of society and business. As business increasingly looks at meeting the future needs of consumers, there is a new shift towards value creation and innovative business models that extend available resources. This combination of "sticks" and "carrots" will result in increasing wealth and value for tomorrow's consumers and businesses in an environmentally sustainable manner.

These influences and triggers are not future events for deliberation; they represent the reality to be dealt with today – a journey on which leading innovators are already embarking. Consumer industry companies are experiencing an unprecedented period of change and volatility; even the underlying assumptions on which current business models were built are changing. Access to cheap resources and labour, predictable consumption growth, stakeholder expectations, and traditional business roles and accountabilities represent dynamic business conditions that require new thinking.

Globalization, developing market demand, resource constraints and broader environmental concern have created a higher level of inter-connectedness between business and society. The evolution of this global, interconnected model, combined with the volatile business conditions we face today, is challenging the business strategies of many companies.

Volatile input costs, greater societal expectations and evolving policy directions are possible early signals of a transition from a historically consumption-based model to one of sustainable production and consumption. Work through this initiative is intended to facilitate (and hopefully accelerate) the industry's movement through this transition.

The analysis, recommendations, and insights in this report are intended to represent a balanced view of risk and opportunity and highlight the need for companies to fundamentally rethink their value proposition. While it is unlikely that this work will serve as the tipping point for achieving sustainable growth, it is hoped that it will serve to accelerate industry's understanding of the key issues required to shift environmental concerns into the core of business.

The long-term trends of resource scarcity along with rising consumer markets in emerging economies will endure the current economic crisis, and so it is critical not to allow the urgent overtake the important. Much as business adapted quickly to globalization, the challenges of sustainability present an opportunity for new investments, new businesses and new business models. Collaborative innovation and a common understanding can increase momentum towards a new future for consumer industries.

MACROECONOMIC VIEW OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND

It is useful to look first at the economic elements that are shaping the argument for sustainability.

Globalization

Until the current global economic crisis, the world economy had grown for 20 years at a pace unprecedented in economic history. Unlike previous economic cycles, this growth was driven by rapid development in emerging economies, allowing many of them to narrow the historic gap with the developed world. It also enabled hundreds of millions of people to move from poverty into a new global middle class with material disposable income.

The primary cause of this growth was the integration of several major emerging countries into the global economy – China, India and Russia, among others, went from self-sufficient economic policies to embracing globalization. This meant freer movement of goods, capital and even people across international borders. It also marked the adoption of market-oriented policies, the end or reduction of internal and external trade restrictions, a reduction in subsidies and price controls, and even the encouragement of entrepreneurship.

This economic growth was additionally driven by a number of specific events: the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, privatization trends of the 1980s and 1990s which started in Margaret Thatcher's United Kingdom, "demonstration effects" of the success of market-oriented policies in developed countries, and success of export-oriented policies in the newly industrializing countries of East Asia.

These changes had a huge impact on the larger global economy. With roughly a billion new workers, globalization put downward pressure on wages and costs – and also downward pressure on prices. This contributed to the low inflation of the past 20 years and increased purchasing power globally. Those billion new workers also became a billion new consumers in the global economy. This increased the size of the market into which global companies could sell and also contributed to their efficiency gains.

Globalization, it seemed, was a very good thing. Some, however, have now suggested that the benefits of globalization are waning and costs are increasing, signalling perhaps that the era of low inflation is coming to an end. Nevertheless, there are, and will continue to be, consequences to globalization.

First, and most notably, the huge increase in demand in emerging countries has put upward pressure on global prices of commodities such as petroleum and many types of food and minerals (Figures 1 and 2). This has caused redistribution of global income, rising inflation and, in the case of food commodities, potential hunger. The recent drop in commodity prices is in response to a dramatic decline in economic growth globally. When economic activity begins to pick up again, so will the demand forces that are expected to drive up the commodity prices.

Second, globalization has contributed to increasing income inequality in developed countries. The increased supply of low-wage labour has reduced the demand for such labour in developed countries, thereby increasing the gap in pay between skilled and unskilled workers. This has given some basis to protectionist sentiment in developed countries.

Third, rapid economic growth in emerging countries has placed enormous pressure on the physical environment. Pollution in many emerging countries has become exceptionally bad and is already adding to public health costs and reduced life expectancy. In China, it has been estimated that a "Green GDP", which incorporates the health and social costs of the environmental degradation, ends up costing 3% of China's 2004 economic output – more than half a trillion yuan6. Environmental damage is often exacerbated by subsidies to food, fuels and energy use designed to create jobs, increase consumption and encourage economic growth.

It is estimated that one third of China's emissions are due to exports.7 Can the global economy continue to reap the enormous benefits of globalization while simultaneously dealing with the increasingly evident environmental and social costs? Society wants to sustain economic growth and lift billions more out of poverty, especially given that we will have one billion more consumers by 2020. They will expect to drive cars, travel by airplane, buy major electric appliances, and live in larger homes with air conditioning8,9. But we cannot afford to be as inefficient in the future in how we use resources and create waste as we have been in the past. We need to create new technological and management approaches, and entire new ways of doing business.

The Rise of Washing Machines in India

As women's roles have changed in Indian society and as the middle class has grown, washing machines have increasingly found their way into Indian homes. The washing machine industry grew by 22% in 2007, with sales of approximately 2.2 million units. The fully automatic category is particularly attractive to manufacturers and retailers because of its 40% growth rate in 2007. One large consumer electronics company has introduced a US$ 66 washing machine that caters to the unique preferences of Indian families by eliminating the drying cycle and also programming the machines to automatically resume the washing cycle after power returns from an outage.

As appliance manufacturers refine their product offerings and marketing activities, more and more middle class Indians will likely purchase washing machines, which will have significant impact on the environment. Almost every washing machine replaces hand-washing of clothes, requiring more water and more energy. There are opportunities as well, as countless hours of women's time will be liberated, offering a potential to increase economic output and productivity.

By 1940, 60% of the 25 million wired homes in the United States had an electric washing machine. By contrast of scale, India currently has over 100 million homes with televisions, and washing machines are rapidly catching up. In 2008, the University of Leeds created a washing machine that uses only a cup of water to carry out a full wash. The machine leaves clothes virtually dry, and uses less than 2% of the water and energy otherwise used by a conventional machine. The challenge that presents itself is how to embrace the lifestyle aspirations of these new consumers, while incorporating the next practices and technologies the world has to offer in the interest of the local and global environment.10

With increased information flows and greater transparency brought about by the spread of information technologies, the rising middle class will be perhaps less tolerant of societal failures. They will likely rebel against environmental pollution, be more attentive to the health and safety of the products they purchase, and be more focused on issues of public health and societal well-being in general. Thus, a process of globalization that does not address these issues will likely be deemed a failure not only to policy-makers, but by consumers as well.

Consumption patterns

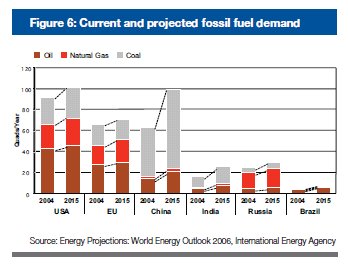

Historically, energy and resource use have been strongly coupled with economic and population growth. In the coming years, a disproportionate share of both economic and population growth will take place in developing countries as their economies strive to catch up with traditionally Western technology and lifestyles. Figures 3 and 4 show the projections for population growth and GDP growth for key economies. As these economies grow, consumer markets will rise rapidly as a result – as will consumer spending, which will rise as a share of GDP in many emerging markets, especially China.

As disposable income continues to increase, traditionally exporting economies like China will likely shift away from growth based on exports and towards growth based on domestic consumer spending.

Figure 5 compares consumer spending as a percentage of GDP and indicates the current gap between developed markets and emerging markets. This variation in consumer spending as a percentage of GDP will converge as the economies of the emerging markets grow further and mature. Note that the drop in consumer spending as a percentage of GDP for China in the last decade confirms that its GDP growth is not the result of growth in local consumption; however, this will change as China's middle class expands further.

As consumption growth takes place, the number of households moving from poverty to middle class will rise faster than the growth of the economy itself. When households grow out of poverty towards a new middle class with disposable income, the resource intensity of consumption – including food, energy, and raw materials – increases dramatically.

Thus, as emerging countries grow rapidly, the corresponding demand for basic resources – such as water, food and energy, as discussed below – also rises rapidly.

Water

Water security is the gossamer that links together the web of food, energy, climate, economic growth and human security challenges that the world economy faces over the next two decades. In many places around the world, water has been consistently under-priced, and has been wasted and overused as a result. Stocks of groundwater have been unsustainably depleted at the expense of future water needs. In effect, the world has enjoyed a series of regional water "bubbles" to support economic growth over the past 50 years or so, especially in agriculture. A number of these regional water bubbles are now bursting in parts of China, the Middle East, south-western US and India; more will follow. The consequences for regional economic and political stability will be serious.

From 1900 to 2000, global freshwater withdrawals grew ninefold against a population increase of factor four.11 According to the OECD, 2.8 billion, or 44%, of the world's population lives in areas of high water stress. This figure is expected to rise to 3.9 billion by 2030 under a business-as-usual scenario. If present trends continue, the livelihoods of one-third of the world's population will be affected by water scarcity by 2025, and could impact annual global crop yield to the equivalent of losing the entire grain crops of India and the US combined (30% of global cereal consumption)12.

With agriculture remaining a thinly-traded good, gains from trading so-called "virtual" water are limited. Agriculture as a share of exports in international trade decreased from 46% in 1950 to 9% in 2000. Changes in the geopolitical landscape will start to occur, as water-scarce countries seek their own water solutions. The global water forecast for the next two decades, if no reform actions are taken, is chilling; water scarcity will have a profound effect on global and regional systems, whether from an economic growth, human security, environmental or geopolitical stability perspective.

Food

Food production needs to rise by 50% by the year 2030 to meet the rising demand, according to a speech by Ban Ki-moon, calling on world leaders to increase food production and revitalize agriculture to ensure long-term food security.13

When households in emerging economies enter the middle class, they often shift from grain-based diets to diets dominated by foods that are more resource intensive such as meats, fruits and fresh produce. Given, for example, the large grain requirements for meat production, this leads to a disproportionate increase in the demand for grain, one factor affecting grain prices in recent years.

Additionally, the dynamics of food are inextricably linked to water use, as more than 70% of global freshwater withdrawals are used for agriculture,14 but inefficiencies in water use are high. Traditional irrigation, in most water-scarce countries, consumes only a fraction of the water it withdraws (about 50%); the rest is wasted or evaporates. Trade is also a complicating factor, and as society looks to biofuels and biomass for a solution to energy security, food supplies are likely to be affected. Domestic reform of water for agriculture is therefore urgently required in many water-stressed countries to produce "more crops with fewer drops". Engaging in global trade can also help countries to manage water security issues, but the global trade system for agriculture is outdated and in urgent need of reform. Systems thinking will be required to ensure that strategic long-term solutions are developed and implemented.

The volume of food production depends on a number of key factors – market pricing, protection of private property rights for farmers, availability of energy and water, cross-border trade, and impacts of climate change. Despite advances in agricultural technologies and land productivity, most of these factors augur low increases in food production in developing economies.

Long-term economic growth will result in continuing increases in the demand for grain and other agricultural commodities, creating upward pressure on food prices, despite the current recession. To feed tomorrow's consumers, there will be a need for freer trade, transparent pricing, encouraged investment in agricultural infrastructure, and more efficient use of the food that is already grown.

Energy

Today, energy usage is inefficient in many emerging markets, as well as in most of the OECD with the notable exception of Japan. Although developed nations may use more energy per capita, many developing nations use more energy per dollar of GDP. Using the most recent available data, the US (not generally the world's role model on efficient energy policy), is nearly five times more efficient than China in terms of energy consumed per dollar of GDP.15

These inefficiencies are often the result of subsidies, which discourage conservation and investment in efficiency,16 creating, in many cases, an unsustainable economic burden while exacerbating environmental damages. Energy subsidies in the 20 largest non-OECD countries reached US$ 310 billion in 2007. In the past, efforts to change such policies have been politically very unpopular; meaning, it is often difficult to shift towards market pricing of energy. Still, such pricing of environmental and social externalities is a necessary ingredient in shifting to clean energy supply and more efficient use of all energy.

In coming years, energy demand is expected to grow rapidly, especially as the effects of higher prices are not permitted to influence demand, often the case for energy used in transportation. Energy supplies will rise, although not necessarily commensurately with demand, in part because many countries with large potential supplies of energy are not actively encouraging investments in new capacity. The lack of encouragement for efficient energy use and demand-side management will compound supply shortfalls. This gap will lead to long-term increases in energy prices worldwide, despite current oil prices reflecting the economic downturn. If unregulated, this higher energy usage will likely drive continued price volatility and have negative effects on both business and the environment.

While energy demand increases globally, the US and EU will be simultaneously seeking to improve energy security. Energy policy decisions have strong connections to water, climate and food security policy, which can spin negatively or positively, and energy policy must take into account these interlinkages. To add a level of complication, domestic energy security can be seen as a decision to switch from relying on foreign oil to relying on domestic water. Fast-growing economies, especially in the Middle East and Asia, will likely allocate less water to agriculture over the next two decades and more to the growing demands of their urban, energy and industrial sectors. Under business-as-usual, water consumption for energy production is expected to grow by as much as 165% in the US and by as much as 130% in the EU over the same period, with serious consequences for water and food security.

The business imperative

Considering that resource prices have recently dropped dramatically, many business and political leaders may wonder why they should now bother with investing in resource efficiency. The current drop in resource prices is related to extreme weakness in demand given the downturn in the global economy, and many leading economists expect the global economy to begin recovery by the end of 200917. Once a sustained recovery is under way, it is likely that resource prices will rise quickly. Investments in efficiency can begin to pay off immediately and will position a company better as the global economy recovers.

Resource prices are likely to rise even higher and remain more elevated than in the past. If improperly addressed, policy decisions for resource security could lead to resource crises or even collapse. Business and governments will need to act together to ensure systemic solutions are put in place for the long term. Additionally, changes in pricing and the perception of environmental risk will likely change consumer behaviour, especially in developed countries.

Consumer industry businesses can act preemptively to meet such uncertainties by making some fundamental and mutually reinforcing changes such as:

- Investments in improved efficiency of resources

- Diversification of resource sourcing

- Changes in packaging and waste management

- Changing supply chain patterns to minimize transport costs

- Efforts to emphasize environmentally positive actions in brand positioning

To address these challenges and to avoid an escalation of personal interests at the expense of public goods, there is a need to have a clearer view of shared resources and interests. In game theory, this is referred to as the Prisoner's Dilemma, while in environmental circles it is commonly known as the "tragedy of the commons", in reference to a 1968 paper by ecologist Garrett Hardin.18 Companies across different sectors will need to work together to shift the boundaries of their thinking from single companies and products or lifecycles to systems and interlinkages along the whole value network and beyond.

Consumer response

Consumers play a big part in the calculus, especially since they tend to respond to economic incentives more than moral arguments. Looking at recent history, it will primarily be higher resource prices that lead to changes in consumer behaviour. Businesses tend to respond to consumers – if consumers change, then businesses will change. The challenge for business is to know when best to anticipate consumer behaviour and lead accordingly, and when to follow existing trends. The complexity of this dilemma from a sustainability standpoint is highlighted in the struggles of the North American automotive industry in recent months.

Looking forward, it is likely that permanently higher commodity prices will alter consumer behaviour in favour of lower energy consumption, fewer material purchases, and more efficiently grown food. This happened before in the 1970s, when consumers shifted to smaller cars and more energy-efficient homes. Similar shifts in consumption patterns are likely to happen again, only permanently this time, reflecting that the world is a very different place than it was 30 years ago. When oil prices spiked in 1973 and 1979, global demand decreased by 2% and 7%, respectively. By contrast, during the unprecedented oil price increases in 2008, global demand continued to rise, driven in part by demand in China and India.19

While the degree to which consumer and business behaviour shifts will depend largely on regulatory policies, farsighted companies need to help shape political will and consumer opinions. Ultimately, there is a common benefit in acting with long-term interests – for the consumer, business and government.

To read this document in its entirety please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.