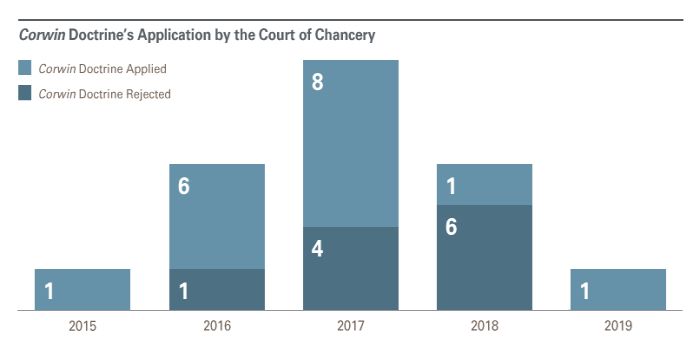

The Delaware Supreme Court's 2015 decision in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC1 fashioned a powerful defense in post-closing money damages cases for boards of directors by finding that business judgment deference applies where the challenged decision was approved by a majority of disinterested, fully informed and uncoerced stockholders, so long as there is no conflicted controlling stockholder present (the Corwin doctrine). The Corwin doctrine, in conjunction with other Delaware law developments during the same time period that made pre-closing injunctions in change of control transactions more difficult to secure (C&J Energy Services, Inc. v. City of Miami General Employees' & Sanitation Employees' Retirement Trust),2 and raised the bar for disclosure settlements (In re Trulia, Inc. Stockholder Litigation),3 was thought by some commentators to have swung the pendulum in defendants' favor. As the chart below demonstrates, the Corwin doctrine enjoyed a strong start resulting in many dismissals. That trend, however, reversed course in 2018.

Corwin Trends

The rise in cases where the Court of Chancery declined to apply the Corwin doctrine begs the question, why the change in fortune? The Corwin doctrine was applied only once by the Court of Chancery in 2018 to dismiss an action, and the court declined to apply the doctrine in six other cases. Four of the six decisions declining to invoke the doctrine found the disclosures issued in connection with the transaction insufficient for Corwin to apply.4 The two remaining Court of Chancery decisions declining to invoke the doctrine in 2018 did so based on the pleading-stage presence of an alleged conflicted-controlling stockholder.5 While each decision declining to invoke the Corwin doctrine turns on the unique facts presented, one potential reason for the changed dynamic in 2018 is that the plaintiffs' bar has recalibrated its approach and found increasing success by using documents obtained pursuant to Section 220 demands (or appraisal litigation or other discovery mechanisms) to defeat the application of the doctrine based on alleged inadequate disclosures (which have been the predominate basis for Delaware courts finding the doctrine inapplicable). Given the lack of meaningful pre-closing injunction risk to force corrective disclosures, boards and their advisors face a self-imposed burden to assess whether the disclosures issued will allow the Corwin doctrine to apply.

Analysis of Recent Decisions

A number of decisions in 2018 relied on Section 220 documents (such as board minutes or emails) obtained prior to the plenary action, and such documents played a role — or as the Supreme Court described in one case a "crucial" role — in avoiding dismissal under the Corwin doctrine. This seemingly was spurred on by a December 2017 decision, which contemplated the use of Section 220 to obtain company books and records to craft pleadings to defeat the Corwin doctrine at the pleading stage.6

Most interesting in 2018 are the two Delaware Supreme Court decisions regarding the Corwin doctrine. Previously, all appeals of dismissals pursuant to the doctrine resulted in short affirmances. However, in 2018 both Corwin doctrine appeals resulted in reversals by the Delaware Supreme Court for inadequate disclosures.

The Supreme Court's decision in Morrison v. Berry7 provides a potential roadmap for plaintiffs to attack the application of the Corwin doctrine based on disclosure issues. In Morrison, the plaintiff successfully used a "crucial" email produced in Section 220 litigation to raise a material disclosure claim. In reviewing the "crucial" email, the Delaware Supreme Court placed side-by-side in a chart the email and the relevant portion of the disclosure document and concluded the email demonstrated that the disclosure document contained a "material omission" regarding the company founder's agreement to roll over his equity interest. In reversing the Court of Chancery's dismissal under the Corwin doctrine, the Supreme Court emphasized the case "offers a cautionary reminder to directors and the attorneys who help them craft their disclosures: 'partial and elliptical disclosures' cannot facilitate the protection of the business judgment rule under the Corwin doctrine."8 The case is now moving forward in the Court of Chancery.

Similarly, in Appel v. Berkman,9 the Supreme Court reversed a dismissal under the Corwin doctrine because plaintiffs adequately pleaded that the stockholders' decision to accept a tender offer was not fully informed. Critical to this finding were board minutes produced pursuant to Section 220. The disclosure document omitted why the target company's chairman, founder and largest stockholder, whom the court described as "a 'key board member' if ever there were one," had abstained from supporting the merger. According to board minutes obtained pursuant to Section 220, this key board member abstained because he was disappointed with the price and management "for not having run the business in a manner that would command a higher price," and he did not think it was the right time to sell the company. Yet the disclosure document simply said that the chairman had abstained from the vote to approve the tender offer and had not yet determined whether to tender his shares, omitting his reasoning. The Supreme Court held that the failure to disclose the key board member's reason for abstaining, under the circumstances present in the case (including partial disclosures regarding the sale), rendered the disclosures issued "materially misleading."

In contrast, the two most recent Corwin dismissals do not appear to have involved books and records secured via Section 220. In English v. Narang,10 the only case so far in 2019 to address Corwin, the Court of Chancery applied the Corwin doctrine and dismissed a stockholder challenge. Plaintiffs in English sought to avoid dismissal by arguing, among other things, that the disclosures issued in connection with the transaction were inadequate. In rejecting this argument, the court addressed various disclosure challenges regarding financial projections, post-closing employment arrangements and alleged financial advisor conflicts and relied heavily on the contents of the disclosure documents themselves to conclude that each alleged deficiency failed as a matter of law. For example, with respect to the alleged financial advisor conflicts, the court rejected the disclosure challenge because (1) the fees earned, (2) the contingency portion of the fees and (3) the past work performed by the financial advisors were fully disclosed. The English decision is currently on appeal. Similarly, in In re Rouse Properties, Inc.,11 the only 2018 decision applying the Corwin doctrine to dismiss an action, the court rejected various disclosure challenges relying heavily on, among other things, the proxy statement's summary of the work the financial advisor performed, its potential conflicts and the projections it relied upon and rejected requests for greater "particulate detail."

Based on these rulings, one observation for the shift in results under the Corwin doctrine is the increased use of documents plaintiffs secure pursuant to Section 220 to plead disclosure claims. These cases show that accurate disclosure in connection with fundamental transactions is critical for deal planners and practitioners to secure the protections of the Corwin doctrine. The application of the Corwin doctrine can be defeated at the pleading stage through the use of documents obtained via Section 220 prior to a motion to dismiss, where such documents raise a material omission or create a material conflict with the disclosures issued in the transaction. Delaware courts will carefully review the challenged disclosures to determine whether a deficiency exists preventing the application of the Corwin doctrine, and directors and their counsel documenting the transaction must use care in ensuring that disclosures issued are consistent with corporate documents and communications. Given the lack of meaningful pre-vote injunction litigation after C&J Energy and Trulia, and now the Section 220 tactic plaintiffs have used to gain traction, companies, their boards and their advisors need to scrutinize disclosures closely for completeness and accuracy.

Takeaways

- While Corwin remains a

potentially powerful defense tool, the trend has been close

judicial examination regarding the adequacy of disclosures when the

Corwin doctrine is raised as a defense.

- Only one Court of Chancery decision in 2018 invoked the Corwin doctrine to dismiss an action, and the Corwin doctrine was found not to apply in the six remaining cases where raised by defendants.

- In both cases where the Delaware Supreme Court addressed dismissals under the Corwin doctrine in 2018, the court reversed and remanded the cases after finding inadequate disclosures.

- To best position a Corwin doctrine argument in post-closing litigation, companies, their boards and their advisors must pay attention to disclosure obligations before a stockholder vote because pre-closing challenges to disclosures seeking preliminary injunctive relief are now rare.

- Boards of directors should use particular care and consult with their legal counsel to ensure that material disclosures issued in connection with a transaction are supported by (and do not conflict with or omit material information from) contemporaneous corporate records.

- As the Delaware Supreme Court stated in Morrison, circumstances where disclosures conflict with or omit material information from contemporaneous corporate documents and communications offer "a cautionary reminder to directors and the attorneys who help them craft their disclosures: 'partial and elliptical disclosures' cannot facilitate protection of the business judgment rule under the Corwin doctrine."

Footnote

1 125 A.3d 304 (Del. 2015).

2 See C & J Energy Servs., Inc. v. City of Miami General Emps.' & Sanitation Emps.' Ret. Trust, 107 A.3d 1049 (Del. 2014).

3 See In re Trulia, Inc. Stockholder Litig., 129 A.3d 884 (Del. Ch. 2016).

4 In re Xura, Inc., Stockholder Litig., 2018 WL 6498677 (Del. Ch. Dec. 10, 2018); In re Tangoe, Inc. Stockholders Litig., 2018 WL 6074435 (Del. Ch. Nov. 20, 2018); In re PLX Tech. Inc., Stockholders Litig., 2018 WL 747180 (Del. Ch. Feb. 6, 2018) (Order); Kenneth Riche v. James C. Pappas, et al., C.A. No. 2018-0177-JTL (Del. Ch. Oct. 2, 2018) (TRANSCRIPT).

5 In re Hansen Med., Inc. Stockholders Litig., 2018 WL 3025525 (Del. Ch. June 18, 2018); In re Tesla Motors, Inc. Stockholder Litig., 2018 WL 1560293 (Del. Ch. Mar. 28, 2018).

6 See Lavin v. West Corp., 2017 WL 6728702, at *9-10, 14 (Del. Ch. Dec. 29, 2017).

7 191 A.3d 268 (Del. 2018), as revised (July 27, 2018).

8 Id. at 272 (emphasis added).

9 180 A.3d 1055 (Del. 2018).

10 2019 WL 1300855 (Del. Ch. Mar. 20, 2019).

11 2018 WL 1226015 (Del. Ch. Mar. 9, 2018).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.