On October 1, 2018, Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster of the Delaware Court of Chancery issued a 246-page post-trial opinion in Akorn, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi AG, C.A. No. 2018-0300-JTL, that denied the seller's (Akorn) request for specific performance to force buyer (Fresenius) to close a merger between the two companies. Following an expedited trial, the court found that Fresenius had validly terminated the merger agreement as a result of the failure of conditions to the merger agreement relating to the accuracy of Akorn's representations, Akorn's compliance with its covenants and the existence of a material adverse effect (MAE) on Akorn. The Akorn opinion is notable for several reasons, including that:

- It is the first post-trial opinion from the Court of Chancery finding the existence of an MAE and the first opinion in Delaware finding, after trial, that an acquiror could appropriately terminate a public company merger agreement in part because of an MAE;

- It provides important guidance about how MAE provisions will be construed under Delaware law, and the types of necessary facts and circumstances that would constitute a breach under what the Court of Chancery described as "customary" MAE language; and

- It offers detailed commentary on how the Court of Chancery will interpret other aspects of a merger agreement between sophisticated commercial parties, including customary phrases in merger agreements such as "in all material respects" and "commercially reasonable efforts."

At points, the opinion is a virtual textbook on M&A agreement drafting principles, MAE provisions, common merger agreement representations, conditions and termination rights, as well as other common terms and concepts found in merger agreements. At 246 pages, it is believed to be the longest written opinion in Court of Chancery history. While the decision is expected to be appealed, the trial court opinion provides a trenchant analysis in an area rarely explored by the Delaware courts.

While the decision is expected to be appealed, the trial court opinion provides a trenchant analysis in an area rarely explored by the Delaware courts.

The following is a high-level summary of the opinion; companies should consider consulting with counsel on how the Akorn decision impacts the negotiating and drafting of agreements, and how best to protect their interests in light of the ruling.

* * *

By way of background, the court found that Akorn, a generic pharmaceutical company, was confronted with serious, pervasive "data integrity" issues, which included submitting falsified product data to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), yet did nothing to meaningfully address such issues until Fresenius disclosed its concerns to Akorn and began conducting its own investigation after receiving multiple anonymous whistleblower letters post-signing. According to the court, Akorn subsequently misled the FDA in meetings it sought about the data integrity issues. In addition, the court found that Akorn's business "fell off a cliff" two days after its stockholders approved the merger. The initial revenue miss of more than 25 percent was followed by a sustained decline in Akorn's business. This led to general MAE issues as well as regulatory covenant breaches and more specific "regulatory MAE" issues.

As the court explained, Fresenius offered Akorn a chance to extend the outside date to allow for further investigation of the issues, but Akorn declined. Fresenius then gave notice that it was terminating the merger agreement because of (i) breach of regulatory representations and warranties that could reasonably be expected to have an MAE (the Bring-Down Condition); (ii) material breach of a covenant to operate in the ordinary course of business (the "Ordinary Course Covenant" and the "Covenant Compliance Condition"); and (iii) the right not to close once the outside date passed (two days after the notice was provided) because Akorn had suffered an MAE (the General MAE Condition).

The court found after trial that Fresenius proved that Akorn failed to satisfy the Bring-Down Condition because Akorn represented that it was in full compliance with all of its regulatory obligations. Similarly, Fresenius proved that Akorn failed to satisfy the Covenant Compliance Condition because Akorn failed to "use its ... commercially reasonable efforts to carry on its business in all material respects in the ordinary course of business." The court found that each of these conditions failed because of the pervasive and serious regulatory issues (which themselves were so severe that they constituted a regulatory MAE), and that Fresenius had a right to terminate the merger agreement under either or both because they could not be cured before the outside date and Fresenius was not in material breach of the merger agreement itself. In addition, the court found that the "sudden and sustained drop in Akorn's business performance constituted a general MAE," which allowed Fresenius to terminate the merger agreement once the outside date had passed.

General MAE

In its analysis of the general MAE claim, the court provided a thorough explanation of MAE clauses generally, including how they are typically drafted and how they allocate risk. Turning to the "customary" language of the general MAE provision in the merger agreement, the court largely followed the language in Hexion Specialty Chemicals, Inc. v. Huntsman Corp., 965 A.2d 715 (Del. Ch. 2008), noting that any predicate decline in business performance should be "measured in years rather than months." However, in a footnote, the court acknowledged commentator and extra-Delaware authority advocating for shorter durations for financial buyers.

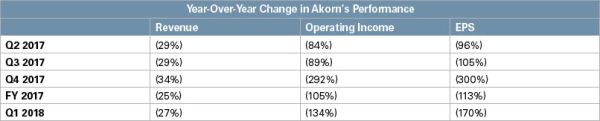

Recognizing that it is a fact-specific inquiry, the court grounded its finding that the decline was "durationally significant" in five straight quarters of decline that showed "no sign of abating" and could not be attributed to industry decline or other MAE exceptions in the merger agreement (as reflected in a chart offered by the court, recreated below):

The court rejected an argument from Akorn that Fresenius essentially assumed the risk of any potential issue for which Fresenius should have been on notice during due diligence. As the court explained, "[t]he strong American tradition of freedom of contract ... is especially strong in our State, which prides itself on having commercial laws that are efficient. ... Requiring parties to live with 'the language of the contracts they negotiate holds even greater force when, as here, the parties are sophisticated entities that bargained at arm's length.'" The court found that the decline in Akorn's business was unexpected, but even if it were foreseeable, the parties did not include within the MAE exceptions in the merger agreement any backward-looking language such as "matters disclosed during due diligence" and did not define MAE only to include "unforeseeable effects, changes, events, or occurrences." The court stated that the MAE language was forward-looking only.

Regulatory MAE

The court found "overwhelming evidence of widespread regulatory violations and pervasive compliance problems at Akorn" and found the regulatory issues to be both qualitatively and quantitatively material. The court estimated approximately $900 million in remediation costs, which equated to roughly 21 percent of the equity value implied by the merger agreement. While not free from doubt, the court found that 20 percent "would reasonably be expected to result in an MAE." As a result, the Bring-Down Condition was not met.

The court again rejected an argument that Fresenius assumed the risk of regulatory issues because it knew generally about Akorn's regulatory risk. The court found that such risk is precisely why Fresenius would want a representation in the merger agreement that it was in compliance, and that the contractual representation trumps any general knowledge of potential regulatory issues or questions about the extent of Fresenius' due diligence investigation. The court specifically rejected Akorn's argument (based on In re IBP, Inc. Shareholders Litig., 789 A.2d 1 (Del Ch. 2001)) that a broadly written MAE provision in this context "is best read as a backstop protecting the acquiror from the occurrence of unknown events" and thus implicitly incorporates a broad carve-out for any risks that the buyer may have known about or issues that the buyer identified or could have identified through due diligence. Once again, the court noted that the parties could have included such carve-outs from the contractual representation but did not.

Evaluating Fresenius' claim that Akorn failed to use "commercially reasonable efforts" to operate the business in the ordinary course, the court stated that Delaware case law did not seem to embrace the distinctions that transactional lawyers put on the various categories of "efforts." Citing the regulatory and process issues generally described above, the court also found that Akorn failed to use commercially reasonable efforts to operate in the ordinary course between signing and closing, and that such breaches were material. As a result, the court found that Akorn breached the Ordinary Course Covenant, and the Covenant Compliance Condition thus failed.

The court also noted that the covenants included customary language requiring Akorn to comply with its covenants "in all material respects." The court rejected Akorn's argument that "material" in this phrase equates to a material breach of contract under the common law. Instead, the court accepted Fresenius' argument that "material" is much closer to the materiality standard for federal disclosures, which requires that it be substantially likely that knowledge of the breach of the covenant would "have 'significantly altered the "total mix" of information,'" as compared to the buyer's reasonable expectations.

The court noted that Akorn could not cure the deficiencies before the outside date because it would take years to cure all of the issues. The court also found that Fresenius was not required to give Akorn an opportunity to cure before terminating because the issues were not "capable" of being cured before the outside date.

The court rejected Akorn's arguments that Fresenius materially breached the merger agreement. The court explained that "Akorn understandably has tried to cast Fresenius in the mold of the buyers in IBP and Hexion by accusing Fresenius of having 'buyer's remorse.'" In the court's view:

[T]he difference between this case and its forbearers is that the remorse was justified. In both IBP and Hexion, the buyers had second thoughts because of problems with their own businesses spurred by broader economic factors. In this case, by contrast, Fresenius responded after Akorn suffered a General MAE and after a legitimate investigation uncovered pervasive regulatory compliance failures.

The court found that Fresenius' actions to terminate the merger agreement did not breach a "reasonable best efforts" covenant to take the steps necessary to close because this condition did not require the parties to sacrifice their other contractual rights, and Fresenius' actions were taken in good faith in response to whistleblower allegations. The court also noted that, unlike other situations (referencing IBP and Hexion), Fresenius had raised its concerns directly with Akorn before filing suit, attempted to work with Akorn on these concerns and did not manufacture issues solely for litigation purposes. While the court noted that Fresenius only wanted to perform as required and "did not want to go the extra mile" after Akorn's business declined and the issues started coming to light, that was not enough to breach a "reasonable best efforts" covenant.

In contrast, the court noted that, for a week, Fresenius "contemplated" pursuing a path regarding antitrust approval "that could have constituted a material breach of a Hell-or-High-Water Covenant for antitrust approval had Fresenius continued to pursue it." For one week, Fresenius followed a Federal Trade Commission strategy that would have delayed approval by two months or more but ultimately decided to adopt the quicker path to approval when it received an unattractive offer for the asset at the center of the delayed path. By choosing this longer-timeline option for a week, Fresenius "technically breached" its covenant, but the breach was not material. Thus, Fresenius was not precluded from terminating the merger agreement as a result of Akorn's breaches.

Takeaways

While it remains to be seen how the opinion will fare on appeal, the Akorn opinion provides key takeaways for corporate negotiators as they structure merger and other agreements:

- Delaware courts remain committed to honoring the express contractual language of sophisticated commercial parties. The Akorn opinion suggests that the court will carefully construe the wording of merger agreement provisions (such as MAE provisions) and read them as written rather than rely on a general understanding of what such provisions typically mean or how they typically operate;

- Delaware law still requires a sustained and severe business decline, not attributable to general economic or industry factors, to find a general MAE, and a mere "blip" in financial performance should not be sufficient. On this point, the Akorn opinion is consistent with prior MAE cases decided under Delaware law;

- The court in Akorn appears to suggest that 20 percent of a company's total equity value (in terms of remediation and other costs associated with a regulatory covenant breach) could be a relevant threshold for determining whether an MAE has occurred;

- The court equated the phrase "in all material respects" not with the level of materiality required to excuse performance under a contract but with federal disclosure obligations, thus finding a breach "in all material respects" if the buyer's knowledge of a covenant breach would "significantly alter" the "total mix of information" when compared to the buyer's reasonable expectations;

- The court has signaled it may not recognize differences between the various "efforts" standards (i.e., "best efforts," "substantial efforts," etc.) in contractual agreements, though a "hell-or-high-water" standard ("all actions necessary") appears an exception; and

- Despite being the first Delaware Court of Chancery case to squarely find an MAE, and to permit a party to terminate a merger agreement based on the existence of an MAE, the facts that will lead to an MAE remain extreme. The decision suggests that future disputes over similar provisions will be very fact-intensive, and extreme facts will be required before the court will reach a similar conclusion.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.