Introduction

All mining operations disturb the natural environment. Companies that operate mines are obliged, to varying extents, to undertake work associated with the closure and decommissioning of their mines and rehabilitation of the impacted area. Closure provisions recognised in financial statements account for the future expense of undertaking this work1.

Closure provisions are becoming an increasingly important factor in the value of mining companies, representing approximately 7% of tangible fixed asset value across the sector in 20052. With various drivers impacting the quantum of these provisions, it is important that the information disclosed is sufficient to allow investors to understand fully a particular company’s position with respect to these liabilities. The quality and consistency of disclosure of such information in the sector is currently variable resulting in the opportunity for the sector to enhance the transparency of reporting.

Recognition of appropriate closure provisions and transparent reporting of them form an important element of the mining sector’s drive to articulate, in a more complete and consistent manner, its environmental and socio-economic goals and performance. This publication explores the numerous issues relating to closure provisions and puts forward suggestions for improving the transparency of reporting these liabilities in annual reports and financial statements to assist shareholders and wider stakeholders in their analysis and decision making.

It is often during corporate or asset transactions that these issues become a particular focus of attention. Having a robust and documented set of policies and processes which underpin the review and reporting of these provisions puts the vendor in a stronger position to protect value during the due diligence process.

The increasing significance of closure provisions

The total amount of closure provisions recognised has increased by some 2.7 times over the last six years from $4.2b to $11.4b, based on the sample of 27 major mining companies analysed (see Appendix 1). The incremental year on year increase in this total closure provision level has varied from:

- a rise of 11% from 2000 to 2001 provision levels;

- to an annual increase of between 28% and 31% between 2002 and 2004; and

- an increase of 12% from 2004 to 2005.

This indicates a potential easing of the year on year increase in 2005 following a three year period (2002 to 2004) of significant growth in the quantum of these provisions.

Consolidation within the mining sector has played some part in the increase in provisions within the sample of companies (although some of these transactions have been between companies within our sample set). However, taking the ratio (expressed as a percentage) of the closure provision against the tangible fixed asset value of each company moderates some of this effect. Analysis of these ratios over the period 2000 to 2005 (Figure 2) indicates that:

- the ratio for the full population of companies for each year (Figure 2) shows an increase in the "sector" annual ratio from 4.4% in 2000 to 6.9% in 2005;

- the majority (85%) of companies report an increase in the ratio of provisions to tangible fixed assets over the period;

- ratios for individual companies over this period range from 0% (ie, no provision recognised) to a maximum of 15.3%; and

- the largest increase in the provision to tangible fixed asset ratio over the period is 7.2%, with the largest decrease being 5.6%.

Whilst the cumulative tangible fixed asset value of the sampled companies increased between 2000 and 2005 by 75% (from $96b to $168b), the cumulative closure provision increased by 173% ($4.2b to $11.6b) over the same period.

The trend of increasing mine closure provisions over the last six years, in both absolute and relative (to tangible fixed asset) terms, is clear and has been driven by a number of factors which are discussed further below.

The drivers

A broad range of factors drive the levels of provision reported and accordingly contribute to the observed changes illustrated above. These factors can generally be characterised as:

- Macro (group and regional) level issues including:

1. Group portfolio – status and mix of operational and closed mines; 2. Financial reporting standards; and

3. Group policy – where this defines liabilities beyond that defined by accounting standards and mining/environmental legislation.

- Sub-macro (country and mine specific) level issues including:

4. Mine characteristics and location – particularly whether they are underground or open cut, and the sensitivity of environmental setting; 5. Mine closure legislation – in different operational jurisdictions; and

6. Financial guarantee arrangements – in various jurisdictions.

Macro level positioning factors

- Group portfolio

The aggregate closure liability within a company’s portfolio of mining operations at a point in time changes as:

- mine operations advance, creating new closure liabilities; and

- operators undertake contemporaneous rehabilitation works at active mining sites, and decommissioning and rehabilitation works at closed sites.

As the balance of this liability changes, so the provision will be adjusted to be consistent with the closure liability at the time of reporting.

- Financial reporting standards

- US GAAP/Canadian GAAP – the substantially similar US FAS 143i and Canadian CICA Section 3110ii standards on asset retirement obligations, together with US FAS 5iii on contingent liabilities;

- IFRS/UK GAAP – the substantially similar International Accounting Standard 37 ("IAS 37")iv and UK GAAP Financial Reporting Standard 12 ("FRS 12")v relating to provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets;

- South African GAAP – South Africa has no specific accounting guidance/standards on accounting provisions for mine closure or that specifically deal with accounting for mining companies so companies generally consider the guidance under IAS 37.

- Other GAAP – with respect to our sample of companies this is characterised by four companies that report under Brazilian, Chilean or Russian GAAPs4.

- similar and increasing ratios for those reporting against US and UK/IFRS GAAP;

- generally increasing ratios for Canadian GAAP reporters, with a decrease in 2005 (possibly due to the merger of the Noranda and Falconbridge in 2004);

- mainly decreasing ratios for South African reporters (which are generally transitioning to IFRS), with an increase in 2005;

- significantly increasing ratios for Russian/IFRS GAAP reporters over the last three years from a previous position of not recognising any provision; and

- marginally increasing ratios for the South American/US GAAP reporters.

- using third party contracting rates rather than internal cost rates to develop cost estimates; and

- applying a market risk premium, ie, the amount that would be required by a contractor to fix the price of the work that is to be undertaken in the future at current day prices.

- the required recognition of Conditional Asset Retirement Obligations ("CAROs") if the fair value of the liability can reasonably be estimated;

- guidance on when the fair value of AROs (and CAROs) can be reasonably estimated which substantially limits the circumstances under which fair value cannot be reasonably estimated; and

- prohibition on the use of management’s intent as the sole basis of determining whether the company can reasonably estimate the probabilities associated with potential dates and methods of settlement. It also requires the company to consider objective information in this determination, such as the company’s past practice, industry practice and the asset’s estimated economic life.

- Group policy

- Mine characteristics and environment

The nature and scope of mine closure activities can vary considerably across different mining operations. Some sites can be successfully reclaimed to a stable condition within a relatively short period from the end of the mine’s life, whilst others require long-term care.

This variation is driven by a wide variety of factors which at a macro level are determined by the physical characteristics of the ore body and sensitivity of the surrounding environment such as water resources and ecosystems.

Ore body characteristics

The large surface area impacted by open cut operations generally requires a more extensive and costly rehabilitation effort than that required for underground mines.

The type of mine, grade of ore being extracted, and efficiency of processing being employed to concentrate the ore, all have a significant bearing on the amount and type of waste materials being produced. This in turn determines the type and extent of waste disposal facilities requiring rehabilitation and nature and extent of any soil and water contamination requiring remediation. For example, the long-term management of acid mine drainage ("AMD") can be a significant cost.

The age of a mining operation may have a particular bearing on these issues where less efficient mining and processing techniques are being employed, and where historical management standards have been lower, leading to greater environmental damage.

Environmental setting

Mining operations located in environments where they can impact high quality water resources, local communities, fragile ecosystems and important landscapes incur additional cost in planning and management. This additional cost extends to the decommissioning and rehabilitation phases where the standards applied by the regulators are likely to be higher, with long-term commitments to post-closure maintenance and monitoring.

The location of a mine can also have important implications for the nature and scope of rehabilitation works undertaken due to meteorological conditions. Operations based in places such as the Amazon and Papua New Guinea have significant water control issues due to the high rainfall. These problems are then compounded by the particularly fragile ecosystems in these locations.

- Mine closure legislation

- the Chilean Ministry of Mining passed a modification to the mining safety regulations in 2004 requiring companies to submit rehabilitation plans within 5 years;

- the Peruvian Government also approved a new rehabilitation law in 2004; and

- the adoption of the EU Directive "on the management of waste from the extractive industries" (15 March 2006).

- Similar, relatively high annual ratios for companies whose operations include mines within the USA and for the three global companies10. The high ratios for the global companies are particularly driven by Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton, suggesting that the basis of provisioning in these two companies may be different from the others, due to:

- the application of more stringent closure and rehabilitation standards; and

- the application of a common global standard across the group, rather than adopting local standards in different operational jurisdictions (as discussed in the group policy section above).

- It is interesting to note that the greater than average increase in the ratio for the "global" companies in 2004 is consistent with the adoption of "closure standards" by BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto during 2004.

- Convergence of ratios for companies whose operations include those in Canada, Australia and South America. It is noted that whilst the ratios for South American and Canadian operations have increased significantly over the period, those for Australia have remained static.

- A significant increase in the annual average ratios of companies with operations in Russia, to a level similar to those for operations in Africa, whilst ratios for companies whose operations include mines in Africa have remained static.

- Relatively low average ratios for companies that have operations in India due to absence of specific legal obligations on mine closure, although the 2003/2004 ratios show a greater increase than in previous years resulting in some closing of the gap with the ratios in Russia and Africa.

- Financial guarantee arrangements

- scope of liabilities defined by local legislation and internal policy which a company is required to address;

- methodology utilised to estimate the costs associated with discharging the obligations;

- approach to modelling decommissioning and rehabilitation expenditure, often over periods of decades; and

- calculation of present values utilising inflation and discounting factors.

- Scope of the liability – information provided regarding the types of facilities and closure/rehabilitation work included within the provision, and the basis for the standard of closure/rehabilitation work against which estimates are prepared.

- Cost estimation process – information provided as to the process through which the provision is estimated and revised.

- Accounting treatment and form of reporting – accessibility of information with respect to the quantum of the overall liability and the nature of the accounting treatment applied.

- sites/facilities included in the provision;

- type of closure and rehabilitation works that are included within the cost estimates; and

- level/quality of closure and rehabilitation work that is required as a function of the environment in which the mine/facilities are located, national legislation and company policy.

- 33% report the undiscounted cost for the total liability;

- 21% indicate the period over which the liability is to be discharged and hence cost incurred;

- 8% present some sort of expenditure profile with time; and

- 25% report the discount rate applied in calculating the present value.

- decommissioning liabilities – which are recognised as a provision with a corresponding increase to the associated asset, depreciated over the life of the asset; and

- rehabilitation liabilities – which are recognised through accrual of the provision, the costs being charged to the income statement as a cost of production.

Provisions are recognised at the discounted net present value ("NPV") of the cost forecasts, as estimated by management or an independent party, for mine closure. The discount is unwound each year to account for the shorter period of time until mine closure, when expenditure will be incurred on closure works3. The discount factor applied by the company can have a significant impact on the provision because of the large number of years it is often applied over to reflect the period to mine closure.

The period to closure is determined based on modelling ore reserves and grades, and extraction rates. Accordingly, the estimation of these two parameters has an important bearing on the provisions recognised such that the net provision position at closure is representative of the full liability for decommissioning and rehabilitation.

The accounting standards against which mining companies report are also an important factor in the observed changes in the levels of provisions. Mining companies fall into a number of clear groups:

The ratios of provision to tangible fixed assets based on aggregating companies according to their financial reporting environment, (Figure 3) shows (in decreasing order of magnitude):

US/Canadian Standards

The impact of the introduction of FAS 143 (in the USA) and CICA 3110 (in Canada)5 is clear from the changes in provision to tangible fixed asset ratios for 2003 and 2004 respectively (Figure 3). It is also interesting to note the decrease in ratios for both groups in the following year. Prior to the introduction of FAS 143 in the US, a broad range of environmental liabilities (including those associated with mine closure) were accounted for under FAS 5. FAS 143, originally developed to account for the decommissioning costs associated with nuclear power stations, introduced the concept of Asset Retirement Obligations ("AROs"). AROs are defined as legal obligations associated with the closure, decontamination and removal of long-lived assets in all sectors, including mining. The transition from FAS 5 to FAS 143 has caused many companies to restate their closure provisions due to changes in both the quantum of estimated closure expenditure and the timing of the provision recognition. The main differences between these two standards, that have driven the observed changes in closure provisions, are summarised in Table 1 on the previous page.

Some mining companies now carry an ARO provision for mine closure (under FAS 143) and a separate "environmental" provision for remediation of contamination at sites (under FAS 5). The boundary between rehabilitation works included within the ARO and remediation works included in the "environmental" provision is not always clear. The differences between the two accounting standards, as discussed above, may also lead to some misunderstanding as to the basis of the different provisions.

The introduction of FAS 143/CICA 3110 has therefore not only caused mining companies to review their closure estimates, but in many cases to make fundamental changes to modelling these estimates such as:

The introduction of Interpretation No 47vi (FIN 47)6 in the US seeks to clarify various issues arising from the introduction of FAS 143, including:

These further clarifications are likely to promote some further adjustments to ARO provisions, and may account for the increase in the provision to tangible fixed asset ratios seen in 2005 for mining companies reporting under US GAAP.

International/UK Standards

UK FRS 12 and IAS 37 were both introduced in 1999 and have remained substantially unchanged since then. Despite this, however, there is a noticeable increase in the provisions for IFRS/UK GAAP reporting companies in 2004 (Figure 3). This may, in part, be due to changes in approach across a group promoted by changes within US/Canadian subsidiaries, but is also likely to be due to some of the further factors discussed in this paper.

It is noted that the International Accounting Standards Board ("IASB") published proposed amendments to IAS 37 (to be re-titled Nonfinancial Liabilities) in June 20057. Under these proposals entities would be required to recognise in their financial statements all obligations, unless they cannot be measured reliably. Uncertainty about the amount or timing of the economic benefits that will be required to settle a liability would be reflected in the measurement of that liability instead of (as is currently required) affecting whether it is recognised. This change would enhance financial reporting because some liabilities previously only disclosed in the notes to the financial statements will now be included in the balance sheet. Moreover, it would make the IFRS approach more consistent with that of US GAAP.

The evolution of accounting standards and the resulting changes in the nature and quantum of reported mine closure provisions, highlight the continued need for narrative information in annual reports which clearly describes the nature of accounting policies applied, and the effects of any changes to those policies.

In response to pressure from stakeholders concerning corporate responsibility, some companies commit to go beyond the minimum requirements of local legislation, for example by adopting a common standard across a group. This additional commitment may, in part, be driven by becoming signatories to international treaties, such as the International Council on Mining & Metals ("ICMM") Sustainable Development Framework Principles8. Another example in this area is the adoption of the Equator Principles9 by banks that account for some 80% of project loans globally. Under the Equator Principles, project financing in the mining and other sectors will include a common framework within which the social and environmental impact of a project will be assessed.

There is increasing recognition of the socio-economic impacts of mine closure, particularly where, in many cases, isolated communities have grown around and are dependent on the mine. One company, for example, reports a separate "social provision" to cover obligations for skills retraining and other community support activities. The definition of expectations and obligations in this area are likely to continue to increase due to a combination of enhanced legal requirements and continued stakeholder pressure. Careful consideration of these obligations is required to assess whether recognised provisions should account for this future expenditure.

It is interesting to note that BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto each adopted a "Closure Standard" in 2004 which applies to all their respective operations. These standards require the preparation and implementation of closure plans to a common standard, which are regularly reviewed and updated. The closure plans have to address the impact on both the natural and human environments and require cost estimates to be prepared and reviewed for each closure plan.

Clarity on the definition and application of a group’s standards to the operations within their portfolio, and how these relate to the forecast expenditure included within the provision, is important to understand and assess a company’s closure provisions.

Sub-macro level provisioning factors

In line with the ongoing enhancement of environmental protection legislation in the majority of jurisdictions around the globe, legislation that defines obligations for operators of mining facilities continues to be introduced and evolve at a significant pace, for example:

The EU Directive includes requirements to draw up closure plans for waste management facilities to ensure that closure operations form an integral part of the overall operational plan. Where not already addressed by member state legislation, the adoption of this Directive and transposition into member state legislation (by May 2008) will further define a company’s obligations associated with work programmes for, and costs of, mine decommissioning and rehabilitation.

Mining companies operate in a number of different jurisdictions around the world all of which specify varying levels of mine closure obligations. A consolidated closure provision, is reported by companies, giving no transparency as to the differing levels of provisions made for individual mining operations. As a proxy to the level of provisioning in different jurisdictions, Figure 4 illustrates the aggregated closure provision to tangible fixed asset ratio for each year for the group of companies which have operations in a particular geographic area.

The relative maturity and development of mine closure legislation in different areas of the globe is illustrated indicatively by the results shown on Figure 4 with some of the noticeable features being:

There is wide variation in the legal obligations associated with mine closure across different jurisdictions around the globe. It would appear, from the indicative analysis presented in Figure 4, that this variation is sufficient to drive significant differences in the levels of provision recognised by companies operating in these diverse areas. Gaining a clear understanding about whether provisions are based on local legal obligations or higher internal standards, and the extent of those standards, is, therefore, important in being able to assess a particular company’s reported provision.

Many governments have introduced requirements for financial provision arrangements which, in contrast to accounting provisions, guarantee the availability of funds for the decommissioning and rehabilitation of mine sites were the operator to default on its obligations. In many cases, these arrangements serve to define further the nature and quantum of liabilities, which in turn can influence the scoping and estimation of accounting provisions.

A recent study undertaken for the ICMM concludes that several jurisdictions have strengthened their legislation in respect of financial guarantee arrangements in recent years, including Botswana, Canada (the Yukon), Chile, Ghana, India, Peru, South Africa, Sweden and the United States. The proposed EU Directive on the management of waste from the extractive industries, as discussed above, also includes requirements for financial guarantee arrangements.

Calculating closure provisions

In the above sections we have discussed some of the drivers and the potentially large range of factors which influence the quantum of provisions recognised by mining companies for mine decommissioning and rehabilitation. This range of factors and management’s associated assumptions introduces significant uncertainty into the calculation of closure provisions. This uncertainty is illustrated by Rio Tinto which reports (in 2005) that the closure provision ($2.7b) could be up to 20% less (ie, $2.2b) through to 30% greater (ie, $3.5b) than reported. These influencing factors include the:

Current transparency

Given the complex interaction of the various factors (discussed above) which influence closure provisions, clear reporting of management’s approach and main assumptions is important to investors in understanding the basis of the reported provision.

There is a wide variation in the amount of information presented in Annual Financial Statements with respect to mine closure and rehabilitation provisions. Such disclosures range from a few short paragraphs in the notes to the accounts through to pages of narrative, typically seen in the Management Discussion and Analysis ("MD&A") sections of US/Canadian Annual Reports.

Analysis of the information provided by 2411 of the sample companies within their most recent (ie, 2005) Annual Report and Financial Statements is discussed in the following sections under three themes:

Scope of the liability

The cost estimates used as the basis for calculating a provision are themselves dependent on the scope of obligation/liability defined by regulators and/or the company. The scope of obligation can relate to the:

In only three of the 24 reports analysed is it made clear explicitly whether the provision reported relates to operational, closed, or operational and closed sites.

In the majority of reports (75%) there was little indication as to whether the provision relates solely to the decommissioning and rehabilitation of the mine, or whether it includes closure work related to associated sites occupied by waste, processing and refining facilities.

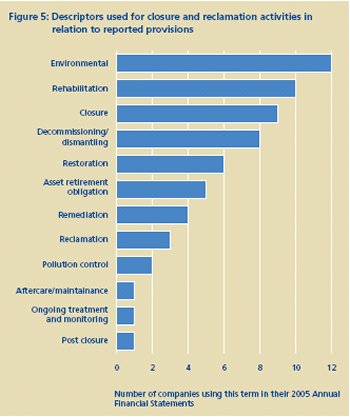

A wide range of terms is used to describe closure and rehabilitation activities, as summarised in Figure 5. Although these terms are all commonly used within the mining and other sectors, there are no standard definitions for the work that is undertaken under these descriptors and generally, with only a few exceptions, there is little definition of these terms when used in Annual Reports and Financial Statements.

The liability to undertake closure and rehabilitation works can be defined by legal obligations (as specified by local legislation in the county of operation) or by constructive obligations (created by the company). The majority of reports (80%) do not make the basis of the obligation clear (except in terms of general compliance with legislation). Although 20% of the reports are clear that the obligation is based on local legal requirements or the companies’ own internal standards, there is then no definition of the companies’ own internal requirements or confirmation that they are applied consistently to all operations.

Cost estimation process

The involvement of third party consultants in the preparation or verification of cost estimates for closure and rehabilitation works provides additional comfort on the accuracy of cost forecasts. However, the majority of reports (79%) do not explicitly disclose the source of cost data used to develop the provision. Two companies are notable in reporting that all/most of their cost data is produced by external consultants, whilst one company specifically reports that its provision is based on cost estimates generated by management.

Although some companies state that the liability and cost forecasts are reviewed regularly, only one third of the sample group reported the frequency of this review (which in all reported cases was annually). With the exception of two companies, no information was provided as to the management level at which this review was undertaken/approved.

With no information as to the undiscounted value of the total liability and the underlying cash flow forecasts, the reader is left uninformed as to the potential impact, particularly in terms of timing, that closure and rehabilitation expenditure might have on earnings. Information on these aspects is generally sparse as illustrated by the following:

Certain additional requirements have been added to the Canadian CICA 3110 standard, adopted for financial years beginning on or after 1 January 2004, which include disclosures of the key assumptions on which the carrying amount of the ARO is based, including the total undiscounted estimated cash flow, the expected timing of payment of cash, and the credit-adjusted risk-free rate at which the estimated cash flows have been discounted.

As noted above with respect to accounting standards, there are a number of terms/methodologies that are applied to calculate the costs associated with closure and rehabilitation, including "minimum", "best", "most likely", and "expected" values. Whilst the use of some of these terms and their definitions are described in the various applicable accounting standards, there is still room for confusion and thus an opportunity for companies to provide better definitions of the costing methodology adopted. US FIN 47 clarifies the various options available to calculate "fair value", of which the "expected value" option is expected to be the most widely used. Still, with a choice of methodologies under this system, information relating to the methodology applied would help the reader understand the level of sophistication and linkage with "market" rates that the estimates represent.

Accounting treatment and form of reporting

The immediate visibility of closure and rehabilitation provisions within financial statements is generally relatively poor, as they are largely only disclosed within the notes to the accounts (75% of our sample of reports). In the other reports, the provision is disclosed as a separate item on the consolidated balance sheet for the group.

The adjustments to provisions made year on year can often be significant and due to a number of different factors. However, three of the reports in our sample did not include an analysis of the adjustments made to the provision during the year. Where analysis is provided, the level of detail is generally sufficient to explain the reasons for the adjustments. However, there are a number of different terms/styles used in reporting these adjustments as illustrated in Figure 6.

It is clear within nearly all financial statements that, consistent with the various reporting standards, provisions are recognised in the period in which the liability is incurred, and that a corresponding value is added to the carrying value of the associated asset (assuming that there is one). The depreciation of the asset value is then based on a unit of production basis or straight-line basis over the life of the mine.

The basis of depreciation was not clearly documented in many of the reports. Both the above depreciation methods, and hence the rate of depreciation, are linked to the estimated ore reserve. However, no information was provided in terms of the assumptions and calculations used to estimate ore reserves in this respect.

A number of companies reported the different approaches to accounting treatment they use for:

Conclusions and recommendations

On the basis of our analysis covering a sample of 27 companies, we draw the following conclusions concerning mine closure provisions:

- Provisions recognised for closure and rehabilitation of mining facilities have generally increased over the last five years both in real terms and relative to the tangible fixed asset value of those companies included in our sample.

- There appears to be significant differences in the relative amounts of provisions (as compared to tangible fixed asset values) recognised when comparing companies on the basis of different financial reporting standards, and the different geographical areas in which they operate.

- Other factors, such as the enhanced response of mining companies to the corporate responsibility/sustainability agenda and the increasing use of financial guarantee mechanisms may also be influencing company’s policies and approach to closure provisioning.

- Notwithstanding the definitions established within various financial reporting standards, there remains opportunity for confusion between the use of terms and lack of definitive guidance (in some cases) as to the type of information to be disclosed. Given the wide range of variables that can impact management’s judgement in calculating closure and rehabilitation provisions, it is important that investors are able to understand the key assumptions, parameters and methodologies adopted by management in estimating the scope of work and costs associated with the closure of mining operations.

Accordingly, we believe that there is a general need for companies within the mining sector to provide clearer, more consistent and more transparent information on closure provisions, such that investors and other interested parties are better informed as to the scope of the liabilities and basis of the recognised provision.

We also recommend the application of several general principles concerning the disclosure of mine closure provisions (Table 2).

We recommend that, in the medium-term, efforts are made to develop a body of standards and guidelines to govern the competence of closure provision estimators and the processes applied in their work. It would appear appropriate that closure provision information included in annual reports should be sourced from appropriately qualified professionals, whether internal employees or external consultants.

Footnotes

- To avoid confusion, some standard terms are used in this publication with the following meanings:

- Closure – the cessation of operations at a mine site, but with no implication of any particular level of site clean-up.

- Decommissioning – removal of plant, equipment and infrastructure installed at the site during its operation.

- Rehabilitation – post-closure improvement of the site to a desired standard, but not necessarily returning the site to the state in which it existed prior to mining. It is understood to be synonymous with reclamation and restoration.

- Closure provision – the accounting provision recognised on a company’s balance sheet for future expenditure on decommissioning and rehabilitation work. This includes relevant Asset Retirement Obligations ("ARO") recognised by companies reporting under US/Canadian Generally Accepted Accounting Principles ("GAAP").

- The analysis in this paper is based on data extracted from the Annual Financial Statements reported by 27 mining companies (Appendix 1) for the period 2000 to 2005.

- It is recognised that part of the annual increase in the reported provisions is the unwinding of the discount to account for the passage of time to the point when the expense will be incurred.

Analysis of the impact of the unwinding of the discount (based on data from companies that report this as a separate annual adjustment over the six year study period) indicates that it is not significant to the general trends discussed in this paper.

- It is noted that the Brazilian GAAP reporter and one of the Russian GAAP reporters have transitioned to US GAAP and IFRS respectively during the period of analysis.

- FAS 143, in the USA, and CICA 3110, in Canada, became effective for financial years beginning after 15 June 2002 and 1 January 2003 respectively.

- FIN 47 is effective for financial years ending after 15 December 2005.

- These proposed amendments were subject to round table discussions in Q4 2006, with the issue of a revised standard expected in the second half of 2007

- The following companies are members of ICMM and have committed to measuring their performance against the ICMM Sustainable Development Framework Principles: Alcoa, Anglo American, AngloGold, BHP Billiton, Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold, Mitsubishi Materials, Newmont, Nippon Mining and Metals, Noranda, Pasminco, Placer Dome, Rio Tinto, Sumitomo Metal Mining, Umicore, WMC Resources, Xstrata. These Principles include, inter alia, commitments to:

- integrate sustainable development considerations within the corporate decision-making process;

- seek continual improvement of environmental performance; and

- contribute to the social, economic and institutional development of the communities in which a company operates.

- The Equator Principles, first adopted by ten international banks in June 2003, establish a framework for managing environmental and social risks in project lending. They consist of a set of guidelines based on environmental and social standards used by IFC.

- Anglo American, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto.

- Three of the companies in the original 27 companies analysed and discussed above have not produced 2005 reports as they have been acquired during 2003/04. As a result, these three have been omitted from the following analysis.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.