I enter a room filled with 20 notable business leaders, innovators and entrepreneurs. They've all been commended for their success, most of them with an annual growth rate in excess of 1,000%. Their LinkedIn profiles cumulatively reach 20,000 people, and their average number of contacts is 1,300 – 40% higher than the average CEO. Some of them work in software development, others in fuel cell technology. The range of perspectives, expertise and knowledge is wide, but they've all branched out as entrepreneurs. Everybody knows doing that is risky, and going up against the establishment does take some guts. J.M. Keynes is credited with saying "worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally." Indeed.

That's exactly the opposite of what these people have done. However, they all vary in expertise. This makes me think: what are the common factors in their success?

The network effect

The attendees stem from a wide array of industries, and their differences are significant. So I ask myself: what could they learn from each other and the conversations they have? I then realised, the differences in their businesses and personal backgrounds play to their advantage. I'm referring to network science, a field of study that seeks to analyse the nature of social groups and networks, the process of knowledge exchange, and the resulting benefits. But then again, we all know this. Networking is just all about talking to people, right?

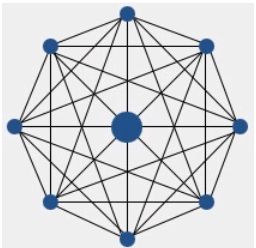

Let's dive into this in a different way, by taking an angle I'm hoping is new to you. But first, imagine this: people from one cluster – let's say your capability group in your company – meet up to build connections and exchange ideas. The node image of that would look like something like this:

One person, who is connected to all, presents back to the others, who are also connected to all. Any and all ideas and experiences that are deemed good or valuable by the group will probably be recognised as "good practice". Mindsets have similarities among the members of this group and ideas are readily adopted.

This is the type of cluster many of us operate and strategise in – to little avail.

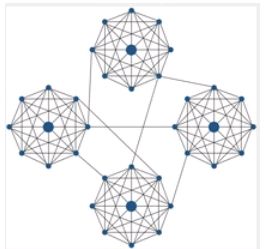

Now, imagine a similar situation, but with four clusters involved. Four groups that are completely independent of each other with regards to industries and backgrounds. Naturally, these groups will have different perspectives, viewpoints and ideas. The node image would look like this:

Any idea that is tested and proven by one of the groups may well prove detrimental to another – or vice versa. The point I'm trying to make here is that the more diversity you can bring to your perspectives and ideas, the more accurate your view of the world will be. In real life, the innovator's gladiator pit, an idea and its application are evaluated and consumed by infinite clusters. Therefore, when you test ideas across clusters, it makes the knowledge exchange effective, squared. This is quoted as one of key fundamentals to Steve Jobs and Apple's success, and is a key trait the Fast50 winners have in common. Very few of us operate in that type of network – and those who do reap benefit for themselves and others that most people fail to identify in the first place.

This is the essence of the new angle I was talking about above. As you progress to a more open network and have a more effective knowledge exchange, your roles and positions in any group become top class. In fact, in achieving this, your key objective should be to become an integrator or broker of information between these clusters – if you're able to bring numerous perspectives to the table, your value add will increase ten-fold. Having such an open network has even been proved to have a significant impact on your career success. You make yourself indispensable, not because of what and who you know, but because of the width in what and who you know. Then you realise that these connections' perspectives can be more appropriate than those currently in your team. It's like the saying "if you're the smartest person in the room, you're in the wrong room".

So what does this have to do with gathering the Fast50 Alumni one evening in May? It's about getting those clusters together, cultivating their connections and ensuring a useful knowledge exchange. This would benefit both yourself and others. For instance, Gav Winter (LinkedIn), MD of the software testing company The Test People, provided a thought-provoking point that is relevant for any consultant or service provider, myself included; "In client engagements, the delivery should define longevity in relationships, not the other way around." Success is rooted in how you deliver, not what you do to extend engagements.

As the Fast50 Alumni evening was coming to its end, I spoke to Henri Winand (LinkedIn), CEO of Intelligent Energy, a company which has fuel cell technology use in anything from telecom grids in India, cabs in London, even in your smartphone. Henri and I were looking at a 3D printer, which had been set up on the night to show people how the technology works. The printer was in the midst of printing an actual wrench. Curious, I started to wonder if an energy guru like Henri would have any insights on something as seemingly far-fetched as the world of 3D printing. I then asked: "Could you use 3D printing technology to print fuel cells?" Working in a company that has more patents than employees, Henri replied with confidence: "Sure, with time, why not?"

Open networks, applied.

Related links

https://twitter.com/TechFast50

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.