Capital adequacy goes strategic

The implementation of the FSA’s Individual Capital Adequacy Standards regime in the UK has far-reaching consequences for all stakeholders in the insurance industry. The "Use Test" in particular, which seeks to embed a firm’s capital adequacy calculations in its risk management framework, will bring prudential capital into the boardroom as a tool for shaping strategy. Deloitte’s Roger Jackson explores the benefits of the new regime and suggests that firms that get on board early will be at a distinct advantage.

The Individual Capital Adequacy Standards (ICAS) regime in the UK has now been in place for nearly a year and the challenge has moved from discussing the proposals to calculating the number. This is set to change over the next couple of years, to how to embed a firm’s capital calculations into their risk management processes; what the FSA calls the "Use Test". As we shall see, this article explores some of the potential consequences on key stakeholders of embedding this regime.

Stakeholders

Key stakeholders within the insurance industry in the context of capital requirements are:

- investors;

- insurers and reinsurers;

- policyholders;

- the regulator; and

- rating agencies.

Depending upon the stakeholder, the purpose of capital varies. Investors, enacted by the insurers and reinsurers that they invest in, focus on maximising post-tax profits given a certain level of capital (assuming that the level of capital is fixed). On the other hand, policyholders see capital as a measure of their security. The key to understanding the potential impact of the new regulatory regime, though, is to understand how the roles of the regulator and rating agencies interact with respect to capital.

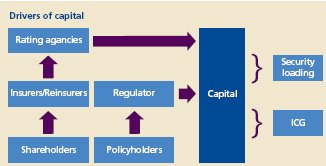

Drivers of capital

Rating agencies provide independent financial strength ratings, usually based on a qualitative and quantitative risk assessment of the firm, to give ‘an opinion as to the insurer’s financial strength and ability to meet its obligations to policyholders’ (AM Best). There are a number of users of such information, such as:

- policyholders, including individuals, corporations and insurers, who may themselves gain additional confidence from firms ratings;

- insurers, who want to ensure the credibility of their reinsurers; and

- analysts, who want to compare the financial condition of different companies potentially across different jurisdictions.

Some of the lowest ratings from the rating agencies refer to "under regulatory review" or "under liquidation", which usually infers that the firm is below the prudential minimum capital requirements. This means that other ratings imply a level of capital at least as large as the prudential minimum capital requirement. Indeed, most of the major rating agencies stipulate that firms require higher levels of solvency in order to be considered for higher rating grades. This creates a level of capital in excess of the prudential requirement, a security loading, that insurers and reinsurers have to achieve if they want to differentiate themselves publicly in relation to policyholder security.

Changes in prudential capital

Prior to the ICAS regime, minimum capital requirements were set via a formula in relation to premiums, or to claims if the ultimate loss ratio was greater than around 70%. However, these minimum capital requirements were recognised as being too low and so in reality the regulator required around two or three times the calculated minimum requirement. The exact level of prudential capital required depended on numerous other factors including qualitative information gained from discussions with the firm.

The FSA has four statutory objectives, namely to:

- maintain market confidence;

- promote public awareness;

- secure the appropriate degree of consumer protection; and

- reduce financial crime.

The objective to secure the appropriate degree of consumer protection is addressed within the ICAS regime by requiring insurers to assess the level and quality of capital so that there is no significant risk that they are unable to pay liabilities as they fall due. Guidance to what constitutes a "significant risk" stipulates a 99.5% confidence level, over a one-year time horizon on a Value-at-Risk (VaR) basis. The calibration of the FSA’s new formula-based capital requirement (the Enhanced Capital Requirement or ECR) used this basis, which was equated to a "BBB" Standard & Poor’s rating.

Stakeholder

- Shareholders/insurers and reinsurers

- Policyholders

- Regulator

- Rating agencies

Capital aims

- Maximise profit (on set level of capital)

- Security

- Policyholder security and market confidence

- Policyholder security (relative benchmarks)

By encouraging firms to embed the Individual Capital Assessment (ICA) calculations within their own risk management framework, which the FSA calls the "Use Test", they hope to raise the bar with respect to market and management practice and hence address the objective to maintain market confidence. Minimum prudential capital requirements for a firm are then set by the FSA (called Individual Capital Guidance or ICG which is private between the firm and the FSA) after reviewing a firm’s ICA and any other qualitative and quantitative information available.

The ICAS methodology may sound familiar to that employed by the rating agencies, as both are based on a risk-based framework. However, there are some significant differences between the two:

- ratings do not have a fixed capital number attached to them, although solvency is a significant part of the assessment;

- comparable insurance ratings exist across jurisdictions;

- ratings are publicly available for the benefit of the market (ICG is currently private); and

- ratings try to be as up-to-date as possible (although firms are also required to resubmit if there is a material change to their ICA).

Despite these differences, the approach to policyholder security by the rating agencies and the regulator/firms is now very similar. For the first time firms have to calculate their own risk-based capital calculations with an explicitly defined risk measure, time horizon and confidence level.

Hence, for firms there is a major change in the way their prudential capital is calculated. However, potentially more importantly, the Use Test requirement may change the way firms manage their business. By trying to ensure that capital calculations are embedded within the firm, the Use Test will help bring a relevant strategic tool into the Boardroom. For example, given the constraint of a set amount of capital, the strategy of insurers is to try and maximise future profits by dictating:

- new business in particular classes of business (underwriting/credit risk);

- management of existing business (reserve/credit risk);

- an appropriate investment policy (market/liquidity/credit risk); and

- an approach to managing frictional costs (operational risk);

within the confines of policyholder security and a security loading. The ICA calculation needs to incorporate all of these elements of a firm’s strategy and so in future could also be used to assist in the setting of strategy itself. To date, the most obvious example of this is via the firm’s business plans, which underpins the ICA calculation. However, in future it could take a more prominent role in the strategic and tactical decision-making processes of firms.

The above model looks at maximising profits given a set amount of capital. However, as discussed earlier, the ICA calculation is not usually equivalent to the amount of capital held by the firm. The FSA has to review the firm’s ICA and may provide ICG. In addition, the firm will also try to pitch the actual level of capital in order to attain a particular rating from the rating agencies based on their perception of policyholder’s appetite for security.

The FSA has said that they will try to be transparent in relation to the reasons for any differences between ICA and ICG. This will hopefully allow firms to incorporate any differences into future ICA calculations and in doing so make them more representative of prudential capital requirements and hence more useful as a strategic tool for the firm. Rating agencies will inevitably use the ICAS process within their rating assessments. As similar qualitative and quantitative information is utilised within both the rating and the prudential capital setting process there should be a closer crossover between ratings and capital requirements. Indeed the FSA would like to see firms make the link between ICG and actual capital held in line with the Use Test. If all qualitative information is taken into account within the ICG then higher ratings could simply be a function of additional capital. The critical question is will rating agencies be as transparent as the regulator in relation to differences between their rating and a firm’s ICG?

Some differences could simply be due to higher financial security ratings requiring more capital. However, as the process is very judgmental the rating agencies may just have a different point of view, particularly as they strive for consistency in their rating assessments worldwide. If rating agencies explain why more or less capital is required for a particular rating due to jurisdictional differences this would be valuable to firms in the course of setting future strategy.

For policyholders, the ICAS regime will try and ensure, through the setting of ICG, that firms have similar prudential capital security. However, policyholder’s varying appetite for capital security will mean that firms will continue to have different levels of capital security, as measured by the rating agencies, with the regulator trying to ensure that an appropriate minimum level of capital security is maintained by the market.

So the winds of regulatory change continue to sweep through the UK. In order to stay competitive in this changing regulatory landscape re/insurers need to be aware and embrace change. At Deloitte, our approach to ICA development is aligned with the Use Test in assisting our clients to gain some of the considerable benefits that the ICAS process can bring rather than being yet another regulatory cost. A key component of this is striking the right balance between shareholder profits and policyholder security/fairness. Management who recognise and utilise these benefits ahead of the market will undoubtedly be at an advantage. With the introduction of ICAS ahead of European and other worldwide capital initiatives, this should also place UK insurers and reinsurers in good stead to take advantage of the global re/insurance marketplace.

Article by Roger Jackson

Are you treating customers fairly yet?

Treating Customers Fairly used to be a matter of business and common sense – now it’s a regulatory requirement. The FSA’s reports suggest firms are making broadly satisfactory progress but Deloitte’s own industry healthchecks reveal some oversights and omissions. The challenge now is for firms to recognise and buy into the business benefits of the TCF agenda and inject some urgency into the process of implementing TCF measures – or face the consequences.

Many firms recognise the commercial importance of Treating Customers Fairly (TCF), and the publication of two key papers by the FSA in July 2005 has helped to reinforce the importance of firms understanding their obligations. The consumer research paper "Treating customers fairly: The consumer’s view" published by FSA in July 2005 attempts to define fairness in the eyes of the consumer through structured group discussions with consumer representatives. "Treating customers fairly – building on progress", also published in July 2005, sets out issues that should be considered when assessing how fairly the business treats its customers and provides a detailed update from the FSA since the publication of their last progress report in July 2004.

Key publications and dates

6 July 2005 Treating customers fairly: The consumer’s view

6 July 2005 Treating customers fairly – building on progress

6 July 2004 Treating customers fairly – progress and next steps

27 June 2001 Treating customers fairly after the point of sale

TCF is not a new concept. TCF was initially defined in Principle 6 of the Principles for Business (a firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly).

This Principle applies to all companies regulated by the FSA and the July 2005 TCF papers aim to assist financial service companies implement this Principle. TCF is principle based regulation, providing companies with flexibility in how they meet the requirements of TCF. It was felt that applying more prescriptive regulation would not provide companies with enough flexibility or indeed enhance consumer protection. If such an approach was taken companies may be more likely to follow a tick box approach to regulation rather than ensuring compliant practices that add value to their relationships with customers. To help guide companies in applying this principle, the FSA produced examples of good and bad practice that are presented in "cluster reports". Each cluster refers to a company’s activities in the following areas:

- product design;

- the interfaces between providers and distributors;

- staff remuneration;

- management information;

- complaints management; and

- managing strategic change (which focuses on depolarisation). The FSA have indicated that in the future, these clusters will expand to new areas.

For each cluster, the FSA has provided, in the "Building on progress" paper, examples of what should be considered when undertaking a review of compliance with the TCF principle. This paper applies to all financial service companies but does also list questions that are specific to general insurers. Some of the examples provided are as follows:

Product design and information

Are policy conditions unnecessarily complex and hence difficult for customers to understand?

Sales and advice

Is it clear to consumers what information they are being asked to provide in obtaining cover and what the consequences are of failure to provide comprehensive and accurate information?

Producer/distributor interfaces

Do firms have appropriate controls in place from a TCF perspective where product design is delegated to an underwriter?

Claims handling

Do firms rely on small print to avoid paying out even though it is unconnected with the event that gave rise to the claim?

Linked sales

How do firms manage their sales processes to protect against inappropriate sales of insurance that is bundled with other products?

Insurance intermediaries, regulated by the FSA since 14 January 2005, will also be concerned with implementing TCF. Changes in personal insurance distribution patterns means that TCF will be of relevance to traditional and non traditional insurance brokers, insurers themselves, affinity providers, banks and building societies.

Trade bodies, such as the Association of British Insurers (ABI), have been actively engaged and continue to provide helpful discussion forums and additional information for their members as well as help members put into practice the regulators guidance.

Where should firms be now?

As part of the July 2005 reports, the FSA provided an indication of how they felt the industry had progressed over the previous twelve months. These views were based on surveys of approximately 60 firms in Autumn 2004 and again in Spring 2005.

Although different samples of firms were surveyed, the results show a definite shift from the awareness phase through to the strategy and planning and implementation phases. In the main, these results support Deloitte experiences and the changes in types of queries from clients over the last year. However general insurance intermediaries, and particularly secondary intermediaries, who did not incorporate a TCF element to their Insurance Conduct of Business (ICOB) implementation project are lagging behind many companies who were regulated by the FSA prior to 14 January 2005.

According to the FSA surveys, an average firm is currently still in the strategy and planning phase, however more firms than before consider themselves to be entering the implementation phase than before. None of the firms surveyed considered themselves to be in the embedding phase, which is defined as the process of conducting a reinforcement exercise through the evaluation of, and modification to, existing TCF practices. It is unlikely that firms will be this well advanced for at least another twelve months.

The FSA’s approach is to use TCF work conducted with firms over the last twelve months to build expectations and inform of best practice as part of the supervisory process. TCF will become a core part of the Arrow risk assessment later this year.

Deloitte findings of TCF in practice

Deloitte has carried out a number of "healthchecks" to assess how successfully companies have implemented the ICOB rules and to identify gaps that still remain for compliance with the TCF principle. We have also carried out a mystery shopping exercise around the sale of home and motor insurance from a cross section of retail banks, insurance companies who sell direct and insurance intermediaries. Some of our findings are listed below:

- most companies had not linked their ICOB implementation projects with a TCF programme. Had they done so, duplication of effort could have been significantly avoided;

- middle management in some financial groups felt that ensuring compliance with ICOB requirements would automatically ensure the fair treatment of customers. They failed to see that the ICOB sourcebook contains only a relatively narrow set of rules and as such issues around product design, pricing structures, commission levels and other matters were being overlooked;

- focus on customers in companies’ strategies was not in all instances evident;

- meeting minutes lacked evidence of Executive Board attention to TCF;

- procedures for designing, logging, approving and tracking financial promotions were not consistently understood and applied across different areas of the business;

- the end product design was not always agreed by product management, actuarial, underwriting, compliance and the re-insurer before customer facing literature was being approved;

- it was often difficult to determine whether or not advice was being given during a telesales call. Despite executive decisions to go down the non-advised sales route, sales staff in some instances confirmed that they personally recommended the product being sold;

- many sales scripts did not require the company representative to get customers’ explicit consent to receiving only limited information about the product prior to the customer being asked for bank details. Whilst some companies debate when conclusion of a contract is, provision of bank details is likely to be viewed by the customer as his acceptance of the insurer’s or insurance intermediary’s quotation;

- the total cost of an insurance policy was not always made clear. For example, where a customer was initially provided with a single premium annual quote and subsequently provided with a monthly premium quote, the sales agent or website did not make clear that there was interest charged on the latter and as a result the monthly premium annual quote would be greater than the single premium annual quote initially provided;

- there was a risk that in some cases, customers would not receive product disclosure information because it was assumed that it was the ‘other company’s’ responsibility to issue. Neither new business process maps nor documented agreements were in place detailing insurers’ and intermediaries’ responsibilities in selling and administering a contract of insurance;

- sales staff were still being rewarded based on sales volume without proper consideration of sales quality;

- insurers were outsourcing aspects of claims handling to third parties but not adequately monitoring whether service level agreements were being adhered to. In particular, some were not picking up complaints made to third party suppliers regarding a claim being dealt with on behalf of that insurer;

- not all customer-facing staff were able to recognise a complaint and know the appropriate procedures to follow;

- most staff had received training on the implementation of the new FSA regulation around conduct of insurance business but less understood TCF as an FSA initiative and could not easily explain how it affected their day to day responsibilities;

- in most companies, compliance resource was an issue. It is extremely difficult for one or two people to keep up to date with all the relevant FSA publications, communicate these to the business, provide compliance expertise on a number of strategic change initiatives and business projects and monitor compliance to ensure FSA requirements are met and customers are treated fairly;

- in a few cases, insurance intermediaries were unable to provide a management information pack that was submitted to the board reporting on TCF matters; and

- specifically in the PPI market, whilst senior management were talking about TCF, certain generally accepted industry practices remained unchallenged.

The consumer angle

The consumer research paper published in July 2005 did not provide a final definition of fairness nor was it intended to. One of the main conclusions, unsurprisingly, is that consumers express different views on fairness depending on their financial sophistication, more than any other factor such as age or life stage.

The paper distinguishes between three different consumer types:

- dependent – lack confidence and knowledge in the industry and so are dependent on advice from other sources. Dependents are also the most vulnerable group;

- mass market – more confident but perhaps most cynical; and

- expert – the most knowledgeable and know what to expect.

The expert group seem a long way from the dependent group described in the paper; the dependents seem to have great misunderstanding and mistrust of the financial services market. Although not a finding in the research paper, the gulf of understanding between the dependents and experts reinforces the view that for TCF to be successful, it must be supported by programmes to increase the dependent group’s understanding of the financial services market.

The conclusions drawn on fairness by the consumer research take the form of six principles that financial services firms should adhere to:

- give the customer what they have paid for;

- do not take advantage of the customer;

- offer the customer the best product you can;

- do your best to resolve mistakes as quickly as possible;

- show flexibility, empathy and consideration in dealing with customers; and

- exhibit clarity in customer dealings.

All of these principles represent good common sense, and in fact to some extent are covered by existing FSA rules. For example the final principle should hopefully be covered by the existing FSA rules that require a firm to provide communications that are clear, fair and not misleading. It is unlikely that firms aim to treat customers any differently than these principles dictate; the real TCF test lies in interpretation and the customer experience.

Some specific issues arising from the FSA papers

In the July 2005 papers, the FSA have made it clear that they want firms to challenge ways of doing business that may be very familiar. This does not leave any room for complacency, and the FSA expects firms to test whether what happens ‘on the ground’ matches the fairness principles identified by the firm.

In the past, the FSA have made it clear that the responsibility for TCF falls with the senior management of firms, and that they must make a proportionate response that reflects the firms own culture and strategy. The responsibility for principle based regulation rests firmly with firms themselves, and the FSA stated that they wanted to see "intelligent, thoughtful and effective implementation by firms." For the first time in the most recent July 2005 paper the FSA state that failure to treat customer fairly may lead to enforcement action, resulting in a public censure or a penalty. Firms that have not taken any action at all on TCF to date, and where there is a significant risk to consumers may therefore face penalty, which is a much stronger message than has been talked of previously.

Some TCF results and benefits

The most useful information to be taken from the recent FSA papers lies in the examples of good and bad practice, and further good ideas are to be found in the more detailed information presented in the cluster reports. Examples of good practice include:

- product developers providing detailed training and literature to intermediaries on general technical issues as well as product specific issues;

- a product developer terminating relationships that might damage the provider’s brand, despite potentially losing large volumes of business;

- monitoring the quality of calls and taking this into account in the remuneration of customer service staff;

- TCF being included in quarterly reports to senior management from project directors engaged on major change programmes;

- creating an environment where complaints are seen as valuable feedback to help improve business performance;

- calling a complainant after receiving a complaint to check nature of complaint and gather more data; and

- business decisions explicitly taken in the context of the impact on each of a company’s important stakeholders: shareholders, customers and employees; giving equal weighting to shareholders and customers.

Next steps

Firms well advanced in the implementation of their TCF plans will be comforted with the picture that the latest FSA information paints, that they are on track with overall TCF delivery. For any firms that have not yet tackled TCF, or have only considered the governance of their TCF work the message is clear: Arrow visits and the threat of enforcement loom large.

Next steps:

1. Ensure TCF is on the Executive Board meeting’s agenda.

2. Review the FSA’s publications, speeches and feedback on TCF.

3. Define what TCF is for your business. For example understanding your customers, their needs and requirements, their views on your product and service offerings and their complaints with the business. Developing products, processes and services that respond to customers’ requirements and ensure they are treated fairly.

4. Conduct a gap analysis of your company’s arrangements for complying with TCF looking at: the company’s strategy, product design and approval procedures (including pricing), financial promotions, sales operations (including remuneration structures), claims and complaints handling, training and management information.

5. Implement your TCF programme by linking it with strategic change programmes and other business projects.

6. Review the implementation of TCF on an on-going basis to ensure it is properly embedded in the company’s culture and day to day operations.

7. Carry out any necessary "day two" work.

Arrow finds new targets

The first wave of Arrow visits to insurance intermediaries has taken place and many more intermediaries can expect a visit soon. These first reviews have revealed a number of interesting themes and the FSA too is learning about the process. Mark McIlquham and Colin Rawlings suggest that intermediaries down the line can look forward to higher expectations and rising standards as the FSA develops its view of best practice.

Intermediaries are well within the first year of FSA regulation, and many businesses will have undergone significant change improving their control environment and ensuring compliance with the FSA’s detailed requirements. The industry is now coming to terms with the full impact and consequences of applying the FSA Handbook (especially after the clarifications regarding the treatment of client money that were contained in "Dear CEO" letters). Many intermediaries will be now turning their attentions to their first Arrow visit, whilst a minority will be out the other side and attempting to deal with the challenges of their risk mitigation plans.

Overview of the Arrow process

The length of the FSA’s visit will be proportionate to the size and complexity of a business; after all, it is a risk based visit. Those smaller firms that the FSA decides to visit may only be visited for a day or two; larger, complex ones up to a week. The FSA will now be starting to build up a picture about the industry. As well as the application process, they will also have received the first Retail Mediation Activities Return (RMAR) submission from firms, and in addition, replies to the Client Money ‘Dear CEO’ letter. The FSA therefore now has information for it to subscribe firms with a risk profile. In addition we must not forget that the FSA is learning about the complex market in which general insurance is sold. They will be developing themes of ‘problem areas’ from their visits and establishing an overall ‘feel’ for ‘best practice’ by applying the best individual traits of each firm to create higher and higher overall industry standards.

Prior to their visit they will supply firms with a list of any information that they require to be prepared or made available for them in advance of their visit (e.g. minutes of board and committee meetings, internal audit reports and results of compliance

monitoring), and a list of the people from within the business they wish to interview. They will invariably start with the Chief Executive who is likely to have assumed the "Apportionment and Oversight" function, and will usually meet each of the approved persons (including non-executive directors (NEDs), compliance, internal audit and any other person they believe may be exerting significant influence over the running of the business. The FSA will be looking to understand from each of the approved persons:

- what their key responsibilities are and how they are apportioned with their other senior colleagues;

- how they control the area they are responsible for;

- what information that person receives from subordinates and also what they prepare (for the board and Chief Executive);

- what they see as the key risks within the business (and their specific area of responsibility) and how these risks are mitigated and controlled;

- whether they are aware of any significant rule breaches that have been uncovered during testing or any significant areas of ‘non-compliance’;

- an understanding of how the firm ensures that it treats customers fairly (TCF);

- how appointed representatives and introducers acting on the firm’s behalf are properly controlled? And

- how the firm is complying with the FSA’s client asset rules. From the information provided, the responses provided in the meetings, and their experience across the industry, the FSA will then work out which areas they wish to drill down into (this will already be prescribed if they are conducting a ‘themed’ visit).

Themes arising

There are now a number of recurring themes arising from these visits. Some will be similar to those arising in other newly regulated sectors (for example following N2); others are more bespoke to the general insurance intermediary sector.

Client assets

The FSA will be looking to validate the responses the firm provided in response to the Dear CEO letters, and in addition verify that where firms have promised to rectify procedures around client money as a consequence of this letter, firms have done what they said would be done. Many firms have struggled with the FSA’s requirement that the ‘client money resource’ and the ‘client money requirement’ are compared (and any gap plugged) within 24 hours of the month end close.

Other ‘common problems’ include the controls and procedures to ensure that sufficient additional client money is held to provide protection where client money is in the hands of its appointed representatives; and/or controls and procedures to ensure that sufficient additional client money is maintained where the original money has moved up the chain to another broker (and not yet reached the insurer) and the originating broker has not discharged his fiduciary responsibility for this client money. The FSA has identified this as a key risk and expects firms to be strictly adhering to these rules.

Corporate governance

A firm’s corporate governance framework underpins the whole structure that ensures regulatory compliance. The FSA expect firms to have a structure which is proportionate to its scale and complexity, and where a smaller firm has a less independent and less robust or non-typical structure, it must be able to defend to the FSA how and why this is appropriate, and how the board is receiving sufficient independent challenge, and affording sufficient protection to customers (especially retail). The FSA is not expecting every small organisation to have an internal audit department and risk committee, but will expect a degree of independent challenge that is commensurate with the scale and complexity of the organisation.

Challenge is likely to include the following:

- is the board appropriately structured, with experience covering all the major areas within the business and sufficient robust independent challenge from NEDs? This will be a challenge to all but the largest of intermediaries. These will be expected more in the ‘retail’ environment, or where there is not obvious choice at the point of sale (for example where the insurance is being sold in conjunction with another product and there is not an obvious alternative);

- does the board (and the approved persons) genuinely run the company and are the right people being ‘approved’ by the FSA? This area can be particularly challenging where the regulated business is a subsidiary of an overseas parent, who quite rightly will want some degree of control over its regulated investment in the UK. This also equally applies where the "owner manager" of a small broker does not formally have the apportionment and oversight function, but in reality still runs the business. The FSA require that they regulate those persons actually running a business;

- how can the internal audit department be independent if it reports to the CEO; and

- is an independent audit committee required?

Many firms will have decided that these functions are unnecessary for their business; this challenge becomes more difficult when they have been adopted within similar sized entities the FSA has already visited!

Robustness of monitoring and TCF

Although insurance intermediaries are only required to sell the customer a ‘suitable’ product, they still need to ensure that they have the appropriate level of information about that customer in order to assess this suitability. This will enable the intermediary to prepare a relevant and robust ‘statement of demands and needs’. These are likely be almost standardised for standard low margin retail business, and more detailed and bespoke for more specialist lines.

Files at intermediaries have been notoriously hard to follow (and find in many cases!) and these provide the easiest way of explaining why a certain recommendation was made after the event. The FSA is now expecting file indexes or standard documents, evidence of review and challenge at the time and this combined with a robust auditing or monitoring programme.

Many intermediaries revised their procedures and developed training for their staff in time for January this year. Nevertheless, it may be now many months since employees had their training, firms need to ensure that training programmes continue to evolve and standards are maintained. Some firms do not yet have a robust compliance monitoring plan that is risk based and designed to identify the offending brokers and staff. The controls around TCF only work if they are appropriately monitored, and even the best firms can get much better in this area by properly training their reviewers and developing a review function that is highly competent, but perhaps even more importantly independent, and making sure that samples and coverage of the business are sufficient, and that the process identifies the problem areas.

The bar will continue to rise

Most firms will be presented with challenge and areas for improvement from their visit. The FSA is itself seeking to understand how the handbook applies fully to an intermediary. As they see a good idea in one intermediary, they may adopt this as "best practice" and take it with them as a point for improvement when they visit the next intermediary. This will mean that standards within all intermediaries (and thereby the industry at large) will continue to rise.

Article by Mark McIlquham and Colin Rawlings