There are substantial tax savings available and, for some professionals, opportunities for income splitting. Budget 2016, however, introduced special anti-avoidance rules to prevent professionals from undermining the small business deduction rules, and these should be factored into professional corporation structures that involve partnerships. The corporate rules vary by province and territory. The federal tax rules, however, apply across the board.

A professional corporation (PC) allows professionals — such as, doctors, dentists, lawyers, and accountants — to provide their services to clients through a corporate entity, rather than personally. The corporate entity must be created under the auspices of provincial or territorial corporate statutes, and comply with rules determined by provincial regulatory bodies. The rules typically control the structure and operation of such entities to ensure that they do not violate, or circumvent, professional codes of conduct and practice.

MEANING OF PROFESSIONAL

Roscoe Pound defined a professional as a person "pursuing a learned art as a common calling in the spirit of public service — no less a public service because it may incidentally be a means of livelihood".1

Professions are generally regulated by independent bodies, determine their own rules of conduct and behavior, and typically protect themselves with monopolistic barriers. Daniel Duman identified the English bar as "the classic English profession as measured by nearly all the criteria usually associated with professionalism: autonomy from external interference, monopoly over practice, the possession of esoteric knowledge and skills, corporate unity and a position of dominance over a clientele dependent upon professional advice".2

For tax purposes, the definition of a "professional" is much broader than any of the traditional senior professions (lawyers, doctors, accountants, engineers, architects, etc.). A profession includes almost any occupation, other than individuals who engage in a personal services business3 as an "incorporated employee".4 Thus, with the limited exception for incorporated employees who earn personal service business income, almost any individual can form a professional corporation for tax purposes, and derive the appropriate tax benefits.

RATIONALE

The PC rules level the playing field for professionals so that they can operate in the same way as other individuals. However, there is one significant difference between professionals and nonprofessionals: Shareholders of PCs cannot limit their liability for negligence or malpractice, and they remain jointly and severally liable for all professional liability claims against them. This makes the choice of form of practice an important decision. Large law and accounting partnerships are typically better off practicing as limited liability partnerships (LLPs) in order to limit the personal malpractice exposure of their partners. On the other hand, sole proprietors, and small partnerships may be better off practicing as PCs for the tax advantages.

FUNDAMENTAL BUSINESS CONCEPTS

The fundamental business model of a professional corporation (PC) is that the corporate entity provides its services through an employee, who may also be its principal shareholder. The principal business imperative of a professional service corporation is that the entity must provide the services to, and contract with, the client or third party, even though it is the professional who personally delivers the service. Thus, the professional is the agent of the corporation. The corporation cannot be the agent of the professional.

Hence, a professional corporation should conduct itself like any other business corporation. This means that it is the PC that should:

- Enter into all contracts, including employment contracts;

- Enter into leases and contracts to acquire services;

- Operate its bank accounts;

- Promote itself in advertising; and

- Prepare financial statements.

In essence, the PC must deliver the services.

ENABLING STATUTES

Professionals can incorporate in all Canadian common law provinces under their respective corporate statutes. Although the various enabling statutes are similar, it is imperative that one consult the relevant applicable statute in the province of residence. In Ontario, for example, the Business Corporations Act, RSO 1990, c. B-16 (OBCA) is the governing statute for PCs.

Section 3.1 OBCA provides that:

"Where the practice of a profession is governed by an Act, a professional corporation may practise the profession if,

- that Act expressly permits the practice of the profession by a corporation and subject to the provisions of that Act; or

- the profession is governed by an Act named in Schedule 1 of the Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991, one of the following Acts or a prescribed Act:

- Certified General Accountants Act, 2010.

- Chartered Accountants Act, 2010.

- Law Society Act.

- Social Work and Social Service Work Act, 1998.

- Veterinarians Act. 2000, c. 42."

All of the common law provinces now allow lawyers to practice their profession through PCs. Subsection 3.2(2) OBCA sets out the structural and organizational conditions for creating PCs, as follows:

"Despite any other provision of this Act but subject to subsection (6), a professional corporation shall satisfy all of the following conditions:

- All of the issued and outstanding shares of the corporation shall be legally and beneficially owned, directly or indirectly, by one or more members of the same profession.

- All officers and directors of the corporation shall be shareholders of the corporation.

- The name of the corporation shall include the words "Professional Corporation" or "société professionnelle" and shall comply with the rules respecting the names of professional corporations set out in the regulations and with the rules respecting names set out in the regulations or by-laws made under the Act governing the profession.

- The corporation shall not have a number name.

- The articles of incorporation of a professional corporation shall provide that the corporation may not carry on a business other than the practice of the profession but this paragraph shall not be construed to prevent the corporation from carrying on activities related to or ancillary to the practice of the profession, including the investment of surplus funds earned by the corporation."

With the exception of physicians and dentists, where special rules apply5, subsection 3.2(2)(1) effectively precludes most other professions from splitting their professional income with family members who are not also members of the same profession. Thus, the rule prevents most lawyers from taking advantage of the income splitting tax benefits that are available to other businesses conducted through private corporations.

VOID VOTING AGREEMENTS

Voting agreements that vest powers or proxies in non-members of the profession are void if they remove powers from the shareholder, as are unanimous shareholders' agreements if all of the shareholders are not members of the PC (subs. 3.2(4) and (5) OBCA).

CONTINUED EXISTENCE OF CORPORATION

Subsection 3.3(1) OBCA provides for the continued existence of a PC despite:

- the death of a shareholder;

- the divorce of a shareholder;

- the bankruptcy or insolvency of the corporation;

- the suspension of the corporation's certificate of authorization or other authorizing document; or

- the occurrence of such other event or the existence of such other circumstance as may be prescribed.

UNLIMITED LIABILITY

A professional practicing his or her profession through a PC cannot limit his or her liability.6 Thus, the liability of a professional is not affected by the fact that the member is practicing his or her profession through a PC.7 The member is jointly and severally liable with his PC for all professional liability claims in respect of errors and omissions made during the tenure of his shareholding in the corporation.8

LIMITED LIABILITY PARTNERSHIPS

The liability of a shareholder of a PC that is a partner in a partnership is not affected by the existence of the PC structure. Thus, where a PC is a partner in a partnership, or limited liability partnership, the shareholders of the PC continue to have the same liability in respect of the partnership, or limited liability partnership, as they would have if they were directly the partners.9

REGULATORY RESTRICTIONS

A PC cannot carry on any business other than the practice of the profession of its shareholders. All of the shareholders of the PC must be members of the same profession: lawyers in the case of law firms, accountants in the case of accounting firms, etc. There can be no multi-disciplinary practices in a PC. A PC may, however, carry on any ancillary activities and can invest its surplus funds, including any cash saved from its deferred tax.

Professional regulators also stipulate various requirements and procedures to follow for PCs. For example, the Law Society of Upper Canada provides as follows:

"ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION MUST INCLUDE a clause in article 5 restricting the business of the professional corporation in accordance with section 3.2(2) 5 of the Business Corporations Act and section 61.0.1(5) of the Law Society Act. The following language appears to satisfy the requirements in the Business Corporations Act and the Law Society Act:

The corporation may not carry on a business other than the practice of law, but this paragraph shall not be construed to prevent the corporation from carrying on activities related to or ancillary to the practice of law, including the investment of surplus funds earned by the corporation.

ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION MUST INCLUDE a clause in article 8 restricting the issuance of the shares of the professional corporation. Refer to Section 3.2(2) 1 of the Business Corporations Act and section 61.0.1(4) of the Law Society Act. The Law Society has found the following share restriction language acceptable:

All of the issued and outstanding shares of the Professional Corporation shall be legally and beneficially owned, directly or indirectly, by one or more persons who are licensed to practise law in Ontario (such person or persons being hereinafter individually and collectively referred to as a "shareholder"), but this paragraph shall not be construed to prevent such shares from being transferred to, or otherwise owned by the estate trustee (or by the estate trustees, if more than one) of any deceased shareholder in accordance with the Law Society Act R.S.O. 1990, c L.8, or the Business Corporations Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. B.16, for the purposes of administering the shareholder's estate, but not for the practise of law."

ACCOUNTING FOR PCS

A PC carrying on a business is generally taxable on its income on an accrual basis. However, lawyers (but not paralegals), accountants, dentists, medical doctors, veterinarians, and chiropractors can elect to exclude any work in progress from their income at the end of the year.10 This benefit also extends to their PCs.11

THE SMALL BUSINESS DEDUCTION

As a general rule, CCPCs carrying on an active business in Canada can claim the small business deduction (SBD) or tax credit from tax otherwise payable. Subject to the tax rules and restrictions that apply generally, this privilege also extends to PCs.

There are many advantages (and some disadvantages) to incorporating a business. The essential advantage of a PC is that an individual can claim the federal SBD on business income up to $500,000, and defer tax on any income left in the corporation. For a CCPC, the SBD reduces the federal rate to 10.5%, and the combined federal provincial rate to about 15% (2016). The reduced rate allows a PC to defer tax on income that it retains in the corporation, which is a substantial tax advantage.

The small business deduction is phased out on a straight-line basis for a CCPC, and its associated corporations, that have between $10 million and $15 million of taxable capital employed in Canada.

The three basic requirements to claim the SBD are that the corporation must12:

- be a CCPC throughout the taxation year;

- earn active business income; and

- carry on its business in Canada.

Subsection 125(7) defines an active business to mean any business other than a specified investment business or a personal services business. The subsection defines a "personal services business" (PSB) as a business of providing services where the individual who performs the services on behalf of the corporation ("the incorporated employee") would reasonably be regarded as an employee of the person or partnership to whom the services were provided but for the existence if the corporation. Thus, in effect, a PSB exists where the relationship between the individual and the corporation would, in substance, be an employment relationship if the corporation was not placed between the individual and the client to whom he or she provides the services.13

The risk of being considered a PSB is greatest where the corporation has only a single client, and the individual providing the services is highly integrated into the client's operations. The underlying historical relationship between the parties is a relevant factor. The essential question is whether the individual is a de facto employee within the legal meaning of employment relationships.14 The level of control of the "employer" over the "worker" is an important, but not a determinative, factor. The question is one of fact and, as such, beyond the scope of CRA rulings.

In McCormick v. Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP,15 for example, the taxpayer was an equity partner in his law firm, and was forced to retire at age 65. The partnership agreement required equity partners to divest their ownership shares in the partnership at the end of the year in which they turned 65. The Supreme Court considered the degree of control and dependency to be significant factors in determining an employment relationship in the context of the British Columbia Human Rights Code.

The tax deductions of a PSB are limited to the salary and benefits paid to employees, and taxable income is taxed at a flat rate equal to the top personal tax rate.

SPECIFIED PARTNERSHIP INCOME

Paragraph 125(1)(a) of the Act adjusts the amount of "active business income" (ABI) of a partnership eligible for the SBD by restricting the amount to its "specified partnership income". Subsection 125(7) allocates the $500,000 SBD limit to partners in proportion to their percentage partnership interest. For example, a 25 percent partner carrying on business through a PC would be limited to a maximum ABI amount of $125,000 in a year. Thus, in effect, a partnership of several PCs is entitled to only one $500,000 threshold limit. These rules are subject to special anti-avoidance rules (see below).

INCOME SPLITTING

Members of a professional PC may be able to split income with non-professionals, but only if the relevant provincial legislation permits the admission of the non-professional. Law societies typically do not allow non-lawyers to be members of a legal PC. Nevertheless, family members can the employees of the PC and receive reasonable compensation for services. In such cases, CPP and EI payments may apply. There are special rules in respect of medical practitioners.

TAX DEFERRAL

For most professionals, the most compelling reason for incorporating is to benefit from corporate tax advantages. The principal advantage from a PC is tax deferral. The difference between the tax payable by incorporated and unincorporated professional practices is significant. Individuals pay tax on their business income at progressive marginal tax rates. For example, in 2016, the top combined federal/ provincial marginal tax rate on ordinary income is about 53.53 per cent in Ontario for income that exceeds $220,000, (47.70 per cent in B.C.; 48 per cent in Alberta for income that exceeds $300,000). In contrast, the combined federal and provincial corporate rate of tax is approximately 15 per cent on the first $500,000 of professional business income, and 26.5 per cent on income above $500,000. The spread between personal and corporate tax rates allows professionals to defer tax if they leave their income in the corporation. Since business partners must share the $500,000 limit between themselves, the full benefits of incorporation accrue only to sole practitioners and small partnerships.

The following table illustrates the 2016 tax differentials on $100,000 income (assuming personal income is taxed at 53.53 per cent (Ontario)) earned in a proprietorship versus income that an individual earns in a PC.

The above table shows that the tax payable on business income is nearly perfectly integrated where the corporation pays out its income as dividends to shareholders. The real advantage of tax deferral, however, is where the corporation accumulates its income, and does not pay it out immediately to its shareholders. In the above example, the tax on the dividends is payable only when the corporation pays the dividends. Until then, the tax thereon is deferred. The following table illustrates the power of compounding the tax deferred income over an extended period:

Tax deferral is a real and substantial tax saving, which can accumulate into very significant amounts, but only if the individual does not immediately require all of his or her earnings for personal use. The deferral stems from the ability of the shareholder to leave some of the after tax corporate earnings in the corporation. The magnitude of any deferral depends upon the reinvestment rate, and the length of time that the corporate entity accumulates its income. Thus, professionals can use tax deferral as a surrogate pension plan.

Since tax deferral is the key to planning with a PC, one should clearly understand the mathematics of the time value of money and discount rates in advising clients on corporate structures. Without tax deferral, there is no advantage to a PC. Indeed, there are distinct disadvantages in the form of higher costs in maintaining and operating a corporation.

REMUNERATION

Incorporation may also enhance remuneration flexibility, and allow the owner-manager to choose between receiving compensation as salary or dividends. The decision to pay salary or dividends out of a corporation must take into consideration the personal circumstances of the owner — manager. The following are some of the salient factors that the owner should take into account:

- Salaries are generally deductible by the corporation as an expense, and are taxable to the individual;

- Salaries are subject to payroll deductions for taxes and CPP;

- Dividends are paid with after-tax dollars by the corporation;

- There are no payroll deductions from dividends;

- Salary creates room for RRSP purposes; and

- Salary creates pensionable earnings for CPP purposes.

Thus, the ultimate decision should balance these considerations in arriving at the optimum salary versus dividend mix.

For example, professionals may wish to receive sufficient salary income to allow them to contribute to a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) and Canada Pension Plan (CPP). In other circumstances, an individual may prefer dividends if he has a cumulative net investment loss (CNIL) and wants to claim the capital gains exemption.

COSTS OF ADMINISTRATION

Administrative costs are a relevant factor in setting up professional corporations. One of the major advantages of a PC is the opportunity to defer taxes on business income left in the corporation for investment purposes. The costs of administration may, however, outweigh the tax advantages if the professional needs to extract all of the PC's business income in each year.

HOLDING COMPANIES

Depending upon the applicable provincial legislation, professionals may be able to use a holding company (Holdco) to own the shares of a PC, and siphon off professional earnings to the holding company through tax-free dividends. This will reduce shareholder risk in the PC, and allow the saved cash to accumulate in Holdco. To be sure, there is no real risk in leaving surplus funds to be reinvested in the PC itself if the professional shareholder is fully and adequately insured against negligence. A Holdco, however, adds greater certainty to the structure.

There are opportunities in some provinces to split income between family members, but such structures should take into account the attribution rules, and the special "kiddie tax" on certain income that minors can earn from such structures. The kiddie tax can neutralize any benefits from income splitting business income in corporations in which the parents participate actively. Professional regulators may also restrict the use of holding companies. For example, the Law Society of Upper Canada states:

"The ownership of shares in a holding company must be restricted to licensee(s). Shares in a holding company may not be owned by family members or non-licensees. In addition, the business of a holding company must be restricted to holding the shares of the professional corporation. Applicants who intend to use a holding company must submit the Articles of Incorporation for the holding company along with their Application for a Certificate of Authorization."

LIFETIME CAPITAL GAINS EXEMPTION

The shares of a PC that qualifies as "small business corporation" (SBC) may be eligible for the lifetime capital gains exemption when the shareholder disposes of his or her shares. In general terms, a SBC is a Canadian-controlled private corporation that uses all, or substantially all, of the fair market value of its assets in an active business in Canada. The exemption is worth $824,176 in 2016, and is indexed thereafter.

DISADVANTAGES OF INCORPORATION OF PC

There are also some disadvantages of incorporating and operating through a PC. For example:

- Expenses of incorporation;

- Annual maintenance of corporate entity;

- CRA payroll deductions and monthly remittances;

- HST registration and remittances; and

- Corporate accounting and tax returns.

ANTI-AVOIDANCE RULES

A Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC) can claim a small business deduction, which will reduce the federal corporate tax rate from 28 per cent to 10.5 per cent on the first $500,000 per year of qualifying active business income. The combined federal-provincial rate on a small business is about 15 per cent. The $500,000 annual limit must be shared among associated corporations, and where appropriate, members of a partnership that earns active business income.

A CCPC calculates its small business deduction for a year based upon:

- its active business income from sources other than a partnership, and

- its specified partnership income (SPI).

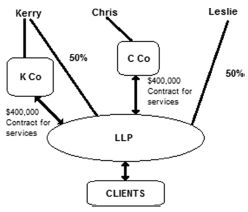

A partner's SPI is the lesser of the partner's share of the ABI of the partnership, and his or her pro rata share of the $500,000 business limit, which all of the partners must share in respect of the partnership's income. Thus, in general terms, the small business deduction that a CCPC that is a member of a partnership can claim in respect of its income from the partnership is limited to the lesser of the active business income that it receives as a member of the partnership (its "partnership ABI"), and its pro-rata share of a notional $500,000 business limit determined at the partnership level (its specified partnership income limit, or "SPI limit").The theory of the small business deduction rules intend to preclude multiplication of access to the deduction. However, some innovative partnership and corporate structures managed to multiply access to the small business deduction. For example, some partnerships structured their arrangements so that a shareholder of a CCPC would become a member of the partnership, which would then pay the CCPC as an independent contractor under a contract of services. Since the CCPC would not be a member of the partnership, it could claim the entire $500,000 business limit as a small business deduction on its ABI. The following is a simple example of such a structure.

In the above example, X Co., Y Co., and Z Co. could circumvent the overall limit and each claim up to $500,000 of the small business deduction. To prevent the above type of tax planning in multiplying the small business deduction, Budget 2016 extended the specified partnership income rules (SPI) to structures in which a CCPC provides (directly or indirectly) services or property to a partnership during a taxation year of the CCPC where, at any time during the year, the CCPC or a shareholder of the CCPC is a member of the partnership or does not deal at arm's length with a member of the partnership.

The rules deem the CCPC to be member of partnership and income as SPI, where:

- the CCPC provides service or property to partnership,

- the CCPC is not otherwise a member of

the partnership, and

- One shareholder of the CCPC holds a direct or indirect interest in partnership, or

- The CCPC does not deal at arm's length with the partnership, and

- the CCPC does not derive 90 per cent or more of its ABI from arm's length parties. Example

- Kerry and Chris are married.

- Kerry and Leslie each have a 50% interest in the limited liability partnership (LLP).

- Leslie deals at arm's length with Kerry and Chris.

- None of K Co, C Co or Chris are members of the LLP.

- LLP provides accounting services to the public.

- Kerry owns 100% of K Co and Chris owns 100% of C Co.

- LLP has $200,000 of net income to allocate to its members.

- K Co and C Co each earn $400,000 from providing accounting services to LLP.

The following consequences would apply under the new anti-avoidance rules in Budget 2016:

Leslie

- Leslie is taxable on $100,000 at personal income tax rates.

Kerry/K Co

- Kerry is taxable on $100,000 at personal income tax rates.

- K Co is deemed to be a partner of LLP because it does not deal at arm's length with Kerry, and provides services to LLP.

- The full $250,000 of Kerry's SPI limit is assigned by Kerry to K Co (i.e., 50% of the partnership's $500,000 business limit is what Kerry's SPI limit would be if Kerry were a corporation). (Alternatively, Kerry could have assigned all or a portion of his $250,000 SPI limit to C Co.)

- K Co pays $48,750 of federal tax on $400,000 (income eligible for the small business deduction ($250,000) multiplied by the small business tax rate (10.5%), plus income not eligible for the small business deduction ($150,000) multiplied by the general federal corporate tax rate (15%)).

- Chris /C Co

- C Co is deemed to be a partner of LLP because it does not deal at arm's length with Kerry, and provides services to LLP.

- C Co pays $60,000 of federal tax on $400,000 (income not eligible for the small business deduction ($400,000) multiplied by the general federal corporate tax rate (15%)).

CORPORATIONS

Tax planning similar to that described above could use a corporation (instead of a partnership) to multiply access to the small business deduction. Thus, similar anti-avoidance measures apply to corporations that seek to multiply the small business deduction where a CCPC earns its income by providing services to a private corporation in which the CCPC, one of its shareholders, or a person who does not deal at arm's length with the shareholder has a direct or indirect interest. In general terms, a CCPC's active business income will not be eligible for the small business deduction unless it earns all or substantially all of its ABI by providing services to arm's length persons, other than the private corporation.

TAX AVOIDANCE

The associated corporation rules in section 256 of the Income Tax Act intend to contain the $500,000 business limit, and the $15 million taxable capital limit to CCPCs. The rules attempt to balance between allowing family members to carry on businesses through separate CCPCs eligible for the small business deduction, but restrict arrangements that a single economic group may use to multiply the small business deduction.

Thus, there are a variety of technical rules that determine whether two or more corporations are associated with each other. For example, subsection 256(1) provides that two CCPCs will be associated with each other if the same person (or group of persons) controls them. Similarly, they will be associated with each other if they different related persons control them and one of related persons (or their CCPC) owns at least 25% of the shares of the other CCPC. However, a corporation that is wholly owned by an individual is generally not associated with a corporation that is wholly owned by the individual's spouse, sibling or another related individual.

There is a special rule, in subsection 256(2), under which two corporations that would not otherwise be associated will be treated as associated if each of the corporations is associated with the same third corporation.

Since the $15 million taxable capital limit is based on the capital of associated corporations, none of the corporations would be eligible to claim the small business deduction if the total taxable capital of the three corporations exceeds $15 million. However, subsection 256(2) provides an exception to this special rule: two corporations that would otherwise be associated with each other because they are associated with the same third corporation will not be treated as being associated with each other if:

- the third corporation is not a CCPC or,

- if it is a CCPC, it elects not to be associated with the other two corporations for the purpose of determining entitlement to the small business deduction.

The effect of this exception is that the third corporation cannot itself claim the small business deduction (if it is a CCPC), but the other two corporations may each claim a $500,000 small business deduction subject to their own taxable capital limit.

Some CCPCs multiplied their small business deduction are being challenged by the Government under a specific anti-avoidance rule, and under the general anti-avoidance rule. Others claimed the small business deduction on investment income.

Such challenges are time-consuming and costly. Hence, the Government introduced specific legislative measures to ensure that the appropriate tax consequences apply.

Budget 2016 amended the Income Tax Act to ensure that investment income derived from an associated corporation's active business will be ineligible for the small business deduction and be taxed at the general corporate income tax rate where the exception to the deemed associated corporation rule applies (i.e., an election not to be associated is made or the third corporation is not a CCPC).

In addition, where this exception applies (such that the two corporations are deemed not to be associated with each other), the third corporation will continue to be associated with each of the other corporations for the purpose of applying the $15 million taxable capital limit.

CONCLUSION

PCs and CCPCs allow professionals considerable flexibility in arranging their business affairs for maximum after-tax retention of earnings. The corporate and tax rules allow professionals and shareholder carrying on business substantial savings through tax deferral on active business income. Medical professionals also have opportunities for income splitting. However, the key prerequisite is that all professional corporations must comply with provincial corporate rules, the local rules of professional conduct, and, of course, federal tax rules in respect of professional services businesses, and in particular the anti-avoidance rules in respect of associated corporations.

This article was originally published in the December 2016 Canadian Current Tax

[Vern Krishna, CM, QC, FRSC is Professor of Common Law at the University of Ottawa, and Tax Counsel, Tax Chambers, LLP (Toronto). He is a member of the Order of Canada, Queen's Counsel, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and a Fellow of the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada. His practice encompasses tax litigation and dispute resolution, international tax, wealth management, and tax planning. He acts as counsel in income tax matters, representing corporate and individual clients in disputes with Canada Revenue Agency, and appears in all courts as tax counsel.]

Footnotes

1 Roscoe Pound, The Lawyer from Antiquity to Modern Times (St. Paul, Minn.: West Publishing Co., 1953), p. 5. Contrast this definition with an earlier one: " ... broadly characterized as non-manual, non-commercial occupations sharing some measure of institutional self-regulation and reliance on bookish skills or training ... ": W.R. Prest, The Rise of the Barristers - A Social History of the English Bar 1590-1640 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), p. 2.

2 Daniel Duman: The English and Colonial Bars in the Nineteenth Century (Beckenham, Kent: Croom Helm Ltd., 1983), Introduction.

3 Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp), para. 18(1)(p).

4 Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp), para. 125(7) "personal services business".

5 The Lieutenant Governor in Council may make regulations under subsection 3.2(6):

- "(a) exempting classes of health profession corporations, as defined in section 1 (1) of the Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991, from the application of subsections (1) and (5) and such other provisions of this Act [OBCA] and the regulations as may be specified and prescribing terms and conditions that apply with respect to the health profession corporations in lieu of the provisions from which they are exempted;

- (b) exempting classes of the shareholders of those health profession corporations from the application of subsections 3.4 (2), (4) and (6) and such other provisions of this Act and the regulations as may be specified and prescribing rules that apply with respect to the shareholders in lieu of the provisions from which they are exempted;

- (c) exempting directors and officers of those health profession corporations from the application of such provisions of this Act and the regulations as may be specified and prescribing rules that apply with respect to the directors and officers in lieu of the provisions from which they are exempted."

6 For example, subsection 3.4(3), Business Corporations Act, RSO 1990, c B.16.

7 For example, subsection 3.4(3) Business Corporations Act, RSO 1990, c B.16.

8 See, for example, subsection 3.4(4) Business Corporations Act, RSO 1990, c B.16.

9 See, for example, subsection 3.4(6) Business Corporations Act, RSO 1990, c B.16.

10 Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp), s. 34.

11 Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp), ss. 125(1).

12 Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp), ss. 125(1).

13 See, Dynamic Industries v. Canada, [2005] FCJ No 997, [2005] 3 CTC 225 (FCA).

14 See, Wiebe Door Services Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1986] FCJ No 1052, [1986] 2 CTC 200 (FCA); 671122 Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries Canada Inc., [2001] SCJ No 61, [2001] 4 CTC 139.

15 [2014] SCJ No 39, [2014] 2 S.C.R. 108.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.