The Federal Court of Canada recently released a decision on the infringement and validity of two designs registered under the Industrial Design Act. In Bodum USA Inc. et al v. Trudeau Corporation (1889) Inc., 2012 FC 1128 (Bodum), Boivin J. dismissed the plaintiffs' infringement action and allowed the defendant's counterclaim of invalidity, expunging the industrial designs from the register. Bodum provides new insights into the Canadian approaches to infringement and validity assessment, and a fresh opportunity to compare Canadian practices with those in other jurisdictions, such as the United States following the staggering jury verdict in Apple v. Samsung, No. CV-11-1846 (N.D. Cal 2012).

The two industrial designs in question in Bodum consisted of the visual features of double-walled drinking glasses. Section 2 of the Industrial Design Act defines a "design" as being the "features of shape, configuration, pattern, ornament and any combination of those features that, in a finished article, appeal to and are judged solely by the eye." Justice Boivin began his infringement analysis by reaffirming that industrial designs do not confer a monopoly over functional elements, and as such, the similarities in utilitarian function between two products are not to be considered by the court in an infringement analysis. Furthermore, Justice Boivin also stated that Bodum's registrations claim their respective designs in their entireties as opposed to in part. Therefore, to establish infringement in this case, "there must be something reasonably approaching identity."

With the aid of a single expert witness presented by the defendant, Justice Boivin undertook a detailed analysis of prior art designs and the respective shapes of the registered designs and the defendant's glasses.

The parties argued that different legal tests should apply when deciding the question of infringement. As a starting point, the Act provides that infringement occurs when the registered design or "a design not differing substantially therefrom" is applied to an article without permission (s.11[1][a]). The plaintiffs advocated for applying a three-pronged test whereby the designs that are subject to the comparison are not viewed side by side but separately so that imperfect recollection can guide the visual perception of the finished article. However, Justice Boivin agreed with the defendant and held that the allegedly infringing product must be analyzed on a side-by-side basis from the point of view of how the informed/aware consumer would see things. Justice Boivin found support in Rothbury International Inc v. Canada (Minister of Industry), 2004 FC 578 (Rothbury). Interestingly, Rothbury concerned an appeal of a decision to refuse registration and clarified how the test for originality is to be applied. Infringement was never in issue. This illustrates how closely the tests for infringement and originality (validity) are aligned in Canada.

In considering whether differences are substantial, Section 11(2) of the Industrial Design Act states that the extent to which the registered design differs from any previously published design may be taken into account. In applying this test to the glasses at issue, Justice Boivin found that the defendant's glasses did not have the features attributed to them by the plaintiffs and were, in fact, more similar to the prior art glasses — including one of Bodum's own prior designs — than they were to the registered designs. Bodum's prior design, its registered designs and Trudeau's glasses are reproduced from Bodum below:

Furthermore, Justice Boivin also rejected the plaintiffs' argument that the translucent double wall of the defendant's glasses made them similar to the registered designs. It appeared that Justice Boivin rejected the argument on the basis that these configurations were not particularly illustrated or described (see par. 61 and par. 89).

When conducting a validity analysis on the plaintiffs' designs, the court reiterated that to be registrable, an industrial design has to be substantially different from the relevant prior art and that a simple variation is not sufficient. The degree of originality required is higher than for copyright and involves at least a spark of inspiration in creating a new design or in hitting upon a new use for an old one. After comparing the prior art submitted into evidence and the Bodum registrations in question, Justice Boivin determined that, in each case, the respective Bodum design in question does not vary substantially:

"...the evidence nevertheless demonstrates that the field of glassware, like the fields of shirt collars and shoes, is a field that has existed for a long time. They are articles used daily and, therefore, the differences must be marked and substantial."

In Bodum, Justice Boivin has affirmed that the originality requirement for obtaining an industrial design registration is relatively onerous, particularly for products in common use. The burden of proof for infringement has also been raised: an infringement analysis must be conducted from the point of view of an informed consumer rather than through that of an expert or by using the doctrine of "imperfect recollection" looking for confusion as advocated in earlier cases. Bodum teaches that an "informed eye of the court" approach may involve instruction of the court by experts to present prior art and to conduct analysis of the registered and accused designs in a side-by-side manner to determine whether the designs are substantially the same. (See also Algonquin Mercantile Corp. v. Dart Industries Canada Ltd., [1984] 1 CPR [3d] 75.) The reasoning of Justice Boivin raises fundamental questions about infringement and validity, and a number of the findings do not appear to be self-evident. For example, in a crowded field analysis, does it not make sense to acknowledge that a number of small distinguishing features taken together may function effectively as a substantial difference? A Notice of Appeal has already been filed by the plaintiffs, so perhaps the Federal Court of Appeal will take the opportunity to readjust the height of the bar.

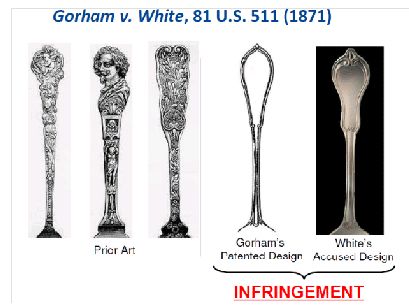

The Bodum infringement analysis is quite similar to the approach taken in the United States. The U.S. test was first adopted by the Supreme Court in the 1871 decision of Gorham v. White, 81 U.S. 511 (Gorham), where the required comparison was to be undertaken by an "ordinary observer," not an expert, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives. The patented design and accused design must be substantially the same. The comparison is done in light of the prior art, and a side-by-side comparison is undertaken.

In Gorham, the accused design and patented design had many differences, but the accused design was much more like the patented design than the prior art:

(Carani, C., Longwell, J., Industrial Designs Take Centre Stage: Apple v. Samsung, IPIC Webinar, Nov. 30, 2012.)

The U.S. test for validity may be contrasted to the Canadian test in part because U.S. design rights are patent rights, and U.S. law in this regard speaks of novelty and non-obviousness requirements. In practice, the results do not appear to be markedly different. Both reviews under U.S. and Canadian law take into account the prior art and involve a comparison to determine whether a substantially different design exists. The U.S. test speaks of reviewing obviousness in relation to the new design from the point of view of a person skilled in the art. This notional person may be akin to a design expert and attributed with a keener or more knowledgeable eye than the ordinary observer employed for an infringement analysis. In Bodum, the informed consumer appears to be the notional person employed for both infringement and originality tests.

In trial practice in the U.S., the analysis is ultimately conducted by members of the jury as instructed by the judge while in Canada, the judge alone is the trier of fact.

In Apple, numerous design patents and accused products were under review by the jury. Curiously, the jury refused to find infringement of Apple's tablet design where in a preliminary injunction ruling, Judge Koh opined that one of Samsung's accused tablets was "virtually indistinguishable" from the Apple design. The decision in Apple is not finally determined, and it will be interesting to see whether Apple can overturn the jury's verdict with respect to the tablet designs — and whether Samsung can overturn any of the many findings of infringement against its various communication devices and graphical user interfaces.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.