With effect from 1 February 2016, every court sentencing a health and safety conviction, must follow the Sentencing Council's Definitive "Guideline for Health and Safety Offences, Corporate Manslaughter and Food Safety and Hygiene Offences".

The Guideline requires offences to be categorised according to the degree of culpability and degree of harm risked, and for that categorisation to be applied to one of a number of tables which suggest a range and starting point for the financial penalty to be imposed. Annual turnover of a business will determine whether the table to use is for "micro", "small", "medium" or "large" organisations. The Guideline suggests that where an offending organisation's turnover "very greatly exceeds" the £50 million threshold which defines large organisations, it may be necessary to move outside the suggested range to achieve a proportionate sentence.

Fine Predictability and Banding Arguments

For businesses with turnover around or below £50 million, the Guideline has afforded a relatively high degree of predictability for fines on conviction with its tables and harm and culpability bands. That is helpful, even if the fines are now routinely higher than they were before the introduction of the Guideline. For the very large organisations ("VLOs"), while the starting point for a fine is the "large" organisation table, how has the Court approached the guideline which suggests moving outside the suggested range to achieve proportionate sentencing?

It has always been the case that it is relatively rare for health and safety prosecutions to be defended (and even more uncommon for a defence to succeed). The offences under the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 ("HSWA") in particular are very widely and subjectively drafted. Section 40 of the Act reverses the burden of proof in relation to many of the duties which the Act imposes and which, in turn, depend on an assessment of what was reasonably practicable in order to manage and minimise risk. That, coupled with the presumption that the required standard has not been met when there is an accident, does mean that these cases are difficult to defend.

With higher fines certain under the Guideline, most defendants of any size, prefer to benefit from the increasingly valuable uncapped early guilty plea discount of up to one third rather than gamble the certain loss of that discount against the uncertain success of a not guilty plea.

Harm and culpability

As a result of the banding, arguments in the health and safety cases prosecuted post Guideline have focused not on what was or wasn't reasonably practicable and whether the defendant has breached HSWA duties, but have received early guilty pleas (to achieve the one third early guilty plea credit) and focused on:

- Culpability - how far short of expected standards did the defendant fall, whether the breach was flagrant or minor what had been done to avoid the risk of an accident

- Harm - whether the accepted breach posed a high, medium or low likelihood of harm, how serious that harm might be, how many people were put at risk by it and whether the risk actually caused harm

There is a higher differential for the fines suggested between harm categories than between culpability categories. But when prosecution in fact follows a serious accident, there is perhaps less scope for successful argument regarding the harm category than there may be on the culpability category. The cases so far reflect less movement by the Court from the prosecution's position on harm category than culpability category.

The arguments regarding categories are leading to more "mini trials" of these issues (known as Newton hearings) and although this will increase the costs payable, this may be justified where a shift in category might reduce a fine by £2 million.

To illustrate the importance of the categories, for a large organisation:

| Starting point for fine | Category range suggested for fine | Impact of category change on fine starting point | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very High Culpability | |||

| Harm Category 1 | £4,000,000 | £2,600,000- £10,000,000 | Harm cat. increase = £2 million |

| Harm Category 2 | £2,000,000 | £1,000,000 - £5,250,000 | |

| High Culpability | |||

| Harm Category 1 | £2,400,000 | £1,500,000 - £6,000,000 | Culpability cat increase = £1.6 million |

| Harm Category 2 | £1,100,000 | £550,000 - £2,900,000 | Harm cat increase =

£1.3 million Culpability cat. Increase = £900k |

Given that the tables only suggest fines and ranges for businesses with turnover (or equivalent for public sector organisations) of up to "£50 million and over", one of the biggest early concerns post Guideline was whether the fine that the large organisation table suggested, would be ramped up to achieve the objective of proportionate sentencing for VLOs.

That is not, however, what has happened in practice.

So far, the approach adopted by the Court to sentencing VLOs has been that the Court will fit the offence into the large organisation table. While the size of the business seems to influence the penalty dropping into the upper end of the suggested fine bracket, mitigation has been given as the reason to justify not pushing the VLOs into a higher bracket or beyond the table altogether for sentencing, and aggravating features (not size of the company's turnover) as the reason in some cases for elevating a fine up a culpability bracket.

In the Sentencing Remarks of Judge Cole sitting in Aylesbury in April this year, on the conviction of a VLO (Travis Perkins), he noted the objective of ensuring that the fine is sufficiently large to bring the appropriate message home to the directors and shareholders and to punish them but said:

In that matter, he imposed a fine near the top end of the range (£3 million), before reducing the fine by one third to reflect the early guilty plea, which brought it down to £2 million.

In the Merlin Attractions ("Alton Towers") case by contrast, His Honour Judge Michael Chambers QC, while putting the case initially within the high culpability, harm category 1 bracket (for which the suggested fine range is £1,500,000 to £6,000,000 on the large business table), and saying a "proportionate sentence can be achieved within the offence range", then decided that the aggravating features of the case (not the financial size of the business) were sufficient to push this matter into the very high culpability bracket where a category 1 harm case has a recommended fine range of £2,600,000 to £10,000,000. He imposed a fine of £7,500,000, reduced by one third by reason of early guilty plea, to £5,000,000. Below, I look further at the specific mitigating and exacerbating features of these cases, which appear to have been pivotal in the sentencing decisions.

The interesting thing about these decisions is that the scope through mitigation and aggravating features for cases to move up and down the sentencing brackets is a risk that impacts any convicted business. It is not something that is only for consideration when the defendant happens to be a VLO.

Context of the Large Fines and Trends

Although 33 large organisations and VLOs have been convicted for health and safety and corporate manslaughter offences in the first eight months post introduction of the Guideline, it is not the case that the VLOs have always received the highest fine.

In no case has any Court yet deemed it necessary to go beyond the suggested fine range afforded to them by the large organisation sentencing table which extends to £10 million at the top end for non-corporate manslaughter health and safety offences.

Only 14 organisations have received fines at or over £1 million in this eight month period. Small organisations (turnover £2 million to £10 million) have received fines up to £1.2 millon, and medium organisations (turnover £10 million - £50 million) fines up to £1.5 millon.

The average fine for the 29 convicted VLOs has been under £1,070,000 (highest fine £5 millon). Pre Alton Towers and Network Rail sentences in September, the average health and safety fine for VLOs was just under £815,000 compared with the average of £640,000 for large organisations. Post Alton Towers and Network Rail the average fine for VLOs as illustrated below, now exceeds £1 million.

| Size | No. of prosecutions? | Sum of fine | Average fine | Maximum fine | Minimum fine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Large: Greatly exceeding £50 million | 29 | £30,966,000 | £1,067,793.10 | £5,000,000 | £100,000 |

| Large: £50 million and over | 4 | £2,560,000 | £640,000 | £1,600,000 | £60,000 |

| Medium: £10 million - £50 million | 27 | £7,866,500 | £291,351.85 | £1,500,000 | £6500 |

| Small: £2 million - £10 million | 15 | £2,307,500 | £153,833.33 | £1,200,000 | £3500 |

| Micro: Not more than £2 million | 8 | £659,400 | £82,425 | £550,000 | £0 |

| Exempt | 65 | £3,225,602 | £49,624.65 | £500,000 | £2 |

| Insolvent | 4 | £1,046,000 | £261,500 | £600,000 | £70,000 |

| Not applicable | 58 | £90,756 | £1564.76 | £16,000 | £0 |

| Not known | 10 | £856,487 | £85,648.70 | £500,000 | £4487 |

| Total | 220 | £49,578,245 | £225,355.66 | £5,000,000 | £0 |

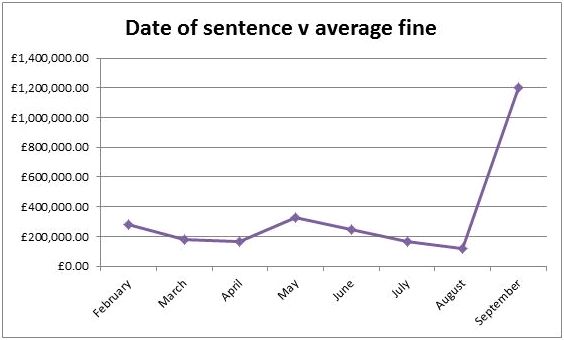

We had expected that the fines would generally increase with time as judicial confidence with the more punitive sentencing Guideline settled down. In fact, without the Alton Towers and Network Rail convictions which sharply push up the average fines for September up to £1.2 million, there is not yet a clear statistical pattern that demonstrates any such pattern.

Is September a step-change?

14 fines at or over £1 million out of 222 convictions are indicative that this level of fine is still the exception rather than the rule, but it remains to be seen whether September 2016 represents a step-change in the level of fines for VLOs, or an unusual month with two large fines in the space of a week, skewing the statistics.

The table below tracks the average health and safety fine imposed on corporates only in each month since the Guideline became effective February to September 2016, excluding food hygiene cases.

The health and safety offences charged over the past eight months have covered a range of breaches, both regulatory and statutory. Predictably, there have been more convictions for a breach of section 2 HSWA (67 in total) than any other offence, followed by 32 convictions for a breach of section 3.

Section 2 concerns the duty on employers to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees. Section 3 concerns the duty to persons other than employees, to conduct business in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that they are not exposed to risks to health and safety. The section 2 and 3 charges are notoriously difficult to defend not just because of the broad and subjective nature of the offences but because section 40 HSWA reverses the burden of proof so that where there is a duty to do something as far as is reasonably practicable, it is "for the accused to prove...that it was not practicable...to do more than was in fact done to satisfy the duty or requirement".

Breaking down prosecution by sector

Breaking down these tracked convictions by sector, the high risk industries are: construction and construction materials (accounting for 57 of the 222 tracked convictions); manufacturing (36 convictions); gas, water and multi utilities (15), and general industrials (10). Convictions in the past eight months in other sectors are all in single figures.

It is worth noting the number of prosecutions of individuals for whom, post Guideline, there are much higher risks of imprisonment as a penalty in addition to or in lieu of a fine. Of the 222 convictions reviewed, 61 are of individuals. Many of these of course are sole trader businesses prosecuted for breaches of regulations, or sections 2 or 3 of the HSWA. These have however included two section 7 HSWA convictions, one section 37 conviction and four gross negligence manslaughter convictions. It is difficult to obtain comparative figures pre Guideline because it is only the HSE Prosecutions Area that lists its prosecutions. The Local Authorities are also key prosecutors of health and safety offences and the Police prosecute the gross negligence manslaughter charges. It is worth keeping this under review to see if there is an upward trend.

Section 7 requires all employees to take reasonable care for their own health and safety and for the health and safety of others who may be affected by their acts or omissions.

Section 37 is an offence committed when a corporate health and safety offence is found to have been committed with the, "consent or connivance of, or to have been attributable to any neglect on the part of, any director, manager, secretary or other similar officer of the body corporate."

Mitigation and Aggravating features

The biggest downward impact on fines has always been and remains likely to be the discount for an early guilty plea provided for under section 144 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003. This requires the Court determining sentence, where an offender has pleaded guilty, to take into account the stage in the proceedings at which the offender indicated its intention to plead guilty, and the circumstances in which this indication was given. Under the Reduction in Sentence for a Guilty Plea Guideline, the discount to a fine should generally be one third where the guilty plea indication was provided at the first reasonable opportunity (normally at first court appearance). This discount may be reduced to 20% where prosecution evidence is overwhelming, or more where the plea indication was given at a later stage but before trial.

The biggest expected upward impact on fine under the Sentencing Guideline was the requirement imposed by the Guidelines that, "The fine must be sufficiently substantial to have a real economic impact which will bring home to both management and shareholders the need to comply with health and safety legislation." This could apply to very profitable smaller businesses as well as to the VLOs. In practice, though, while this is often referred to in published Sentencing Remarks, there is not as yet any compelling evidence that turnover size or profitability has so far pushed fines up the culpability/harm brackets in practice at all.

On the contrary

Sentencing Remarks so far suggest instead that mitigating factors have justified keeping a fine within the large company bracket, or that aggravating factors (not turnover) have justified an increase. Notwithstanding the Network Rail and Alton Towers cases, with fines of £4 million and £5 million respectively, no case has yet been sentenced above the recommended large organisation category range of £10 million.

The Travis Perkins case

In the Travis Perkins case which was sentenced in April 2016, a fatal accident had occurred in 2012 when a customer was loading planks of timber onto the roof rack of his vehicle. One of his straps, being used to secure the timber, snapped and he fell backwards and under the moving rear wheels of a slow moving flatbed truck which was in the process of parking beside him. At the time of the accident the yard was, due to an oversight, in breach of planning permission as a consequence of which the parking bays were closer together than they would otherwise have been. The risk of a fall during loading was well known and it was found that there ought to have been an effective traffic management system and a banksman in place.

The Judge suggested that a large number of workers and customers were exposed to risk of serious harm on a daily basis and that these failures were a significant contribution to the accident that occurred. He observed that the planning permission breach was, "somewhat akin to breach of court order" and found that a similar accident eight years before this accident was also relevant.

However, the mitigation which persuaded the Court that even though the defedant was a VLO, the fine should remain in the medium culpability harm category 1 bracket for a large company (fine range £800k to £3.25m) was:

- The fact the company had put a high value on training of its staff and health and safety training specifically. (The HSE accepted this and agreed with the defence that this took culpability down from high to medium).

- The changes made post accident to

prevent recurrence. This included:

- increased signage;

- the introduction of barriers to cordon off loading;

- an improved system of supervision;

- all teams receiving banksman training;

- the offer of podium steps to customers to assist with loading; and

- keeping hatched loading areas clear for loading and unloading.

The Judge said, "Even though this is a very large organisation the mitigating factors here mean that I need not go outside the range in the Sentencing Guidelines for large organisations in the medium culpability, harm category 1 division". However, "size, assets and profit" put the fine near the top end of the range (£3 million), before the reduction for early guilty plea which took the fine down to £2 million.

The Alton Towers and Network Rail cases

By contrast, we have the Alton Towers and Network Rail convictions in September 2016.

In the Network Rail case, sentenced on 21 September 2016, a pedestrian was killed when hit by a train when crossing the line at a level crossing. Because of the speed of approaching trains, pedestrians had a five second visual warning of an approaching train.

A temporary speed limit had been suggested previously to improve safety following previous warnings about the safety of this crossing, but this had not been actioned, nor were warning sirens implemented after they were recommended for the crossing in 2006 and 2008. There were also relevant previous convictions which in particular were taken into account as an aggravating feature. Network Rail's actions post-accident were accepted as mitigating circumstances. A speed limit was immediately imposed and the executive directors turned down bonuses so the money could be used to fund safety improvements. Since 2010, £100 million had been allocated to improve level crossings across the country.

The Judge treated this matter as high culpability harm category 1 (£1.5 million to £6 million guideline fine) and put the fine at the top end of this bracket at £6 million because of: the death caused; the large numbers of the public put at risk; and the aggravating features. This fine was then discounted to £4 million by reason of the early guilty plea. Given that National Rail is a VLO, the Judge considered but did not feel that it was necessary to elevate the sentencing bracket, particularly because of the demonstrable learning of lessons.

In the Alton Towers case, sentenced the following week on 27 September 2016 by His Honour Judge Michael Chambers QC, 16 members of the public (mainly young people and four under 20 years) suffered life changing injuries (but no fatalities) in an accident on the 14 loop 1170m long Smiler rollercoaster. The train they were in collided with a test carriage on the track, when visiting Alton Towers on 2 June 2015.

It had been a windy day – not outside the recommended operating parameters for the roller coaster, and not unusual in the UK, but nevertheless relevant to what occurred. The Smiler was capable of having five trains running at the same time, each carrying up to 16 passengers. Four were running when a problem occurred and the engineers were called out.

The risk of the trains running into each other on the ride is managed by a Programmable Logic Controller ("PLC"). The track is divided into blocks and the PLC monitors each train from block to block. It will initiate a block stop which prevents a train continuing if there is another train in the next block. In the event of a fault, the engineers would put the system into maintenance mode so they could override the block stops and take control, and once the fault had been dealt with they would send an empty train round the track to check it was clear before resetting it to normal.

When a problem occurred the engineers attended and overrode the block stop to fix the issue. An empty train was then sent round the track to test it and a fifth passenger train was added. Probably because of the wind, the empty train was unable to complete one of the loops. That train was manually moved out of the way and a second empty train sent round as a test. This also failed to complete a loop again, probably because of the wind, only this time when it rolled back into the valley of the "Cobra Roll", its presence on the track went unnoticed. Possibly because of the fifth passenger train added, and in spite of the ability to view the track on CCTV, the empty train remaining on the track went unnoticed.

When the ride resumed and the PLC stopped the first passenger carriage, it was assumed this was because of the previous empty train that had been manually removed. No check was made on the CCTV. The system was overridden and the train crashed into the empty train at a speed described as akin to a 1.5 tonne family car colliding at 90mph. Merlin Entertainments, perhaps understandably in these circumstances, initially described the accident as one of human error. They received some criticism for not immediately recognising this as an error in their systems.

The Judge considered that there were some serious aggravating factors - not just the 17 minutes it took to make a 999 call post accident but also: "the lack of proper emergency access to the accident site which meant that those injured remained trapped in great pain and distress hanging at an angle of 45 degrees some 20 feet above the ground for 4-5 hours before being released by the emergency services and taken to hospital". It weighed heavily with him, rightly I think, that those injured were predominantly young people, and also the fact that there was not one collision but twelve, as the two trains crashed and swung back up the loop and back down and into each again in a pendulum effect.

The Judge said, "The obvious shambles of what occurred involving lack of communication and double checking, could and should have easily been avoided by a written system of working to cover [the] crucial period of human intervention including a single overall supervisor and a structured approach to ensuring the track was safe for passengers before authorising a reset and return to normal mode." Other aggravating features noted were a conviction three years before the accident for an incident at Warwick Castle, which also involved a failure to carry out a risk assessment, even though the circumstances of that accident were acknowledged to be very different.

In the Alton Towers case, the prosecution felt that culpability fell into the "high" category. The defence argued that it was borderline high/medium but the Judge concluded that the company: "fell far short of the appropriate standard by firstly, failing to put in place measures that are recognised standards in the industry, and secondly allowing breaches to subsist over a long period of time".

Although the issue was one that existed only on that day, both the Judge and prosecution felt that the system lacking put thousands at risk from the time that the Smiler had opened two years previously. I think that is a particularly harsh conclusion but, as a result, although culpability was initially considered to be in the high category, the Judge elevated it to the "very high culpability" bracket. The risks created, less contentiously I think, were put in harm category 1, notwithstanding defence arguments that the resetting of systems that created the risk on the day was a rare event.

High culpability harm category 1 would have put this case in a sentencing bracket of £1.5 million to £6 million. The elevation to the "very high culpability" bracket pushed the suggested fine range up to £2.6 million - £10 million. While this jump in bracket was made in the context of a review to ensure that the fine based on turnover was proportionate to the overall financial means of the defendant the Judge said that:

It was therefore stated to be entirely by reason of the aggravating features that the Judge moved the matter up a culpability bracket. His judgment was to impose a fine of £7.5 million, reduced by one third to reflect the early plea of guilty, to £5 million.

So what does the future hold?

The health and safety cases sentenced under the Guideline so far have not required the Court to consider a VLO where initial analysis put it in the "Very High" culpability bracket, "Harm Level 1". I would expect such cases to be rare given that very high culpability requires a "deliberate breach of or flagrant disregard for the law". It would be unusual for a VLO not to have health and safety managers in place tasked with ensuring that risks are identified and managed through systems and processes.

In the Alton Towers case, aggravating factors did push the case up from an initial assessment of high culpability to the very high bracket. I feel that was a harsh decision and possibly out of step with previous sentencing decisions. Nevertheless, this decision means it was the first VLO to receive a fine from the highest bracket for large organisations.

Insofar as it is possible for VLOs at this stage to learn lessons from the experience of the first eight months of application of the Guideline:

- Good pre accident mitigation is critical. Make sure that you are doing what you can to identify and minimise risks created by and inherent in all aspects of your business. That includes checking and auditing compliance. Repeatedly. In the event of an accident this will help to keep culpability down to medium or even low fine sentencing brackets. Risks to members of the public need particularly close scrutiny and a high level of vigilance and control to prevent harm.

- Post accident mitigation is also critical. How you remedy an issue and deal with those injured may keep you in a lower sentencing bracket, or conversely, when handled badly, push you up a sentencing bracket. Although Merlin Attractions seemed to be very effective in managing its position post accident with a swift public apology, early acceptance of responsibility and support for those injured, the Judge was critical of the fact that they publicly attributed cause to human error initially, rather than to what was described as a, "catastrophic failure to assess risk and have a structured system of work."

In none of the cases reviewed has a VLO's turnover been the reason why a case has been pushed up a sentencing bracket, nor have any yet been sentenced outside the large organisation table. Although this power hasn't currently been exercised though, the power to elevate a penalty simply because an organisation has a turnover significantly over £50 million annually is there, and with the recent higher fines, it may only be a matter of time before that judicial muscle is exercised.

A downward review of the penalties suggested by the Guideline is unlikely. From the 222 fines for health and safety offences reviewed, the Government has netted £49,578,245.00 which, to give this a context, is the equivalent of the basic annual salary (without expenses) of 661 MPs. Any government will be reluctant to give up this income stream.

It will be interesting to see whether year end statistics demonstrate that the higher fines received under the Sentencing Guideline have in fact had any impact at all on accident numbers. Although punishment is part of the driver for the higher fines, deterrence was also a key objective.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.