1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Sub-Saharan Africa is primed for an era of sustainable growth. As other markets across Latin America and Asia face short-term challenges and many advanced economies decelerate, the outlook remains encouraging for sub-Saharan Africa to gather speed and create greater opportunities for its rapidly growing population.

The region already boasts a strong base in mining, agriculture, and oil production. A growing pool of young and well-educated people is poised to enter the workforce. Investments in infrastructure and the wider adoption of new technologies—such as mobile telephony and Internet services—have the potential to accelerate the growth of a consumer- and service-led economy, as well as cutting-edge industry.

The pace of growth in sub-Saharan Africa could easily surpass most regions of the world

To be sure, the region faces significant challenges. Even as democracy spreads across the region, logistical bottlenecks, poor governance, the threats of increased terrorism and social unrest from rising urban unemployment, and vulnerability to commodity price shocks (with knock-on impacts to macroeconomic stability) and economic downturns in key trading partners indicate the risks to the region's rapid and ongoing transformation. The 2015 Social Progress Index disclosed that the region still scored lower than any other in guaranteeing human well-being.1

As the region moves beyond its colonial past and its traditional reliance on agriculture and extractive industries to integrate deeper into the global economy, key industries will drive a wave of growth in Africa. By increasing the full range of manufacturing activities from low- to high-tech, expanding the penetration of financial services, and focusing on growth sectors like tourism, information technology, and communications, longer-term growth can be realized.

Strong government policies and effective implementation, robust business and infrastructure environment, and a focus on ensuring citizens' basic human needs, conditions for opportunity, and human rights, would drive further stability and growth.

This report will examine the industries with the potential to fuel growth and development over the next two decades for three of the region's most important economies and regional hubs: South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya. While some countries in the subcontinent may actually experience stronger long-term growth, these three key economies together depict the nascent opportunities emerging across much of Africa. In addition, the transitions taking place in Nigeria and Kenya serve as an intriguing counterpoint to those facing South Africa. This report will also examine the public policy considerations and challenges the region's governments must address in order for the region to fully realize its sustainable growth potential.

2. INTRODUCTION AND REGIONAL ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

Beneath recent headlines highlighting sectarian violence, tribal politics, and regional threats of terrorism, a number of promising signs across sub-Saharan Africa are visible. A peaceful and democratic transition in Nigeria suggests that a campaign to root out corruption and more fully share economic gains enjoys wide public—as well as investor—support. Agricultural innovations, a move to higher-value exports, major infrastructure projects, and the increasing use of mobile technologies to boost trade and commerce, are helping to improve the outlook in Kenya, as is the potential for major oil and gas development. In South Africa, the government has clearly acknowledged a need for greater and more coordinated investments in infrastructure, education, and electricity to help strengthen its role as a major trading partner and investor in intra-African trade. Moreover, the "re-basing" and better management of the national accounts of Nigeria and Kenya make their economies far more significant than outsiders might previously have understood.

A diversified economic base offers the region more resilience and less vulnerability to the volatile swings of commodity prices. The rise of a consuming middle class is already boosting the rapid development of its key urban centers. Cities such as Lagos and Johannesburg have become regional hubs for financial services, tourism, and intra-African trade. As incomes rise and new technologies generate new opportunities, a technology-savvy, brand-aware, and sophisticated middle class will attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in sectors ranging from financial services to telecommunications to construction.2

Moreover, rising flows of FDI can help place those institutional forces that promote social progress on a firmer footing. By expanding beyond mere economic priorities to ensure that its citizens have the preconditions for fuller economic participation—improved health, safety, nutrition, and education, as well as personal rights and freedoms—the region can also more rapidly improve the lives of its people.

Since the turn of the new century, the People's Republic of China has taken very intensive steps to strengthen its trade and economic relationships across the subcontinent. One comprehensive survey found some $75 billion in unrecorded development projects between 2000 and 2011—in addition to an estimated $6.3 billion in aid flows each year. The money ranges from direct grants funding projects from dams and railroads to deals to finance and support natural resource exploration.3 Many of these investments come from state-owned Chinese enterprises, who can use subsidized credit to out-bid potential competitors, whether other foreign investors or domestic African firms.

While some critics have suggested Chinese firms invest only to exploit natural resources and cement political connections, many Africa leaders welcome the opportunity for these investments to create more jobs and economic opportunities for their people. Indeed, the rising presence of Chinese investment in Africa helped encourage the Obama administration to announce in 2014 some $33 billion in new commitments to invest in Africa on the part of U.S. private sector firms like General Electric and Coca-Cola.

The economic output of the sub-Saharan region is projected to grow at a 5 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the next two decades.4 As Figure 1 illustrates, while South Africa—the region's most mature economy—will expand by almost 3 percent per year over the next five years, Kenya and Nigeria will grow at rates exceeding 5 percent. Indeed, growth across sub-Saharan Africa over the next two decades could surpass most regions of the world.

3. SOUTH AFRICA: THE CONTINENT'S SPECIAL CASE

Since the end of colonialism and the demise of apartheid in 1994, South Africa has taken enormous strides toward developing into a region of promise. After two full decades of democracy, the living standards of the average South African have risen substantially, with growth exceeding 1.5 percent per year. While the nation's inequality levels remain high, and access to basic nutrition and health must still improve, South Africa has developed more opportunities to create an inclusive society and vastly expanded political choices for its people—all important metrics of social progress.5

"Too few South Africans work, the quality of school

education for the majority is of poor quality, and our state lacks

capacity in critical areas."

– Trevor Manuel, Chairman of South Africa's National

Planning Commission

The nation's competitive advantages have also made it a major destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), and its well-developed logistics and financial services sectors have made South Africa a relatively easy country with which to do business.6 For many foreign firms, it remains the "jumping off" point for developing a comprehensive portfolio of business investments across the African continent and a fulcrum for pan-African trade. Boosting such intra-African trade will be crucial for future prosperity, even as it is likely to face new competition from nations like Kenya and Nigeria.

Yet, stubbornly, South Africa has also failed to grow as robustly as many of its African neighbors. Unemployment, a high level of inequality and continuing labor strife have diminished growth. Infrastructure bottlenecks, especially around electricity generation, have reduced opportunities and diminished productivity. Moreover, the country today faces fiscal and current account deficits that cast a shadow over its economic potential and its ability to withstand future shocks. As the chairman of South Africa's National Planning Commission, Trevor A. Manuel, has written: "Too few South Africans work, the quality of school education for the majority is of poor quality, and our state lacks capacity in critical areas. Despite significant progress, our country remains divided, with opportunities still shaped by the legacy of apartheid."7

Indeed, the long period of racial separation and international sanctions helps explain some of the unique circumstances that distinguish South Africa's long-term outlook from those of Nigeria and Kenya. For example:

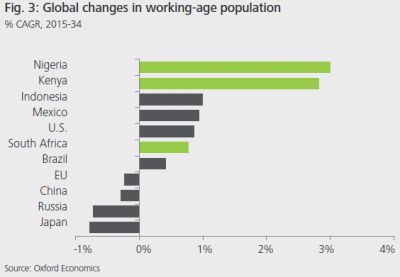

- While the African continent is relatively young and ready to reap a significant "demographic dividend" as young workers enter the labor force, South Africa is relatively more mature—and thus its birthrate is slowing. South Africa's working age population is forecast to grow at just 0.8 percent over the next two decades, a significant slowdown from the 2 percent annual growth recorded over the past quarter century.

- Most other economies in sub-Saharan Africa are deeply involved in agriculture, but food production accounts for just 2.5 percent of South Africa's total GDP, while services account for almost 70 percent of total output.

- South Africa's GDP, now estimated at roughly USD$6,500 per person, makes it appear, from a standpoint of economic development, to be more on par with a rapidly industrializing China than the other, less developed economies of the subcontinent like Kenya or Nigeria, whose vast populations are still transitioning from farm to factory and creating new cities.

Viewed from this distinct structural perspective, the productivity challenges the South African economy confronts today more resemble those faced by an aging Italy or Spain than those encountered by Nigeria or Kenya, where the industrial transformation is ongoing.

In the short term, the South African economy faces significant economic challenges. Growth will be less vigorous than in other parts of the region, falling to only 1.5 percent in 2015, because of relatively high unemployment, labor unrest, and debilitating brownouts and power shortages that deter manufacturing. In a continent beset by poverty and strife, recent xenophobic attacks in South Africa against immigrant populations could deter additional foreign investment and dampen one of the country's chief avenues for potential growth opportunities—its ability to manage foreign involvement in the rest of the subcontinent and inter-regional trade.

From a medium (five-year) and longer (20-year) horizon, however, South Africa's prospects are far more favorable. GDP growth is forecast to rise to 4 percent by 2020 and average 3.4 percent for the next 15 years. The country stands to gain from the strong growth expected in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, where it remains a key investor and intermediary. If it addresses critical infrastructure, the well-being and opportunity of its citizens and other needs, it can become an important player in the medium- and high-value supply chains that will grow up across the region as the rest of the continent industrializes. As regional economies grow, South Africa should attract more tourists and business services.

Unquestionably measures to reduce inequality, expand national infrastructure in a phased and comprehensive fashion, and boost employment will depend on the government's success at implementing the vast majority of structural reforms outlined in the National Development Plan (NDP). The government has estimated that the economy could grow by as much as 5.4 percent per year if it is able to successfully implement the program. While this may be somewhat optimistic, it clearly suggests the sort of opportunities available to South Africa if it can fully carry out its ambitious reforms.

To read this Report in full, please click here.

Footnotes

1. Social Progress Index 2015, Michael E. Porter and Scott Stern with Michael Green

2. "Foreign Direct Investment and Inclusive Growth: The impacts on social progress," Deloitte, http://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/fdi-and-inclusive-growth.html

3. Center for Global Development, Working Paper 323, "China's Development Finance to Africa", http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/chinese-development-finance-africa_0.pdf

4. According to Oxford Economics' forecasts

6. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2014-15.pdf, page 14

7. Government of South Africa, National Development Plan, 2030: Our Future: Make it work

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.